The most difficult component of the superconducting cyclotron was called cryostat. It is a large vessel full of liquid helium into which the coils of the superconducting wire are immersed. These coils, once energised, produce the necessary magnetic field. We went around the length and the breadth of India from Hardwar to Trichinapalli from Bombay to Delhi ~ a tour that yielded no result whatsoever.

We negotiated with the most important companies; not one could furnish a viable proposal. So one was forced to abandon the “Make in India” philosophy, not liked by many but we had no option. I approached the famous Ansaldo Company of France and after tedious negotiations, the contract was eventually signed. So, at last, the foundation was laid by Chief Minister Jyoti Basu on 18 June 1997. Henry Blossar was right.

Advertisement

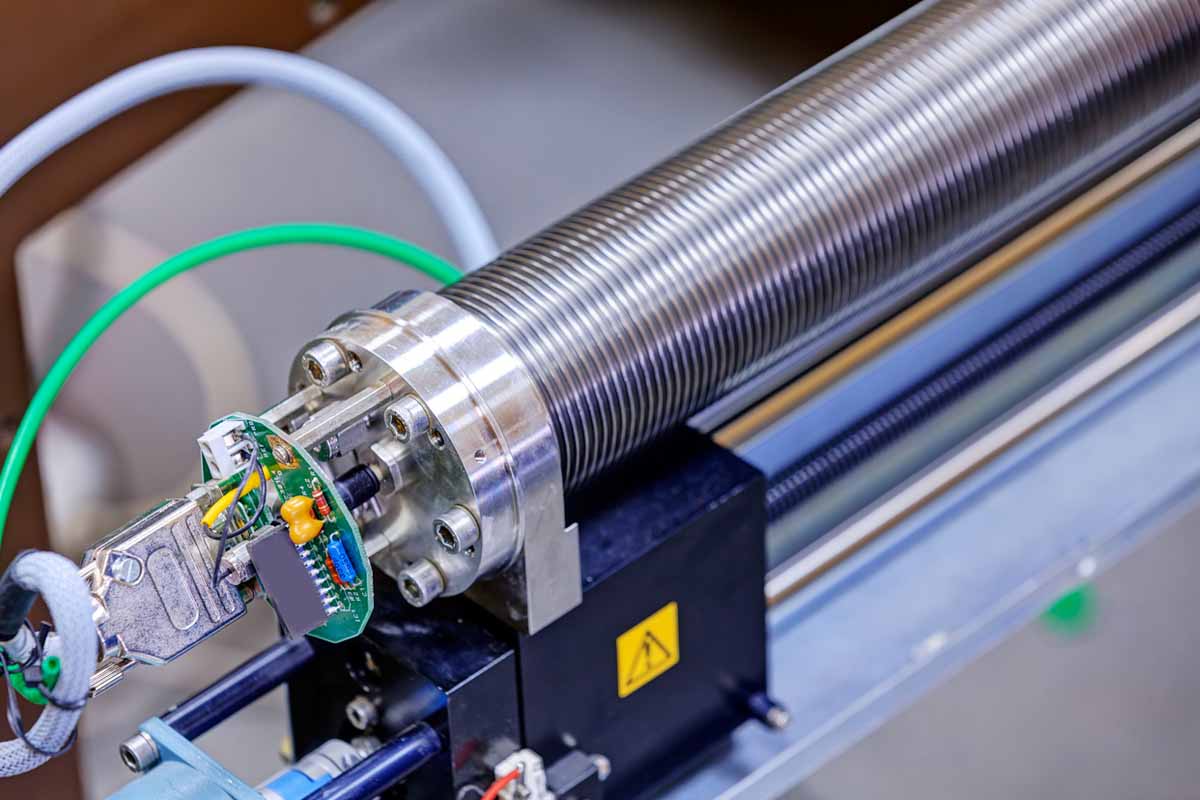

None of us had any experience on cryogenic (liquid helium related) technology. We had to learn everything from scratch and struggle to go ahead. It was a slow and demanding process. Winding of 42 km of superconducting wire on the coil was yet another challenge. Interestingly enough, a small firm in Pune, which followed the R&D philosophy. A PhD from MIT, the chief didn’t opt for a steady job with a huge pay packet, but thrived on the difficult R&D project with a group of motivated innovators, as partners.

