The time-window of the Bengal renaissance was rather small compared to the time-scale of the history of India ~ but within that period, many pioneering great leaders in almost all spheres of human endeavour appeared; in literature, art, science, philosophy, history; especially politics of the struggle for a free India. They all nurtured an incredible spirit of nationalism, “Yes, we shall do it in our land”, yet imbibing the spirit of the West’s best traditions.

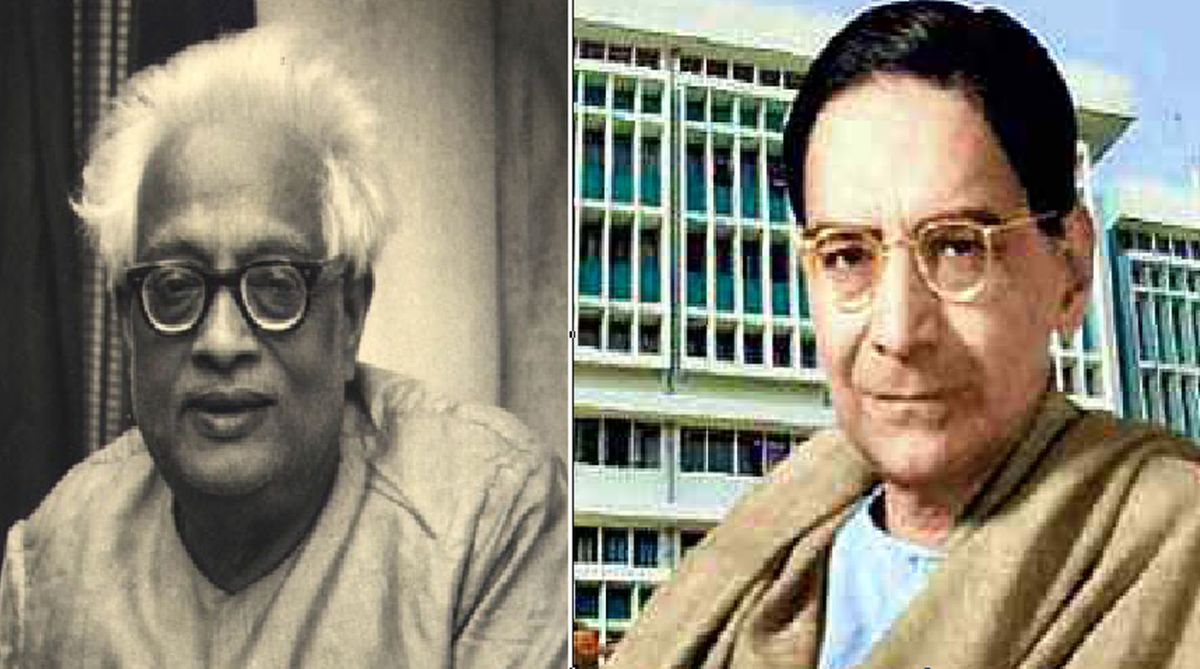

Presidency College in some sense was the cradle of that militant excellence, and the 1920s in particular was a glorious period. I present brief sketches of two stars of Physics at Presidency College, Satyendra Nath Bose and Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, from a personal perspective since their biographies are already well documented.

Advertisement

I met first Bose at Kandi, Murshidabad when he came to inaugurate the Vigyan Bhavan of the local school. I met Mahalanobis later, while on vacation from King’s College, London where I was researching on Nuclear Physics. The two were contemporaries at Presidency College. Subhas Chandra Bose was younger by two years, while Meghnad Saha was their friend and contemporary.

Both were experts in statistics; Mahalanobis famous for his analysis of large-scale statistical survey and D2 theory, usually called Mahalanobis distribution, while Bose became famous for pioneering work in quantum statistics and its application to photons, the light particle, eventually leading to Bose-Einstein statistics. The fundamental particles with a quantum spin of zero or one obey Bose statistics and now known as Bosons. Photons, thus, is a boson. Bose-Einstein condensate was predicted by Einstein using Bose – Einstein statistics.

