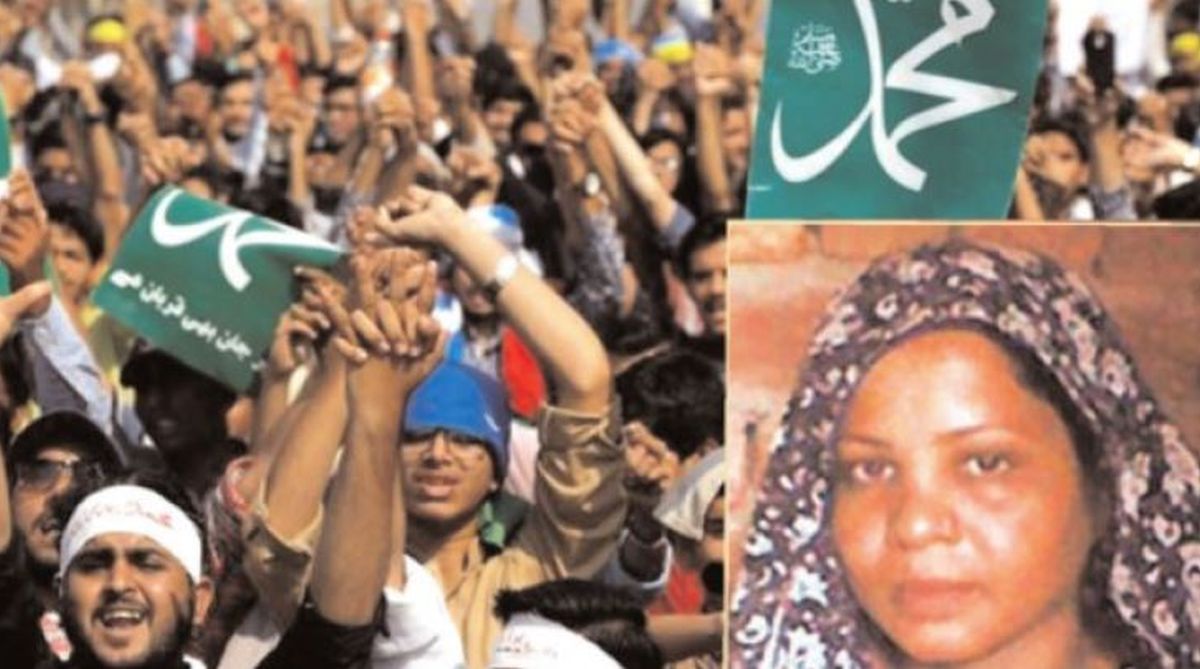

Serious agitations and mob violence have convulsed Pakistan over the acquittal of a Christian woman named Asia Bibi by the country’s Supreme Court. She had been convicted under the notorious blasphemy laws, for which the accused can even be awarded the death sentence.

Pakistan’s penal code prohibits blasphemy against any recognised religion. During the1980s, blasphemy laws were extended by the military government of General Ziaul- Haq. From 1967 to 2004, over 1,300 people have been charged with blasphemy. A large number of the accused have been murdered before the conclusion of their trials.

Advertisement

The opponents of blasphemy laws have had to face the angst of the die-hard Islamists. Salman Taseer, former Governor of Punjab, who had raised his voice against blasphemy, was shot dead by one of his bodyguards. Critics justifiably complain that Pakistan’s blasphemy laws target and persecute the minorities.

However, any amendment to the laws has been stoutly opposed by the Islamic parties. On 7 September 1974, under Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s patronage, Ahmadi Muslims were declared as non- Muslims. This was supplemented by new blasphemy provisions in 1986 and these applied to Ahmadi Muslims.

More than 96 per cent of Pakistanis are Muslims. Among the predominantly Muslim countries, Pakistan has the strictest blasphemy laws. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) has documented such cases. It states that Muslims constitute the majority of those booked under the blasphemy laws, closely followed by Ahmedis.

The laws have openly been misused to settle personal scores, and have nothing to do with religion. Mere accusation of blasphemy is enough to make someone an easy target of the hardliners. The Hanafi School of Jurisprudence, on which Pakistan claims to model the legal system, does not mandate death penalty for non-Muslims who insult the Prophet.

It bears recall that President Musharraf had tried to implement the blasphemy laws in a less arbitrary manner. It was jettisoned in the face of protests from pro-Islamic parties. He was also forced to back down on a proposal in 2005 to delete the so-called “religion” column. First introduced in 1972, and subsequently extended by Gen Zia, it singles out Ahmadis as non- Muslims and requires all Pakistani passport-holders to specify their religious affiliations. It erodes the constitutional and legal rights of non-Muslims and renders them vulnerable to discriminatory treatment by the state institutions.

The International Commission of Jurists has observed that Pakistan’s blasphemy laws have been misused. Concern over these draconian laws have been raised by human rights organizations. They contend that Pakistan’s offences against religions violate its obligations under international human rights laws. It has asked Pakistan to review and radically amend the same.

Reactions against the judgment of the Supreme Court have been furious and predictable. Hardcore Islamists have demonstrated in Lahore and other cities, burned vehicles, and threatened the judges who had pronounced the judgment. Out of fear and panic, defence lawyers fled the country. Christian schools in Lahore were closed indefinitely for reasons of safety. The violent movement was spearheaded by a party of hardcore Islamists under the banner of Tahreek-é-Labhalik, which was formed in response to the hanging of the bodyguard, who had killed the Punjab Governor. The founder of the party is a rabid cleric, named Muhammad Azjal Qadri.

The brave stand of the Supreme Court judges was backed by Prime Minister Imran Khan himself. This was remarkable because earlier, during election campaigns, Imran and his party Tehreeq-é-Insaf had proclaimed their support for the blasphemy laws.

Displaying unexpected courage, Imran declared that the Government would crack down on the protesters, and not allow them to destroy public properties with abandon.

Before a face-off with the hardliners, the Prime Minister must have consulted the Army, and obtained assurance of its support. However, events have turned out differently. As the agitation gathered momentum, the government effected a U-turn and agreed to go in for a review of the court’s decision. It released the arrested agitators and put Asia Bibi on the list of people forbidden to leave the country.

This happened mainly because the Army is unwilling to go in for a confrontation with the agitators, who are Barelvis and supposedly more moderate than the Deobandis, from whom the Taliban draws its support. Sunni extremism in Pakistan remains largely associated with the Wahhabis, who dominate terrorist organizations like Lakshkar-é-Taiba, which was responsible for the Mumbai terror attacks, and Deobandi Sunnis, who are associated with the Taliban and its various affiliates.

Barelvis are considered to be more moderate and syncretic than the Wahhabis and Deobandis because of their reverence for Sufis. Now their leader Khadim Hussain Rizvi has opted for a more violent course of action. Earlier, Rizvi had organized protests against changes in Pakistan’s electoral laws, that changed the language of the oath for law-makers.

The change in the wording of the oath was minor. It had substituted the words ‘solemnly swear’ with the word ‘affirm’. Rizvi demands a rigid adherence to blasphemy laws and stricter laws against other religious sects. He considers himself as the guardian of the “Prophet’s honour.”

Pakistan’s military intelligence extended support to this group during the Musharaf years and even later as a moderate alternative to the rabid Wahhabi and Deobandi groups. It is open to question how Imran Khan’s government will countenance the threat posed by Rizvi and his followers, who are quiet for the time being, but will definitely try to stoke violence if the Supreme Court in its review of the case does not reverse its judgment.

It is likely that the Army will broker some sort of a truce between the government and the Islamists. The army is apparently playing on the backfoot because the agitators have arraigned the Army Chief, General Qamar Bajwa, because of pro-Ahmedi leanings. As things stand, there will be no change or dilution of blasphemy laws in Pakistan, and Imran Khan will have to beat a quiet retreat.

The writer, Senior Fellow of the Institute of Social Sciences, had served as Director-General, National Human Rights Commission, and of the National Police Academy.