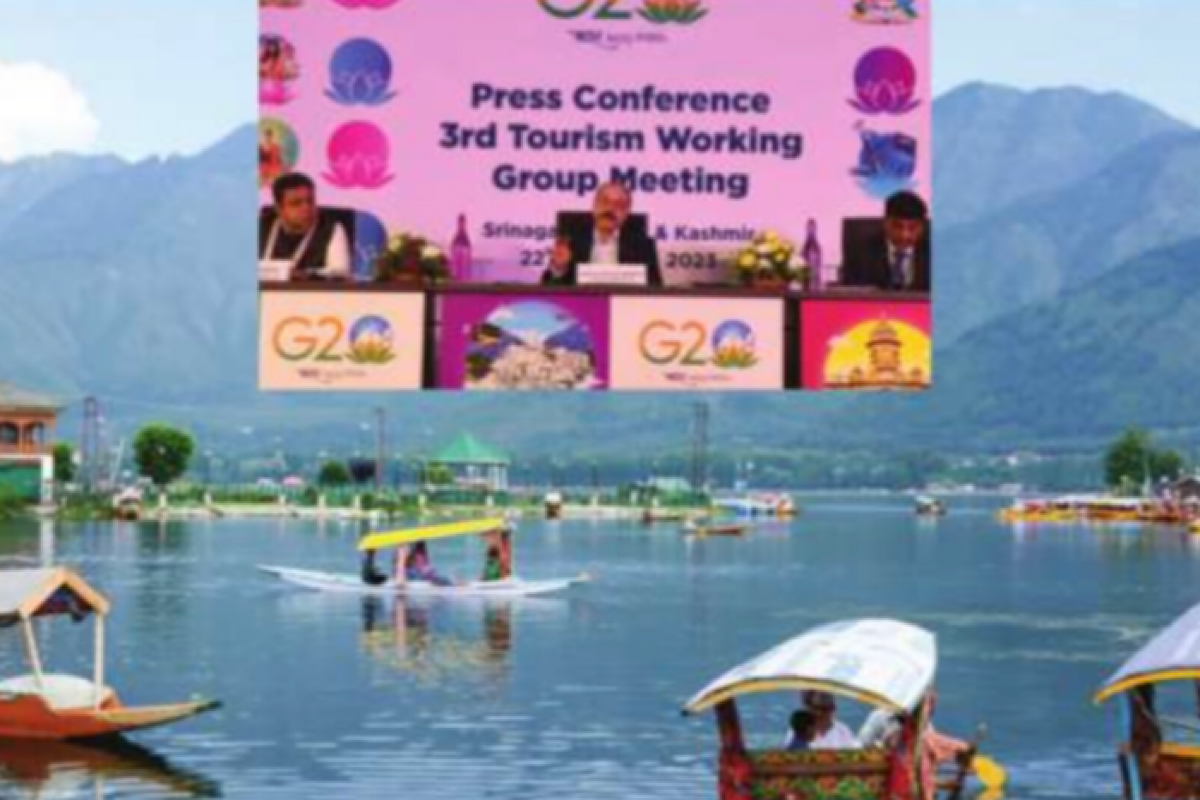

Four years after the abrogation of Article 370, are winds of change blowing through the Valley, auguring a new era of peace? Recent developments, particularly since the holding of the G-20 Tourism Ministers’ meeting in Srinagar in May 2023, seem to indicate the beginning of a new era of peace. One of the aims of the Government of India in holding the meeting in Kashmir was certainly to highlight that normalcy was returning to the Valley.

There has been a remarkable revival of the tourism industry in Kashmir with more than 18 million tourists visiting Jammu and Kashmir in 2022, compared to almost 13 million (including the tourists visiting Ladakh) in 2012. Spurt in tourism has brought in its wake rejuvenation of Jammu and Kashmir’s economy, as income from tourism constituted nearly 15 per cent of the State’s GDP (SGDP) before it was split into two Union Territories (UTs) Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh. Nearly 50 per cent of J&K’s population is directly or indirectly involved in tourism-related activities.

Advertisement

In addition to agriculture, tourism is the most important sector for income generation and job creation. According to reports by recent visitors to Kashmir signs of economic recov- ery are visible, not only in Srinagar but also in other parts of the Valley, with the opening of malls in different cities, shops remaining open even after the sun sets, restaurants and hotels doing brisk business, and tourists thronging the Dal Lake area for shikara rides, and visiting picturesque spots away from Srinagar, Sonmarg and Gulmarg. According to the National Sample Survey Report, the unemployment rate dipped to 6.8 per cent in January-March 2023, compared to 8.2 per cent a year ago, while the overall economy, which is heavily agrarian, grew by 8 per cent during 2023.

These indicators seem to suggest that normalcy is returning to Kashmir as people, tired of years of militancy and its adverse effect on their lives, are now turning to bread and butter issues. To give a further boost to this image of normalcy returning to Kashmir, the first All India Women Cricket Championship was organised in the militancy-hit Doda district in May 2023, in which teams from UP and Hyderabad also participated. These indeed are hopeful signs; but there is no room for hubris. Peace in Srinagar and in other places in the Valley is maintained by the overwhelming presence of security forces.

It may not be out of place to mention here my own experience when I visited Manipur in October, 2017. Everybody warned me against the proposed trip, as Manipur was still under the AFSPA, indicating that matters were far from normal.

But when I landed in Imphal on a sunny day, I was pleasantly surprised to find that the city was bristling with activities. We visited a number of places within the city, and also places far away from the city, including the INA Museum and the Lok Tak Lake, and everywhere people were extremely courteous and cooperative.

