VBU allows visitors in campus after a gap of five years

After a gap of almost five years, visitors will be allowed to visit the campus of Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan.

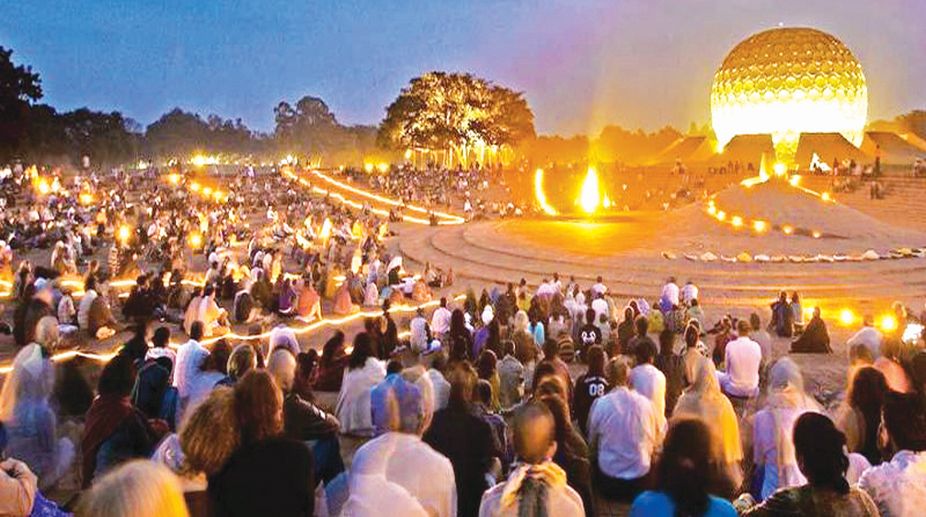

Auroville an experimental community in southern India.

On 28 February 1968, a few thousand people gathered on a barren plateau of red laterite, some ten kilometers north of Pondicherry, the former French establishment. It was a special moment for those present; it was the birth of a ‘Dream’ which had rarely been attempted in the past; to bring people from different countries, races, religions, backgrounds in one single place to build a city together, ‘a Tower of Babel in Reverse’

The person who had this ‘strange’ utopian idea was French-born Mirra Alfassa, known as the Mother, Sri Aurobindo’s collaborator. The most astonishing feature is that the ‘dream’ still exists; it is celebrating its 50th anniversary and the Prime Minister of India acknowledged this remarkable achievement by gracing the occasion with his presence.

Advertisement

The Mother had described her Dream: “There should be somewhere on earth a place which no nation could claim as its own, where all human beings of goodwill who have a sincere aspiration could live freely as citizens of the world and obey one single authority, that of the supreme truth; a place where the needs of the spirit and the concerns for progress would take precedence over the satisfaction of desires and passions, the search for pleasure and material enjoyment.”

Advertisement

More than a utopian concept, it was perhaps a first ‘smart city’.

Reading this Dream again reminded me of a discussion with a group of senior Indian civil servants a couple of years ago; the discussion turned to one of Prime Minister Modi’s flagship schemes, ‘Smart Cities’. After some time, one of the participants dared to ask: “But what is a Smart city?”

One officer answered that it is an important scheme through which the Prime Minister hopes to change India.

Someone else pointed out that this did not really explain what a ‘smart city’ was. Will this change the lives of city dwellers, particularly in places like Delhi or Mumbai, where traffic and pollution is increasing by the day?

A better-connected person admitted that a few weeks earlier, he had phoned one of his colleagues, serving in a senior position in the Ministry of Urban Development and asked the latter the same billon-rupee question. The answer was: “We are not sure as yet, but we are working on it”.

There is no doubt in anybody’s mind that there is urgency for Delhi to become smarter, if something drastic does not take place, millions will soon suffocate under the increased pollution, a total disfunction of communications and more generally, the degradation of the quality of life.

After recently visiting Bhutan, I realised that an important factor had been left out ~ happiness. Should not citizens be happy in their smart city? It seems obvious, except for the ‘planners’! Even if the concept of ‘happiness’ places the bar too high, some well-being of the body and mind should be included in the objectives of the ‘smart cities’.

