Delhi CM slams AAP for questioning her govt on the first day

She pointed out that Congress ruled Delhi for 15 years and the AAP over a decade bringing Delhi on a back foot.

Challenges of infrastructure and corruption as experienced in case of RSBY may also confine the success of Ayushman Bharat but it is imperative to look at the positives too

The Prime Minister’s Independence Day speech of 2018 marked the announcement of yet another scheme, this time pertaining to the ailing healthcare situation of India. Ayushman Bharat – National Health Protection Scheme (AB-NHPS), tagged as Modicare is deemed to be one of the largest health insurance schemes in terms of extent and expense. The scheme can be seen as an extension of the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana launched by the UPA government in 2008.

Like RSBY, AB is targeted at poor, deprived rural families and identified occupational category of urban workers’ families. Specifically, according to the Socio-Economic Caste Census (SECC) 2011 data, 8.03 crore families in rural and 2.33 crore in urban areas will be entitled to the benefits of scheme, i.e., it will cover nearly 10 crore people. AB-NHPS offers to provide an insurance cover of Rs 5 lakh per family (on a family-floater basis) per year for secondary and tertiary care hospitalisation marking an overarching increase of 1500 percent in the coverage amount compared to RSBY.

Advertisement

Indeed, as elections approached, addressing the needs of people will be the BJP’s mandate and launching Ayushman Bharat has been labelled as one move in this direction. It cannot be debunked that the scheme may sound impressive but sustaining it financially, with the proposed premium rates, seems almost impossible.

Advertisement

Tracing the inpatient care expenditure from the recent health survey provided by National Sample Survey shows that the nearly Rs 18,500 crore is spent by the bottom two expenditure quintiles in India – the target populace for the scheme – while the premium proposed hovers around Rs 1,082 per household which translates to Rs 10,820 crore implying huge losses for the insurance companies. In fact, given that such a health insurance scheme will reach many marginalised households for the first time, pent-up need and demand for healthcare will in all probability imply high burn-out ratios for the insurance companies making the scheme economically unviable.

AB-NHPS like RSBY is focussed on in-patient care while in India ambulatory or OPD care poses a bigger economic challenge. Such care is frequently needed. A study by Laveesh Bhandari, Peter Barman and Rajeev Ahuja (2010) based on the 2004 health round of the National Sample Survey found that outpatient care has a greater ‘impoverishing effect’ than inpatient care in both urban and rural areas.

The analysis of nationally representative data from India also shows that high out-of-pocket (OOP) payments have pushed 3.5 per cent of the population below the poverty line. However, if OOP payments on either medicines or outpatient care are excluded then only 0.5 per cent falls into poverty due to spending on health. This suggests that insurance schemes that only cover hospitalisation charges would not be very helpful in protecting the poor from impoverishment due to OOP. This requires health schemes to have broader coverage that would include outpatient care as well as drugs.

Ayushman Bharat fails to address this issue. Challenges of infrastructure and corruption as experienced in case of RSBY may also confine the success of AB but it is imperative to look at the positives too.

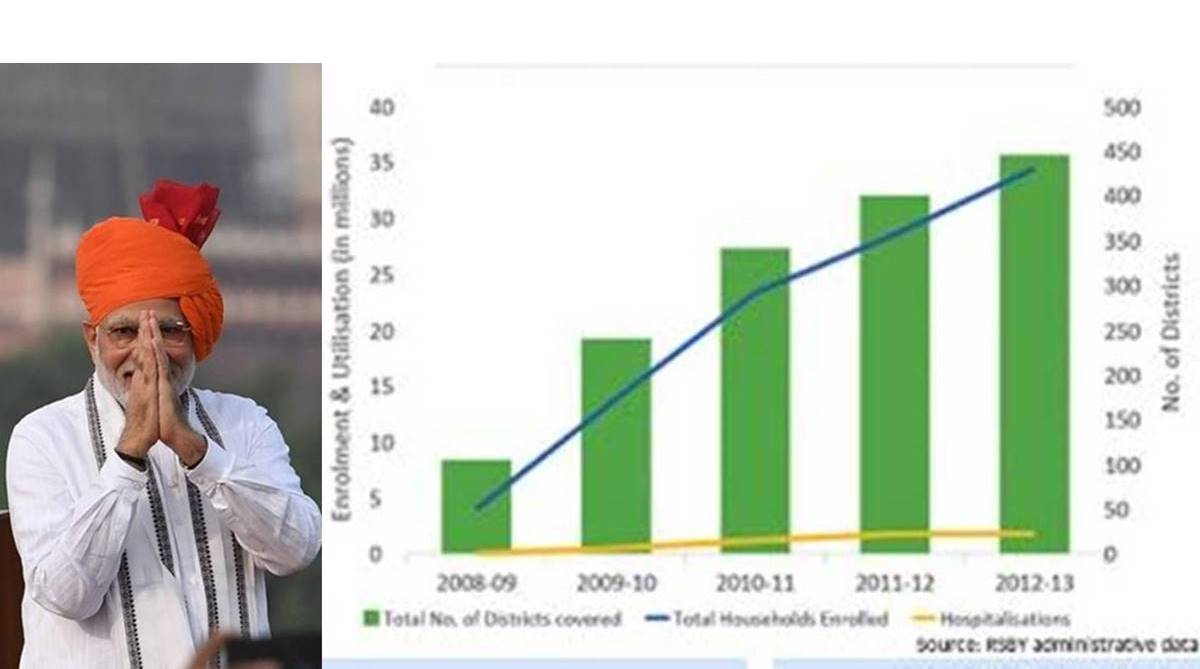

The chart published with this report presents the coverage and utilisation of RSBY since inception and it has improved over the years. Another study by Manchanda and Chaudhary (2016) finds that RSBY, if placed in the larger perspective of providing social security to poor, did fail to cover some of the most backward districts of the country where the proportion of the poor was higher.

Also, they opined that introduction of an insurance programme without proper infrastructure in place like health centres, roads and electricity is redundant for the poor classes even if it reaches such underdeveloped districts as the scheme in such cases merely ensures “availability” without really ensuring accessibility of the health care service.

Despite highlighting the loopholes in the functioning of the RSBY, the authors highlighted the larger picture of poverty and associated insecurity for the majority of the population in India for whom RSBY served as an important policy measure, providing access to inpatient care – to many for the first time! “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step,” saidLao Tzu.

Hence, it is imperative to have a comprehensive health policy in place and then work towards it’s efficient implementation than denouncing it altogether at its infancy.

(The writers are respectively a Ph.D Scholar at Jawaharlal Nehru University and a Research Intern with Outlier Research Solutions)

Advertisement