Art and artist: Siddharth Somaiya on giving voice to the voiceless

In an interaction with The Statesman, the award-winning artist talks about Immerse Fellowship, a pioneering initiative dedicated to empowering emerging Indian artists and curators.

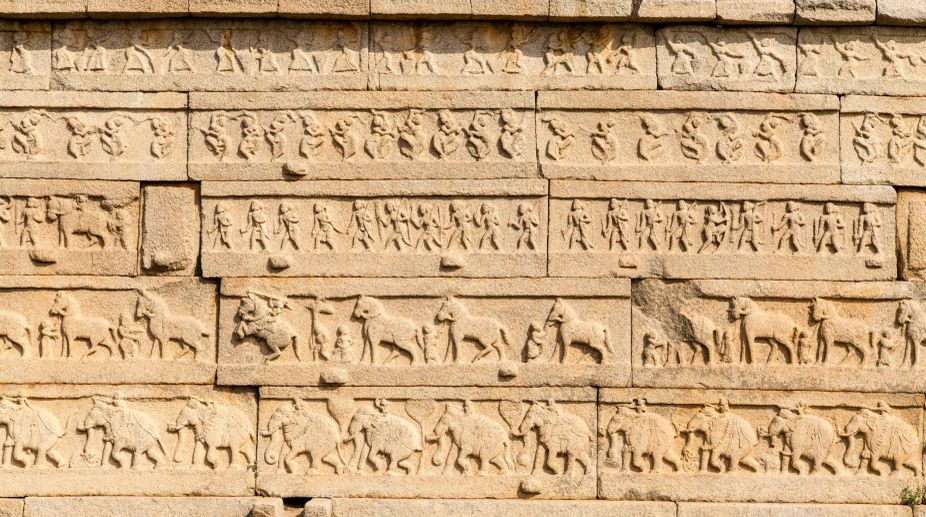

Representational image (Photo: Getty Images)

Early Indian art, like Indian spirituality, is the manifestation of a perception of harmony, of oneness and a serene flow of internal bliss. This realisation is not generated by intellect or intellectual pursuit. In the spiritual sphere, the Vedic Rishi is the seer (drasta) of the eternal truth. The language of the veda is a rhythm, a divine word that vibrated out of the infinite to the inner self of man. It was capable of receiving the throbbings of impersonal knowledge.

Similarly, in the cultural sphere, the art of India showcases a spectacle of one of the most ancient, civilisations of the world. The artist out of introspection, a deep realisation from the heart, undictated and undeterred by intellectual reasoning, finds out the expression straying into his consciousness out of the expansive multifaceted nature, a part of the glowing domain of the Infinite. It is by virtue of its unsullied spontaneity and pristine purity that the images were projected. The worldview envisages a concord in the whole of creation.

Advertisement

It sees the same one that is in each of us ~ the flowers, the trees, the animals and other creatures, the squally wind and gentle breeze that at once appals and soothes. This exalted moment of aesthetic experience is described in Indian philosophy as Bhramananda or ultimate ecstasy of salvation ~ a total self-abnegation and surrender. Indeed, art has played an important role in the life of the subcontinent.

Advertisement

Chitrasutra of Vishnudharmottara Porana, which was composed out of earlier oral traditions in the fifth century AD, is perhaps the oldest treatise on art in the world. It states that art is the greatest treasure of mankind. It is more valuable than fame, pelf or prosperity and pearls and jewels. For about a thousand years in early times, an enormous volume of art was produced in India. This depicted deities, mythical creatures, animals, plants, trees, forms that combined these visuals in remarkable concord, in a harmonious blending of different items and also common men and women. But this art never depicted the kings who patronised it.

Nor was the name of the artist ever mentioned. Like the conception of the Rishis of the Vedic era, this conception of art was also indicative of a revelatory knowledge. Thus, individuals did not matter, it was the expression that mattered. So, it was to a large extent an anonymous creation. According to Chitrasutra, personalities are rather unimportant to be depicted in art. The purpose of art like the aim of an ascetic’s quest is to display the eternal beyond the ephemeral, transcendental beyond the terrestrial, celestial beyond the sublunar.