It is where Auroville has perhaps a role to play, because the human aspect has been central to the development of the ‘universal city’.

In early 1968, as the world was churning (it was three months before the May 1968 students’ revolution in Europe), this utopia began to take shape. Instead of destroying ‘an old world’, the idea was to construct a ‘new’ one; it was undoubtedly far more difficult, because it meant building new men and women. Indeed, this apparently crazy ‘lab’ had all chances to explode apart under the pressure of human egos.

The experiment was to be ‘universal’ in its approach; to symbolize this, young couples representing 121 countries and 23 Indian states placed a handful of soil from their respective countries or states, in a lotus-shaped foundation urn at the centre of the future City. In the midst of the red desert, the banyan tree nearby would become the geographical centre of the City.

From her room in Pondicherry, The Mother solemnly announced: “Greetings from Auroville to all men of goodwill; are invited to Auroville all those who thirst for Progress and aspire to a higher and truer life.” She later read the Charter of Auroville through an All India Radio broadcast, giving, in her frail voice, the first direction to the new project: “Auroville belongs to nobody in particular. Auroville belongs to humanity as a whole. But to live in Auroville, one must be a willing servitor of the Divine Consciousness.”

The fact that it received the unanimous endorsement of the General Assembly of UNESCO did not change much the lives of the pioneers, who had to ‘survive’, often on millet, during the hot summer of South India, living in rudimentary huts.

At first, only a couple of hundreds heard the call, to what the founder called a ‘Great Adventure’. However, after the Mother passed away in November 1973, life changed drastically. The Aurovilians were then left to stand on their own feet, materially and spiritually. But they knew that they had to carry on the mission given to them by their mentor, to built the ‘City that Earth Needs’; a smart city before its time.

The task was immense, but the most immediate need was down-to-earth, to create shade from the scorching sun. In the process, the first Aurovilians had no choice but to become ‘smart’, i.e. by planting forests in the desert, their life became ‘cooler’.

Aurovilians started to rejuvenate the arid land; they planted millions of trees, built bunds and dams to stop the soil being washed away with the monsoon rains and constructed the first primitive houses. It is how the first pioneers became ‘experts’ in environment, giving Auroville the reputed expertise it has today.

The problems began accumulating and with recurrent shortage of funds, the Mother’s words, came back to everybody’s mind: “Auroville wants to be a self-supporting township…” The Dream also said that in Auroville “money would be no longer the Sovereign Lord, individual merit will have a greater importance than the value due to material wealth and social position”; money had nevertheless to be generated for the project to survive and develop. Auroville then became known for its crafts.

I remember that in the early Eighties, very few in India knew about Auroville; the project had the reputation of a place with strange foreigners roaming around. What were foreigners or even Indians doing in this wilderness, when most dreamt of America?

Nobody could have then guessed that just over three decades later, Auroville would be visited by thousands of people every day. Auroville may not yet have succeeded in all its objectives, but the way of life chosen by the pioneers is today acknowledged by many.

The Dream was indeed ‘smart’: “In this place, children would be able to grow and develop integrally without losing contact with their souls; education would be given not for passing examinations or obtaining certificates and posts but to enrich existing faculties and bring forth new ones.

In this place, titles and positions would be replaced by opportunities to serve and organise; the bodily needs of each one would be equally provided for, and intellectual, moral and spiritual superiority would be expressed in the general organisation not by an increase of the pleasures and powers of life but by increased duties and responsibilities.”

All its objectives are far from being realized, but the Dream survives fifty years later; let us hope that the Smart Universal City will slowly continue to take shape.

The writer is an expert on China-Tibet relations and author of Fate of Tibet

Advertisement

After a gap of almost five years, visitors will be allowed to visit the campus of Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan.

The Rajasthan government has taken swift action to boost urban development by incorporating 210 villages in Bharatpur into mainstream urban planning through the newly constituted Bharatpur Development Authority (BDA).

The delegation landed at Jorhat Airport on Monday, setting the stage for a series of engagements aimed at showcasing Assam’s cultural heritage and economic potential.

Advertisement