The increase in the number of senior citizens in India has been rapid ~ 24.7 million in 1961; 104 million in 2011; 138 million (preliminary estimate) in 2021 and a projected 194 million in 2031, with the percentage share in total population in these years being 5.6, 8.6, 10.1 and 13.1 respectively ~ whereas the government’s support for the old age social security has not been moving in tandem; rather, it is tangibly on the wane.

The new pension scheme for its employees, inferior to the existing one, is a case in point. More disturbing is the denial, due to some flimsy objections, of the higher pension right to a large number of employees already covered under the Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) scheme, not to speak of the total exclusion of a category of employees recruited after 1 September 2014.

Advertisement

The grounds, as we will see later in this article, though technically accurate and perfectly legal are nothing but the devices to deny the higher pension, an afterthought of the government to withdraw what was introduced with so much enthusiasm in 1996.

A quick review of the scheme first. The EPF, the Old Age Social Security Scheme for providing provident fund to workers in factories and other establishments, was introduced in 1951 through a presidential ordinance, which itself speaks of the urgency the government of the day felt for workers’ welfare; the ordinance was converted later into a central enactment in 1952.

The employees’ pension scheme was added in 1995 with a modest pension benefit engineered through a ceiling on pensionable salary. It was Rs. 5,000 when the pension scheme came into force and remained so till 2001 when it was hiked to Rs. 6,500 and to Rs 15,000 from September 2014. These were the sums on which both the PF contributions were made and the pension calculated.

For instance, a person who has completed the full pensionable service, say, 35 years, and had paid during the service time the requisite contribution together with her or his employer on the statutory wages of Rs. 5,000 would get the monthly pension of Rs 2,500 as per the pension formula: Pension = Pensionable Service X Pensionable Salary/70.

The pensionable salary means the salary on which the contribution is paid which is the statutory ceiling of Rs. 5,000 or less if the actual salary is lower than the ceiling. The subsequent increased ceilings of Rs. 6,500 and Rs 15,000 entail a maximum pension of half these sums.

This, the ceiling, is exactly the reason why those with high salaries, maybe more than a lakh rupees get paltry pension sums like Rs 1,500 a month. Since the pension sum was too insignificant, disproportionately lower than the last drawn salary, the government brought a change effective 16 March 1996 allowing the EPF contribution on the actual salary above the ceiling like Rs.5,000, etc. which facilitated the higher pension proportionate to actual salary instead of ceiling amounts.

In response, a large number of employees and employers made higher contributions to receive higher pension. But that was denied when it became due on the ground that they did not file their options for a higher pension although they had paid extra money.

This led to the employees waging a long legal battle in different high courts, Delhi, Rajasthan Kerala, etc. and finally in the Supreme Court. The threejudge bench of the Supreme Court gave its judgment on 4 November 2022. Unfortunately, the ordeal of the senior citizens continues with the impractical eligibility conditions of the government.

Paying the higher contributions alone is not sufficient for the EPF Organization but it should be backed by the exercise of the option for higher pension within the timeframe and style it wanted; the very payment of higher sums itself is not accepted as proof enough for the employee’s intent for higher benefits including pension accruing out of it.

Not only that, there are several other peculiar norms. Just one example in a particular situation on options: the direction implies like the authorities saying “if you did not exercise the option, you are not eligible. If you have exercised it and I rejected it then you are eligible, but, it is your responsibility to show the proof of your application and my rejection; the wrongful rejection and the wrong interpretation is my exclusive right, not yours”.

While the Supreme Court gave its verdict on 4 November 2022 the process is continuing and the EPFO has recently extended time till the year-end for employers to submit their part of the information on the higher pension applications; some 17.5 lac persons applied.

All this suggests that the government has found the higher pension scheme not feasible and wants to minimize the burden to the extent possible. In fact, the higher pension scheme has been totally withdrawn for post-September 2014 recruits. The non-feasibility argument of the government is based on its actuarial evaluations.

But the available data and the need for old-age security and common sense suggest that it is not at all difficult to implement since the pension is contribution-based and higher pension is higher contributionbased.