Manipuri women claimed that they did not like the idea of being dependent on their men folk, and that they were competent enough to take decisions on their own, even in economic and business matters, which was amply demonstrated by the functioning of the

all-women market in Imphal. What other proof was needed to show that Manipur was

in peace? But the overwhelming presence of security personnel ~ the Army, the Assam

Rifles, the CRPF, and the local police forces ~ in the city and other places made me realise that things were far from normal.

The hotel where we stayed was right in the middle of the city; nevertheless we were advised not to go out in the evening, as Imphal was not safe for visitors (and even for locals) in the evening, because ‘rebels’ often kidnapped people for huge ransoms. Who were these ‘rebels’? After some cajoling came the reply: the tribals living in the hilly areas, appar- ently referring to the Kukis and the Nagas. Any perceptive observer visiting Manipur could discern that there were latent con- flicts in Manipur between the Kukis and the Nagas, between the Kukis and the Meiteis, the dominant ethnic group who live in the Valley, and between the Nagas and the Meiteis, and occasionally these latent conflicts erupted into violence.

These conflicts were being ‘managed’ by maintaining a delicate balance between and am- ong the different stake-holders to sustain peace in the State. But this was a fragile peace as has been proved by the sudden out-break of violence in May 2023, which is still continuing.

Violence was triggered by an order issued by a Bench of the Manipur High Court, headed by the Acting Chief Justice, in April,2023, in response to a peti- tion submitted by some members of the Meitei Tribe Union (MTU). The High Court directed the Manipur government to consider the case of the petitioners for inclusion of the Meitei community in the ST list under Article 342 of the Indian.

Constitution favourably, and write to the Union Ministry of Tribal Affairs, within a month to recommend such inclusion. The Kukis responded to this order violently which was matched by an equally violent response from the Meiteis. If one goes by the example of Manipur, one may argue that the current peace in the Kashmir Valley may also turn out to be a fragile one and a single misstep by the government at the Centre as J&K is being directly ruled by New Delhi since the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019 for gaining political dividend, may change the scenario. Take, for example, the three Bills introduced in the Lok Sabha 26 July 2023 relating to Jammu and Kashmir.

The first of these ~ the Constitution ( Jammu and Kashmir) Scheduled Tribes Order (Amendment) Bill 2023 introduced by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs ~ seeks to ensure reservation for Paharis in government jobs and has triggered protests by the Gujjar community. When the Union government had started the process of adding the ‘Pahari Ethnic Group’ to J&K’s ST list, existing STs, particularly members of the Gujjar and the Bakarwal communities, opposed it on the ground that it would allow economically advanced groups to take advantage of reservations, and that opposition has not ceased. The Gujjars have now come out on the streets protesting against the move and plan to intensify their strug- gle, unless the Centre relents. They call it a move by the BJP as a part of its electoral politics, to win support of the Pahari community, while the latter has welcomed the move.

It is important to note that Rajouri and Baramulla, along the LoC, are dominated by the Gujjars and Pahari speaking people, who play a significant role in the Assembly and Parliamentary elections in J&K. In the past, both these communities supported the National Conference (NC) and the PDP; the BJP’S move to court the favour of these communities was certainly influenced by considerations of electoral gains.

The Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) chief and the former Chief Minister of Punjab, S S Badal, has now come out with the demand that two assembly seats be reserved for Sikhs in Jammu and Kashmir. Another Bill has also been introduced in the Lok Sabha the J&K Reorganisation Amendment (2023) Bill ~ that seeks to provide reservation of seats for Kashmiri Pandits and

migrants from Pakistan-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (POJK). It has been opposed by the non- BJP political parties. Home Minister Amit Shah while touring crisis-hit Manipur toward the end of May, had said that the Manipur High Court’s order on ST status for the Meiteis was ‘given in a hurry’. Has the Centre also not acted in a hurry while introducing the J&K Reorganisation Amendment (2023) Bill in Parliament at a time when the Apex Court is considering a bun- ch of petitions filed by the CPI (M) and several others challenging the validity of the J&K Reorganisation Act of 2019?

Within a few months of winning the parliamentary elections in May 2019, the BJP-led central government abrogated Article 370 of the Constitution that gave a semi-autonomous status to the State of J&K, along with Article 35A that gave the State Constituent Assembly the power to decide who would be considered the ‘permanent residents’ of J&K, as they would enjoy cer- tain rights in the matter of owning land, getting government jobs, gaining admission to gov- ernment educational institutions and educational scholarships etc., denied to those from other states of India who might be residing in J&K. Article 35A was included in the Constitution to enable the ‘permanent residents’ of J&K to maintain their separate identity ~ while being a part of the Indian state. (Incidentally, similar provisions have also been included for the States in India’s north-east under Article 371.)

Article 370 was abrogated by using a questionable legal process; since the State Assemb- ly was dissolved earlier, there was no mechanism available for ascertaining the will of the people. To suppress opposition, thousands of arrests were made, including arrests of political leaders, most of whom were released by 2021-22; internet services were banned and J&K became virtually a ‘police state’.

The government worked overtime to prove that peace had been restored in Kashmir; but the reality was different as nearly 78,000 paramilitary forces were deployed in J&K, in addition to the local police. Contrary to the government’s claim that there had been no incidence of violence in Kashmir after the abrogation of Article 370 on 5 August 2019, India Today TV reported on 10 October that in encounters with militants after 5 August, at least 10 militants had been killed, and in stone-pelting incidents some 100 para- military jawans had been injured. This information was sourced from a document that was prepared for internal use by the paramilitary forces.

(The writer is Professor (Retd.) of International Relations, and a former Dean, Faculty of Arts, Jadavpur University)