The greatest tribute to Mahalanobis is the fact that the institute he created is still vibrating with intellectual excellence. He was the first to put India on the world map of statistics. The Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) was more than just an institute for statistics; the continuous traffic of artists, dramatists, physicists, even politicians, made it exciting and vibrant.

Rabindranath Tagore himself was a frequent visitor. Along with Victoria Memorial, the Indian Museum and the Botanical Gardens, ISI was unique. Mahalanobis’ foresight was demonstrated by his passion for computers; scientists from TIFR and Atomic Energy institutions used to visit ISI. Machine intelligence and pattern recognition are still pursued at ISI.

Mahalanobis’ ancestors came from Bikrampur, now in Bangladesh, a zamindar family of landholders. Like Bose he was a product of cultured Bengali, highly enlightened, belonging to Brahmo Samaj, and three generations of kinship with the Tagores.

While courting Rani, he came across her father Heramba Chandra Maitra, the man famous for his utterings Jani Kintu Balbana, to a young man. His deep attachment to Kanan Devi, heartthrob of the Bengali film world and wife of Rani’s brother, was a sensation relentlessly pursued by scandal mongers of Calcutta, but there was no scandal because it was all in the open.

I had the wish of contacting Mahalanobis and I wrote to him before phoning. I heard that famous voice speaking in classical Bengali, without a word of English. He invited me for lunch at Amrapali, which cast a spell; it was so beautifully and incredibly Rabindrik; the furniture, the ambience overwhelmingly reminded me of Gurudev. We went for lunch.

Rani Mahalanobis was charming, and I noticed my young age did not matter to them. The table was a combination of east and west, an arrangement one comes across at Ratan Kuthi in Santiniketan. They ate with knife and a fork. An extremely frugal eater, Mahalanobis finished lunch with long gaps used for conversation. They asked me what I was doing at King’s.

I explained I was teaching and researching in Nuclear Physics. He suggested that when I returned to India, I should join ISI which took me aback. Rani Mahalanobis came into the study and said in charming crystal-clear Bengali, Jano Bikash, Kabi Amake Geon Meye Bolten, Dupure Bhos Bhos Kore Ghumai Bole. Then she left explaining that is exactly what she is going to do.

One morning at King’s I was told that an Indian professor, staying at the Royal Society premises, wanted to see me. Indeed it was Mahalanobis with Rani Mahalanobis; in Bengali he said: “Let’s wait for a while and after that we shall go to Oxford Street”. Oxford Street is full of shoppers; what was Mahalanobis going to do there? He was dressed in an old but splendid tweed jacket, waist coat and grey trousers, with a gold-chain watch in waist coat pocket, a perfect example of a nineteenth-century English professor.

The address was in Oxford Street but of an optician. We went up two floors and a young girl asked “What’s your name, Sir ?” “Mahalanobis”. “Excuse me, I don’t understand.” In my non-statistical mind I asked the woman for a piece of paper and wrote down the name. “Oh! Ma-ha-lo-no-bis?” He was still adamant; “No, it’s Mahalanobis” ~ and so on it went.

As soon as we got back at Oxford Street, he spotted a black cab on the other side of the road, put his hand up and yelled at the top of his voice “Ta-xi-xi”. Oxford Street came to a halt, including the taxi. When we came back to the Royal Society, Rani was negotiating for some mustard oil. It was very touching; a Bengali touch in London.

In 1972, I visited Bombay and while travelling by BARC bus to Trombay, I read in the newspaper that Professor Mahalanobis was no more. He died a day before reaching 79 years in a Kolkata nursing home. The life of a grand man, exuberant, indomitable institution builder, outstanding leader, had ended. With that, my prospect of going to ISI also came to an end.

(To be concluded)

The writer is INSA Honorary Scientist, former Homi Bhabha Professor, Department of Atomic Energy.