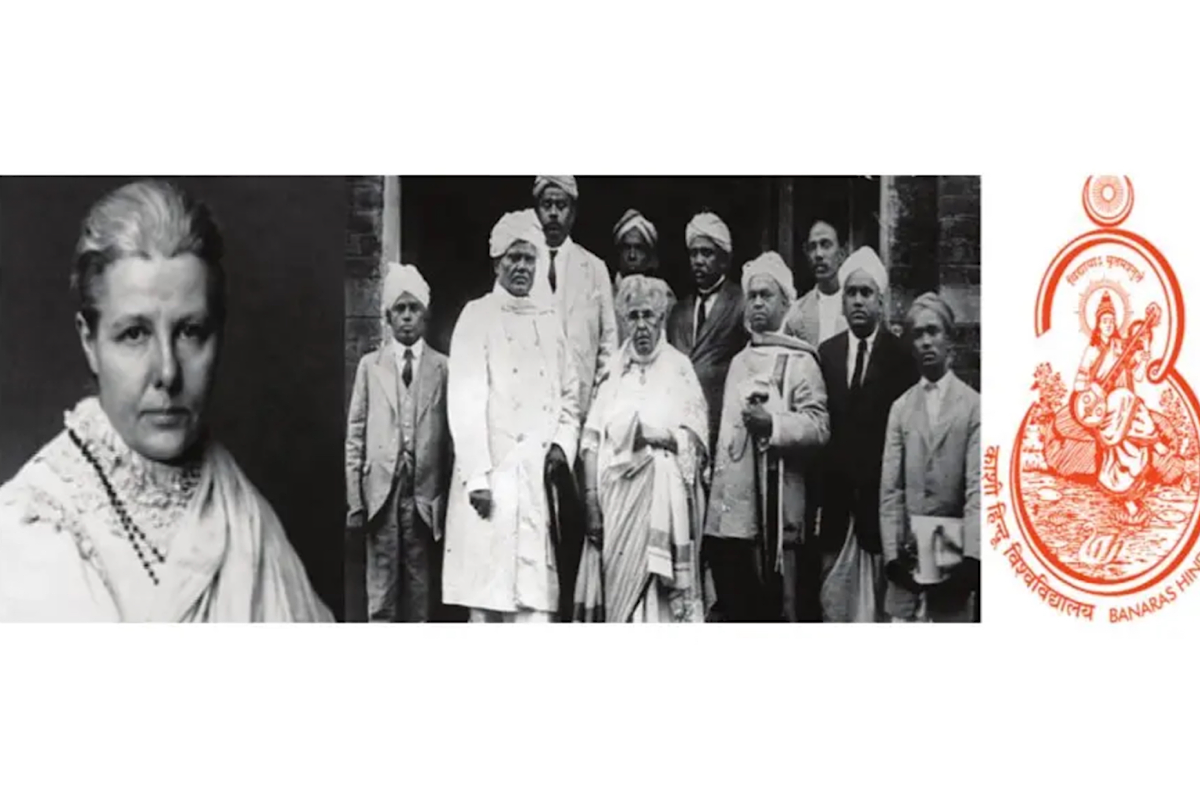

When renowned Sanskrit scholar Pandit Gangadhara Shastri saw Annie Besant welcoming guests at her home ‘Santi Kunj’ in Benares in 1901, he exclaimed (in Sanskrit), “The all-White Saraswati, one of the designations of our Goddess of Culture and Learning.” The athome meeting was ostensibly to renovate an old temple but it was an occasion for Mrs Besant to ‘Indianise’ herself, to get in touch with the hearts of the Indian people; living, looking and speaking just like them. As our globalized world commemorates International Women’s Day, it is an opportunity to delve into to the life, times and works of Annie Besant who travelled from England to land in Kandy, (Ceylon) on 16 November 1883, where she inaugurated her tour with lectures. Subsequently she spoke at Tuticorin, Bangalore, and Bezwada; and there was a great convention held at Adyar, later the chief headquarters of the Theosophical Society, at which she spoke on ‘The Building of the Cosmos’.

During 1894, Mrs Besant lectured successively at Benares, Agra, Lahore, and Bombay, When at Adyar, she threw herself into the work of founding a school for backward communities called Olcott Panchama School and she began her campaign of national education. Even before she landed in 1893, Annie Besant was referring to India as her ‘Motherland’ in letters to associates. She soon became one of the prime movers of the Women’s Indian Association and its first President.

Advertisement

The Association was influential across the country, and its focus was on furthering upliftment of women in education, industry and politics. Having brought urban, educated and politically aware women under one umbrella, the Association made its presence felt when the Southborough Commission visited India. Mrs Besant and Sarojini Naidu, along with other members, presented a memorandum to Lord Montagu, Secretary of State for India, stating Indian women should be made eligible for franchise on the same terms as men. The ‘all-White Saraswati’ was committed to establishing the Central Hindu College at Benares in 1898 with the cooperation of Indian colleagues, only some of whom were theosophists.

She was convinced education in India had to be in hands of Indians, completely controlling the academic, financial, and administrative responsibilities. Moreover, the guiding spirit of Indian education would be patriotic in outlook, dovetailed with spiritual and religious legacies of the land, and with the ability to take utmost advantage of Western science and technology. For students, fees would be minimal; for their intellectual, physical, and emotional growth, she spoke up for Brahmacharya or celibacy for young adults. Religion was made an important plank of education and, in addition, the youth were to be trained for social work. Sure enough her vision for the Central Hindu College got morphed into an even bigger one, when Pt Madan Mohan Malaviya, a great patriot and Congress leader, proposed the formation of the Benares Hindu University (BHU).

