US pauses aid to Ukraine, say reports

US President Donald Trump has paused all aid to Ukraine till as much time as it takes to determine President Volodymyr Zelensky's commitment to ending the war with Russia,

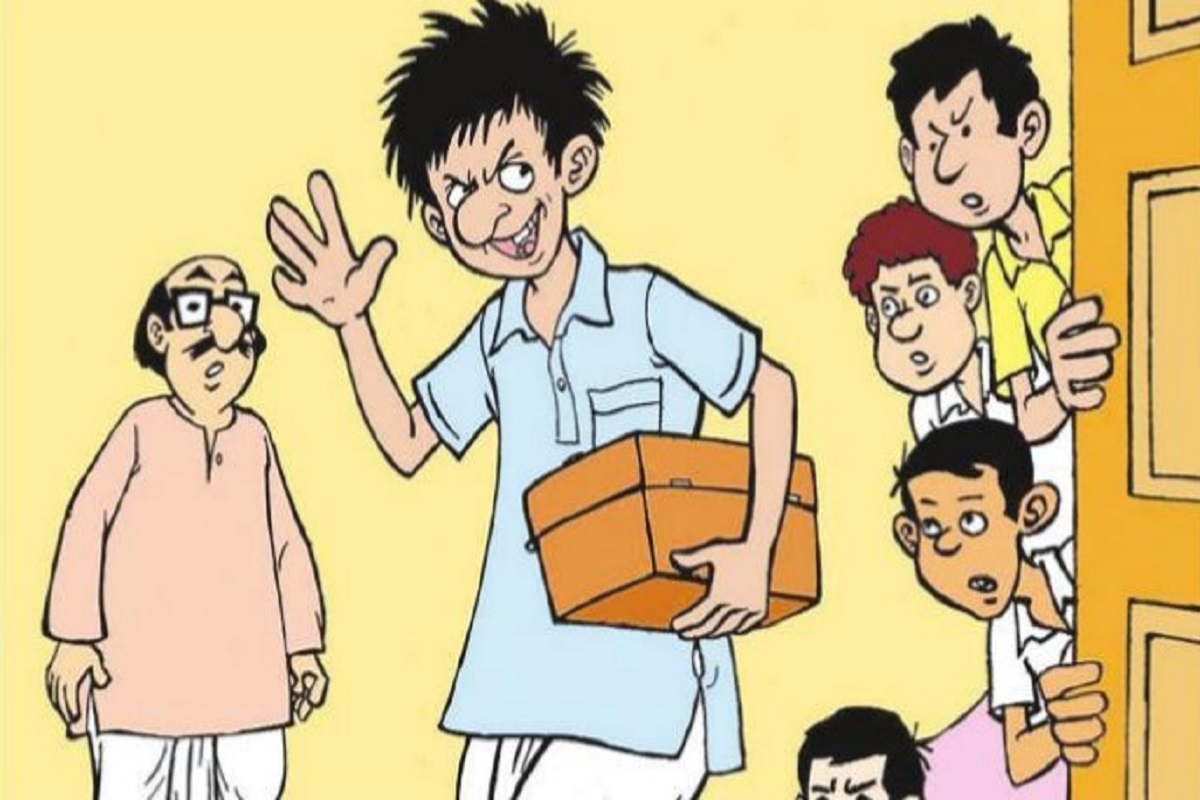

In Sukumar Roy’s more-than-a-century-old stories on ‘Pagla Dashu’, Dashu was a crazy schoolboy who could spoil a drama at a school function or set off crackers in the classroom. His acquaintances were always afraid of any mischief from him.

File Photo

In Sukumar Roy’s more-than-a-century-old stories on ‘Pagla Dashu’, Dashu was a crazy schoolboy who could spoil a drama at a school function or set off crackers in the classroom. His acquaintances were always afraid of any mischief from him.

At the end of one of the stories, Roy himself raised the doubt – was Dashu truly crazy, or did he just play tricks? Looking a little crazy may help sometimes. Herman Kahn, a pre-eminent futurist, argued in his 1962 book that to “look a little crazy” might be an effective way to induce an adversary to stand down.

Advertisement

Well, does playing crazy really pay dividends? The concept of the ‘madman theory’, however, is more than five centuries old, and its origin can be traced back to at least 1517 when Niccolò Machiavelli wrote in ‘The Prince’ that “at times it is a very wise thing to simulate madness.”

Advertisement

In the modern world, from the perspective of international relationships, of course, the madman theory got reinvented amid the changing geopolitics ever since the atomic age flashed into being in the Jornada del Muerto desert in 1945. Richard Nixon tried to apply it diligently.

Nixon-aide Robert Haldeman quoted a conversation during the 1968 presidential campaign, where Nixon confided to Halderman: “I call it the Madman Theory, Bob. I want the North Vietnamese to believe I’ve reached the point where I might do anything to stop the war.”

Then, in 1971, facing an impasse in negotiations to end the Vietnam War, Nixon’s national security adviser Henry Kissinger would portray the perceived madness of Nixon – and antinuclear spectre would effectively be unleashed – to both Hanoi and Moscow. Nixon as a madman is so prominent that, in his 2012 book ‘The Madman Theory’, Harvey Simon even tried to imagine what would have happened if Nixon had won the 1960 US presidential election and how Nixon, rather than Kennedy, would have handled the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis when the world stood on the brink of nuclear Armageddon.

The basic concept of the madman theory, however, had been brought into the power corridors of Washington even earlier. Kissinger wrote about the “strategy of ambiguity” in his 1957 book ‘Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy’, and Daniel Ellsberg’s famous 1959 lecture titled ‘ThePolitical Uses of Madness’ at the Lowell Institute of the Boston Public Library possibly ushered in a renewed era of ‘simulating’ madness among world leaders. And Dwight Eisenhower’s secretary of state John Foster Dulles was credited by many in Washington with having ended the Korean War by hinting to China that nuclear weapons could be used in Korea. It is well-known that both Nixon and Kissinger had respect for the ‘Dulles ploy’. It’s not very clear though how well this technique worked for Nixon.

Starting from Eisenhower’s handling of the Korean War, the madman theory was deeply rooted in the Korean peninsula. On the campaign trail in April 2016, Donald Trump criticized American foreign policy: “We are totally predictable. We tell everything. …We have to be unpredictable, and we have to be unpredictable starting now.” Trump later adopted the Nixonian style when his trade representative told South Korea: “This guy’s so crazy he could pull out any minute.” But did Trump succeed grossly with his projected madness? Penn State professor Roseanne W. McManus, however, perceived that Trump’s approach was counterproductive, as he was undermining the belief that his ‘madness’ was genuine. In any case, there’s a limit to how much presidential irrationality the American people could stomach.

Trump, however, claimed credit for using a ‘crazy’ approach to bring North Korea to the bargaining table, that no one else could have done. But his success story apparently ends inconclusively at the bargaining tables of Singapore and Hanoi. He possibly forgot that North Vietnam didn’t have nuclear weapons, but North Korea does. Then, what about the North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un? Hollywood movies such as ‘Team America: World Police’ (2004) and ‘The Interview’ (2014) promoted the idea that the North Korean leader and his senior advisers are mad.

Even Trump repeatedly called Kim Jong-un a ‘madman’, ‘crazy’, and ‘little rocket man’. But is Kim also playing a madman when he is repeatedly testing missiles to destabilize Japan and South Korea, and the United States as well when he tests intercontinental ballistic missiles? Then, in the backdrop of Russia’s Ukraine invasion, a new madman emerged in the geopolitical arena in the form of Vladimir Putin.

According to Martin Hellman, an emeritus professor at Stanford who specializes in nuclear risk, the West hasn’t properly caught on to Putin’s Armageddon game which, basically, is powered by the application of the madman theory. Back in 2015, Hellman stated that “nuclear weapons are the card that Putin has up his sleeve, and he’s using it to get the world to realize that Russia is a superpower, not just a regional power.”

From the perspective of the ongoing Ukraine invasion, when Putin ordered to place Russian nuclear forces on a ‘high combat’ alert, it certainly reminded us of the ‘madman’ theory of nuclear deterrence. Is Putin playing madman with his nuclear threat to Ukraine? Is he the newest one amid too many madmen in recent history? It is clear that the Pentagon is quite concerned about Russian falsehoods – that Ukrainian forces planned to use a nuclear ‘dirty bomb’ – paving the way for potential nuclear use by Russia.

Thus, if Putin is playing a madman, that is apparently working. With so many madmen these days, what about a theoretical framework of ‘Madman’ in international relations? Well, in her 2019 paper in the journal ‘Security Studies’, McManus identified four types of perceived madness, broken down along two dimensions.

“The first dimension is whether a leader is perceived to (a) make rational calculations, but based on extreme preferences, or (b) actually deviate from rational consequence-based decision making. The second dimension is whether a leader’s madness is perceived to be (a) situational or (b) dispositional,” argued McManus, using case studies of Adolf Hitler, Nikita Khrushchev, Saddam Hussein, and Muammar Gaddafi. She also argued that situational extreme preferences constitute the type of perceived madness that is most helpful in coercive bargaining.

As experts fear, the line between acting like a madman and being a madman is disconcertingly thin. Machiavelli, certainly, asked to be ‘wise’ while ‘simulating’ ‘madness’. What if too many people try to simulate craziness? And what happens when Trump and Kim, for example, play three-dimensional chess against each other? The standard madman theory simply becomes ineffective and dangerous. A new Machiavelli may be needed to reframe the complicated multi-dimensional modern madman theory

Advertisement