The coil winding machine was in place within a short time. The building was designed and eventually it was built; as usual; it took much longer than the stipulated time, keeping in mind the radiation protection. The magnet was manufactured by the Heavy Engineering Corporation, a splendid job once again. Eventually after 12 years of arduous work, the internal beam of the superconducting cyclotron was sighted on 25 August 2009 at 4 in the morning.

I conveyed the news of this great achievement to several countries. The Minister of State for Atomic Energy, Mr. Chavan sent a very nicely worded massage. But some people still remained unhappy. They asked: How can you say the cyclotron in commissioned when the external beam has not been obtained.” I was furious; I have been associated with the cyclotron since my days as a research fellow in King’s College, London.

The Michigan superconducting cyclotron was declared “commissioned” once the internal beam was sighned; there was an international conference at Michigan which I attended to celebrate that event. But these unhappy people remained unhappy. With the benefit of hindsight these people are accustomed to failures or no success. Hence they are averse to success. To get the external beam, the beam from the cyclotron has to be guided through a complicated and compact magnetic and electric configurations with very little manoeuvring scope.

It is not a very easy task to extract the beam. In fact, I know Michigan faltered; even with Michigan’s experience, Texas also faltered. But, so what? Keep at it with mapping the details of the configurations in detail and we shall get there, I advised. After a painful and tedious process, just when the deep frustration was about to blur our effort, on 26 November 2019, the external beam was sighted. I never felt more elated Dr. Sumit Som the present Director and his team had done an incredible job.

In India, failure in general is more a part of our lives than success. Lack of everything in right proportion is the reason. We are born pessimists. But on 26 November, 2019, not only was I vindicated but felt that the youth of today’s India are for more optimistic. They have neither seen nor experienced the poverty of yester years. I firmly believe that it is the honest industry of the youth that will push India forward.

Forget politics! In between, room temperature cyclotron and the superconducting cyclotron, some of us started thinking that after “all the years of experience, we must give something back really relevant and essential to our society, for the benefit of our people”. It occurred to me that a medical cyclotron of extreme reliability, should be brought in for producing very special (SPECT) isotopes for detection of cancer tumours.

I had learned from my oncologist friends that Palladium isotopes, is a sure cure for prostate cancer if detected within reasonable time. This isotope is bought from abroad at an almost prohibitive cost. Cardiologists told me that Thallium, essential for prognosis of the function of the heart, is also hugely expensive. So, after going from pillar to post (The Statesman ~ 30 November 2018) we got the financial approval from the Government of India to buy the 30 MeV cyclotron from a Belgian company, IBA.

Once again the building took a great deal of time to come up. But now the five acres of land given free by the then Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee looks like a “garden of cyclotron” near the Neotia housing complex. The machine in big crates were lying in an airconditioned environment for quite some time, waiting for the building to be ready. I had my worries; for such a long transit the machine might go rusty But all the worries were over on 18 September 2018 when the machine sprang to life and started working instantly almost like a magic touch.

Now, in Kolkata, three cyclotrons are working without any glitch. Long years ago, at the height of the Bengal Renaissance, science, including its application, along with literature dominated and guided the spirit of Bengal. Not a single area of our cultural canvas was left out in that campaign. Now, science in Bengal has gone behind the purdah. Nobody outside the world of science knows what is happening in the realms of science and literature. Scientists are content, publishing papers, and literature and theatre have become parochial, provincial and claustrophobic.

We are happy with Bengali culture and don’t really care about world culture at all. Consumerism and morcha politics have taken deep roots in our society. Where is Acharya Prafulla Chandra Roy and his Bengal Chemicals, where is a Bose, where is a Saha or Mahalanobis, pioneers in their fields? Where is Rabindranath Tagore, or at least a figment of his extraordinary genius. As a Bengali, I feel extremely distressed.

Yes, we have a lot of talented students. But the best go abroad and make a name for themselves. There is no passion, no commitment for putting Bengal at the centrestage. We are happy with our own lot and we don’t look forward. The three cyclotrons are a marvellous example of the hard work by our scientists and engineers Kolkata is now a city with cyclotrons in the frontier.

(Concluded)

(The writer is INSA Senior Scientist and former Homi Bhabha Professor, DAE, former Director, Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics and Variable Energy Cyclotron Centre)