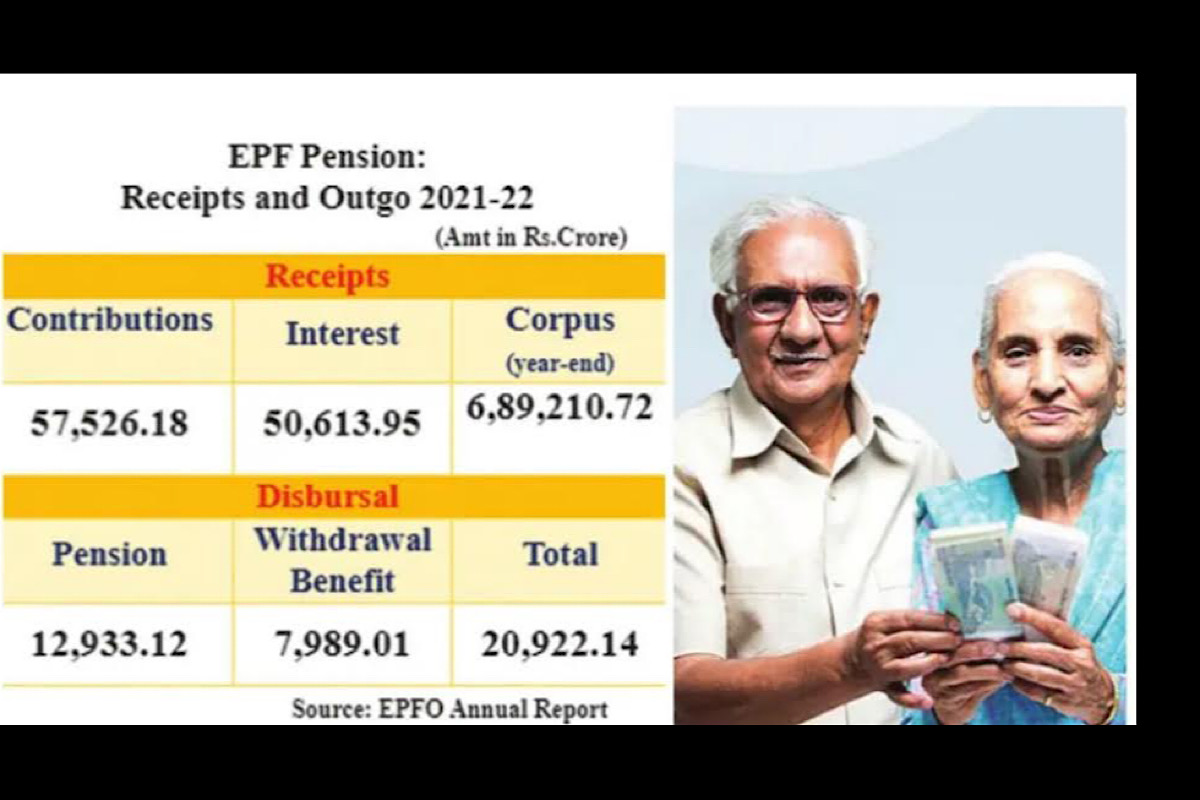

The latest available EPFO data shows that the accumulation in one year of 2021-22 pension corpus is Rs. 57,526.18 crore and interest in one year on the accumulated corpus is Rs. 50,613.95 crore. Add to this, the unclaimed funds, which it calls the deposits in inoperative accounts, is more than Rs.30,000 crore.

The accumulated corpus is Rs.689,210.72 core. Against this heavy amount, pension payment in one year to 72.74 lac pensioners is just Rs.12,933.12 crore. Together with withdrawal benefit of another Rs. 7,989.01 crore the total payout in a year is Rs. 20,922.14 crore, that is, 19.34 per cent of the annual receipts into the pension fund.

So, there will never be a cash problem for allowing higher pension because more funds will be accruing year after year, much more than the need; the EPFO already has a member base of 7.74 crore and the number will keep increasing in the expanding economy.

Even assuming, though most unlikely, that some shortfall ever occurs, it will be the duty of the government to come to the aid of the EPFO to meet its social obligation. So, the dearth is not of money but of the will; a decent EPF Pension equal to half the last drawn salary can be given to all the members, to ensure their dignified life after retirement.

(The writer is a development economist and commentator on economic and social affairs)