The Central Hindu College became the seed from which grew the enormous tree of knowledge and learning, blessed by the sweat and toil of Mrs Besant. When BHU was established in 1916, it marked the culmination of Pt Malaviya’s dream project of bringing together heads of Princely States, wealthy businessmen, landowners, and common people of India to contribute towards the ‘Kashi Hindu Vishwavidyalaya’. Kashi Naresh Prabhu Narayan Singh, Raja Rameshwar Singh, several Maharajas, including the Nizam of Hyderabad and Maharana of Mewar, Udaipur, contributed handsomely to the cause of education, nationalism, and national pride which Pt. Malviya had roused. Today, if BHU remains one of the largest and most influential universities of the world, the ‘all-White Saraswati’ had a critical role to play.

The figure of Goddess Saraswati adorns the crest of BHU. In 1921 the University honoured itself by conferring a doctorate on Annie Besant. Her institution-building aside, Mrs Besant’s writings and lectures covered a spectrum of subjects with religion, philosophy and sacred books engaging her encyclopaedic mind. In December 1905, she delivered four lectures titled ‘Hints on the Study of the Bhagavad-Gita’ at the Theosophical Society at Adyar, Madras. The BhagavadGita or The Lord’s Song was an English translation, with the original text. It was published in 1907, and over 80,000 copies were sold in merely four years. . ‘Hints on the Study of the Bhagavad-Gita’ is a slim, 140- page book with her explanations. “To speak of the Gita is to speak of the history of the world, of its complexity, of the web of desires, thoughts and actions which makes up the evolution of humanity; for the book is not simply the story of the teaching of Arjuna by Shri Krishna – it far more than that. And all that one can pray in taking up a task so far beyond one’s power is that flute, whose music compelled melody even from the very stones that heard it, may breathe the same all-compelling music in the heart of speak and hearers alike; so that out of that music some note may echo in the hearts that are gathered here, to breathe over the lives that spring from those hearts something of the spirit embodied in the Gita words.” The four lectures were designed to make messages from the Gita easier to understand.

She said, “He who can understand the complexity of the Gita can understand likewise the complexity of the world in which the Author of the Gita is the upholding and the sustaining life, and complex as the world is the Gita, both worthy of the profoundest study. But in these modern days the study is a difficult one, for the way of the Divine Teacher is not the way of the human pedagogue. God does not teach as man teaches, in textbooks written for a boy to learn, exercising his memory rather than unfolding his life. Nature, which is the outer reflection of Deity, does not teach us precept by precept, by spoken words easy to understand; so, you notice that in the Gita, where the method of teaching is that of the Divine Teacher and not that of the pedagogue, there is much confusion, much difficulty; and almost vexation shows itself, from time to time, in the heart and even on the lips of the learner.”

Mrs. Besant guided the audience through the maze of confusion: “You must recall shloka after shloka in which the confusion of Arjuna shows itself, sometimes in pleading, sometimes in almost petulant words: ‘I ask Thee which may be the better – that tell me decisively. I am Thy disciple, suppliant to Thee; teach me’. And the answer? A long discourse, eloquent, beautiful, full of profoundest wisdom, but after the discourse, what is the result on the mind of the listened? ‘With these perplexing words Thou has only confused my understanding; therefore, tell me with certainty the one way by which I may reach bliss’.” Sharing one of the key lessons, Mrs. Besant declared, “It is not the Master who refuses the light; it is the disciple who is not able to see by it, to understand. For the pupil is needed as well as the teacher, the receptive mind as well as the wisdom that flows from divine lips. Of what avail the white splendour of the sun, if it falls on eyes that are blind to its radiance?

The difficulty, my brothers, lies with us and not with Those who teach. Now this is the first great lesson of the Gita. That the pupil must make himself. You can learn all the outer things that man can teacher by outer teaching, though even there the power of the pupil must condition the illumination the mind receives, and the instruction to him consists only of that which he assimilates.”

In her second lecture, she enumerated: “The nature of the Gita is in its essence, as a Yoga Shastra, a Scripture of Yoga,” adding, “ Under this will come the question of activity, the nature of activity, its binding force, the method of escape from its bonds by yoga; that will lead us to a consideration of what is meant by yoga; what is meant by the yogi; and, later on, we shall have to ask what means are there within our reach by which yoga may be attained?…

The whole object of everything said and done, as recounted within the covers of the Gita, has but one motive: to give Arjuna heart and courage, to drive him into action, to force him, if need be, into battling; and the argument is continually interspersed with the constant refrain: Therefore fight.” During the height of the Free Thought movement an English poet Gerald Massey, a contemporary of Mrs Besant, penned the tribute: “You for others sow the grain; / Yours the tears of ripening rain; / Theirs the smiling harvest gain. / You have soul enough for seven; / Life enough the earth to leaven; Love enough to create Heaven. / One of God’s own faithful few; Whilst unknowing it are you; Annie Besant, bravely true.”

(The writer is an authorresearcher on history and heritage issues, and former deputy curator of Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya)