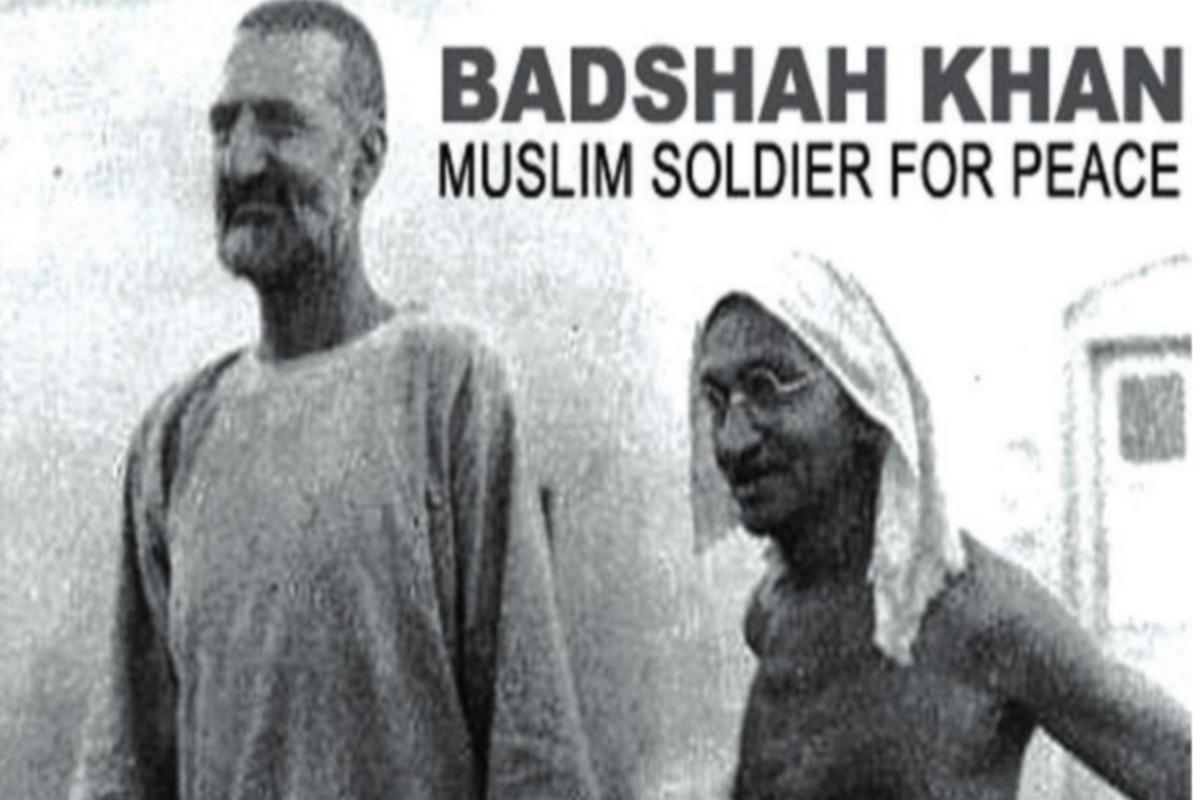

Badshah Khan furthered his nationalistic agenda by forming a group of young people who also tried to advance the cause of social progress and justice. All these were aimed at teaching the Pakhtoon people principles of industry, economy and self-reliance. Khan met Gandhiji and Nehru at this time and this friendship was to last for their lifetime. The formation of the “Red Shirts” or “Khudai Khidmatgar” (Servants of God) played an unforgettable role in India’s free- dom struggle and promoted Khan’s ideas of social reform, unity, independence and non- violence. A Khudai Khidmatgar, Khan felt, had first to be a man of God or a servant of humanity which would demand of him purity in thought and action accompa- nied by non-stop honest and selfless work. The volunteers, therefore, had to learn some skills to be offered to millions of people. Khan told his followers: “A per- son who renounces the sword dare not remain idle for a single minute. Idleness corrodes the soul and the intellect. A person who has renounced violence will take the name of God with every breath and do his work all the twenty-four hours.” Besides believing that lear- ning skills like spinning and weaving could promote the cau- se of peace, Frontier Gandhi also pushed for the ideal of self-suffi- ciency: “We will wear only the clothes that we ourselves pro- duce, eat only such fruits and vegetables as we raise there and set up a small dairy to provide us with milk. We will deny our- selves what we cannot ourselves produce.” Khudai Khidmatgars were highly disciplined and had their own flags, initially red and later tricolour, and bands of bagpipes and drums. They seemed like an unarmed army of peace and the emphasis of their training was on forbearance and tolerance. Each member took an oath: “We are the army of God, / By death or wealth unmoved, / We march, our leader and we, / Ready to die.” Khan, a devout Muslim, taught his people that being a Muslim meant complete sub- mission to God’s will. He would say: “I give you the ‘weapon of the Prophet, patience and right- eousness. No power on earth can stand against it.” Not only Islam, Ghaffar Khan believed that all religions are benevolent: “Every religion that has come into the world has brought the mes- sage of love and brotherhood. Tho- se who are indif- ferent to the wel- fare of their fellow- men and whose hearts are empty of love do not know the meaning of religion.” The conviction in non- violence on the part of Khan was an unusual one as the society he be- longed to was not much accustomed to it. But, for Khan, non-violence was not merely a belief; it was a way of life. He was ready to cou- nter any charge against it: “Some remarked that the Pakh- toons are a brave and powerful people, but Ghaffar Khan wants to turn them cowards… The fact of the matter is non-violence is a great force in itself, just as vio- lence is a force. The difference is that the weapon of non-violence is preaching or ‘tabligh’, while the weapon of violence is the gun.” Not only men, a large number of women too joined Khan’s movement as it promoted equ- ality for women and female edu- cation. Pathan women partici- pating in non-violent campai- gns would frequently take their stand facing the police or lie down in orderly lines holding copies of the Quran. The British, however, thou- ght of Ghaffar Khan’s movement as a ruse. To them, a non-violent Pathan was unthinkable, a fraud that masked something cunning and darkly treacherous. In the most horrifying case, the British killed about 400 Khi- dmatgar members in Peshawar on 23 April 1930. The massacre at the Qissa Khawani Bazaar became a defining moment in the non-violent struggle to drive the British out of India. In the face of raining bullets of the British rulers the Khidmatgars showed utmost patience and commitment to the ideal of non-violence, chanting God’s name as they went to their death. The mas- sacre reminded everyone of the show of British brutality at Jallian- wala Bagh. When the co- ercive tactics of the British failed, they played the communal game for breaking the movement. But Khan, though a devout Muslim, had a universalis- tic approach. He said that “all revealed reli- gions have come to us from God. They have come in order to bring unity, love and amity in this world…It is incumbent upon the followers of all religions to rid the world of hate and intol- erance.” He continued to work for religious harmony even when he was in jail. He requested the jail authorities to arrange the teach- ing of Quran for the Hindus and Bhagavad Gita for the Muslims. Khan himself would often read the Gita and joined Gandhi in daily prayers and also in the readings of Tulsi Ramayana. Comfortable with Hindu friends, comrades and collea- gues, Badshah Khan also had many Christians and westerners among his friends and he tried earnestly to dispel misunder- standings about the Pathans among people of other faiths and societies. Like Gandhi, whose non- violence was based on the Jain concept of Ahimsa, Khan’s too was spiritual and it was based on Islam’s ‘Sabr’ which implies holding on to a righteous cause without retaliation. Like Gandhi, Khan too lived like an ascetic and his personal belongings were nothing more than a small bundle of spare clothes. While in prison, Gandhi and Khan shared their reading glasses. But what is more impor- tant is that they shared a vision of asceticism and self-purifica- tion. Gandhi said of him, “The more I see him the more I love him”, and Ghaffar Khan in his turn felt uncomfortable in being called Frontier Gandhi as he thought that the name of Gand- hi should be reserved for one and only Mahatma. Partition pained Badshah Khan as much as it did Gandhiji. He too felt betrayed by the Con- gress, and told Gandhi and the Working Committee that they were “throwing us [Pathans and Khudai Khidmatgars] to the wolves.” The ideological differences with the Muslim League made Khidmatgars truly hapless in their own land under Pakistani domination. True to Khan’s fears, the Khidmatgars were treated sav- agely after the Partition and they were dubbed “friends of India and the Congress and traitors to Pakistan.” The Khudai Khidmatgar was banned as a political party and most of the Khidmatgars were thrust into prison includ- ing Khan. Though released from prison due to his deteriorating health condition, he was never happy with any regime in Pak- istan. He was awarded the Bharat Ratna in 1987, but in the follow- ing year, he breathed his last. On his demise, the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan was opened to allow tens of thou- sands of his followers from Pak- istan to travel to Afghanistan to attend his funeral. It is indeed a tribute to the life and activities of Frontier Khan that even the warring Mujahedeen and Soviet-backed Afghan government agreed to a ceasefire for three days. His dream of seeing India getting freedom in the undivid- ed state was ruthlessly shat- tered, yet his death saw people of the divided nations united in their grief and homage to the great soul. (Concluded)

The writer, a PhD from Calcutta University, teaches English at the Government- sponsored Sailendra Sircar Vidyalaya, Shyambazar, Kolkata

Advertisement