There are decisive indications in the Indian monuments of a grand, cosmopolitan culture since the earliest times. Influences of art from the Greeks, the Parthinians and from other sources were greeted with considerable warmth, as is evident from Buddhist art and pillars in India. These influences have continued uninterrupted and percolated to the mainstream of art through the centuries.

Artistic styles, designs, motifs and ichnography have been displayed throughout the country since the ancient era. Regional characteristics, local variations and colour enriched these pan-Indian themes further still. It is a disgraceful misfortune that a stupendous mass of the early art has been destroyed by the ravages of time, leaving only an infinitesimal portion thereof.

In the fourth millennium BC, one of the earliest civilisations of the world was developing in the river valleys of the Indian subcontinent following substantial growth and uniform improvement of agriculture. The first sites of these civilisations were discovered in the basin of the Indus river and this has been popularly known as Indus Valley Civilisation.

Excavations across this culture have not revealed evidence of military might or weaponry for warfare. While the art of other civilisations has many images of prisoners, monuments, war-victories and other activities relating to warfare, the art of the Indus Valley Civilization does not boast any such depiction. More than 3000 seals have been recovered through excavations at Indus Valley sites.

Most of these seals combine text with images of animals, plants and persons. They are made of clay, stone or copper and would have been pressed into soft clay to leave their impression. As with any culture, art provides a glimpse of the underlying political, social and religious ethos. Bulls, elephants, bisons, rhinoceros and crocodiles are depicted in a highly naturalistic manner even within the small space of the seals. A highly significant and fascinating seal is the one depicting a hermit ~ a man sitting cross-legged on a seat with splayed arms.

The pasture reminds us of yogic asanas and this art is the invariable symbol of religious asceticism. This depicts renunciation through meditation and concentration. The artefacts that have been excavated from the Indus Valley Civilisation are unique in their small scale. No monumental sculpture has been found. All the art objects whether in terracotta, stone or metal are described as being on a human scale. No palaces or other gigantic specimen of architecture have been discovered. Monumental architecture and art, that displayed regal authority and elegance, followed much later.

The use of a variety of materials was suggestive of the highly impressive level of development of art. The artist was not merely using those materials that were available to him in the area. Specific artistic and aesthetic choices were made and objects wee fashioned from pliant terracotta to hard stone and metal. A variety of styles ranging from the highly naturalistic to abstract and stylised forms such as the figure of a dancing girl with one hand on her hip and similar other stylised figures were found. These works of early art of India were meant to convey the truth as generated by the consciousness of the artist.

The artist claimed that it was he alone who had seen the truth. Every teacher of the ancient period stated that he only followed in the footsteps of others who went before him. The special trait of Indian artists is bereft of ego. Utterly selfless and free from the fetters of ego, the artists reflected the innate spiritual culture of Indian thought and philosophy. It is altruistic in essence. The object that the artist depicts does not have its teeth, nor does it fume with disgust.

Not the scintilla of a frown is discernible on its nature, with a joyous and merry surrender to the natural order without any pugnacious attempt to ride roughshod over the natural forces, inimical or otherwise. For, it is essentially a culture emanating from the belief and perception of an underlying unity of the whole of creation.

(The writer is a retired IAS officer)

Advertisement

In an interaction with The Statesman, the award-winning artist talks about Immerse Fellowship, a pioneering initiative dedicated to empowering emerging Indian artists and curators.

The Progressive Art Gallery in Dubai has set up an exhibition entitled - "Intertwined: Revisitation of the Indian Art Narrative," showcasing the theme of art as protest, especially in the context of contemporary India.

Kolkata’s art landscape recently welcomed a fresh voice with the solo exhibition of an emerging artist, Priyanka Bhattacharjee, titled Rutted Terrain.

Advertisement