The Supreme Court’s five judges are to hear and take a view as to whether talaq pronounced three times in one sitting and its coming into effect immediately is valid or not.

The main proponent in favour of its validity are followers of the Hanafi School of thought who form a substantive majority of the Muslim community in India and they, on their reading of the Holy Quran and interpretation given by Ulemas, are strongly of the firm opinion and belief that three talaqs given in one sitting comes into effect immediately, a consequence of which is that the relationship between two individuals comes into the category of a prohibited tie. At the same time, they agree that this procedure of pronouncing talaq is not the best way of pronouncing the end to a relationship. But because it makes the relationship prohibited, it is effective immediately.

Advertisement

It is a matter of faith and belief based on divine law. For Muslims, the concept of marriage has come from the Holy Quran. The marriage between two individuals has a contractual basis with mandatory Mehr for the benefit of woman. The religion commands that there should be no dowry, no big ceremonies, a wife and a husband are not rivals but companions and their responsibilities. The concept of a witness, while performing nikah, is to ensure that the matrimonial relationship becomes public. At the same time, a husband and wife have been subjected to certain conditions for termination of matrimonial relationship. This is a package in its entirety. If the marriage comes into existence as per one school of thought, one party should not take the stand that he or she will be not be bound by it for the termination. There is no problem with followers of all schools if at the time of marriage, the parties put their conditions and prefer not to be governed by the Hanafi school.

It has been rarely pointed out in this discussion that in the year 1937, The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act came into effect which recognized that dissolution of Muslim marriage shall be as per Muslim Personal Law. As reflected in the preamble of the Act, it came into force at a time when Muslim woman refused to be governed by the then customary laws describing them as simply disgraceful as they adversely affected their rights’. Thereafter, Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution of India, in Part III, protected the right to ‘practise and propagate religion including the right to manage religious institutions.

In 1979, the Supreme Court, in Krishna Singh V Mathura Ahir held that ‘the learned Judge failed to appreciate that Part III of the Constitution does not touch upon the personal laws of the parties. In applying the personal laws of the parties, he could not introduce his own concepts of modern times but should have enforced the law as derived from recognised and authoritative sources of Hindu law, i.e., Smritis and commentaries referred to, as interpreted in the judgments of various High Courts. In the years 1994 and 1997, the Supreme Court has rejected petitions seeking reform in Muslim Personal Law.

We have seen, despite Indian Evidence Act being in force coupled with the right to property guaranteed under Article 300A, to decide title disputes, an issue was framed in relation to faith of a community and a serious consideration has been given by the Allahabad High Court to faith and belief while deciding the title dispute relating to Babri Majid-Ramjanmabhoomi. On the basis of faith and through legislative reform, penal provisions have been created against killing of a particular animal. The courts have upheld the validity of such laws and punishment awarded in case of violation of that law. Nine Judges of the Supreme Court in 1994, in the S R Bommai case, held that ‘Secularism is one of the basic features of the Constitution. While freedom of religion is guaranteed to all persons in India, from the point of view of the State, the religion, faith or belief of a person is immaterial’. Two years later, three Judges of the Supreme Court held that the term ‘Hindutva’ is related more to the way of life of the people in the subcontinent. It is difficult to appreciate how in the face of these decisions the term ‘Hindutva’ or ‘Hinduism’ per se, in the abstract, can be assumed to mean and be equated with narrow fundamentalist Hindu religious bigotry’. In my view, in all these cases, the court has acknowledged faith in the larger sphere of public law.

Right now, the Supreme Court is seized of the matter because it wanted this issue to be examined while deciding the case of Prakash v Phoolwati wherein the issue related to the law of Hindu succession. A judicial order was passed relying upon an earlier Supreme Court judgment of 2003, John Vallamattom V/s Union of India, where it was held that ‘succession and the like matters of secular character cannot be within the guarantee enshrined under Articles 25 ans 26. There, the issue was restriction against a Christian while making a will for religious and charitable purposes. The Court held that the religious freedom of a Christian should be at par with the others and struck down the discriminatory provision against the Christian. The paragraph relied upon in the case of Prakash in reference order, according to me, was not called for and at the most that could be obiter. In the same judgment of 2003, the other judge has supplemented the reasoning by relying upon the guarantee under Article 25 and 26 of a Christian to make a will for religious purpose.

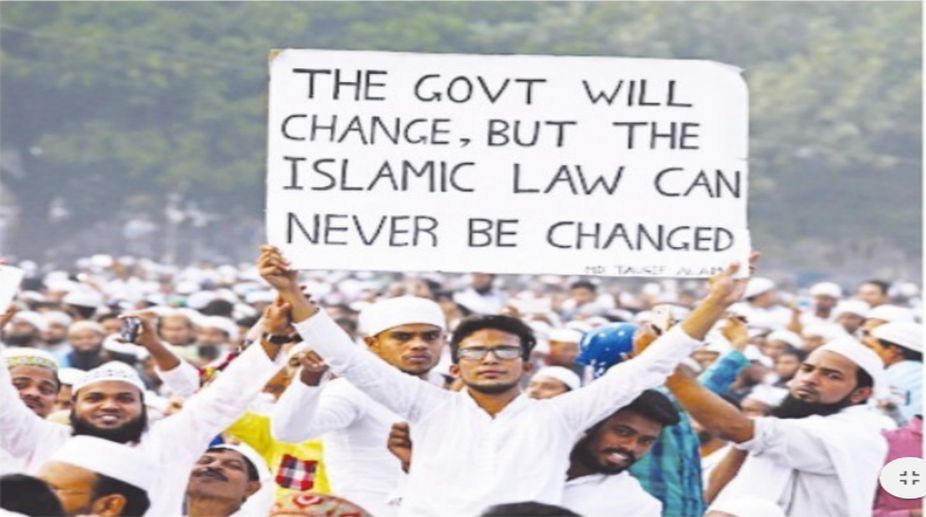

There is no doubt that every practice in the Muslim community is not right and there is need to improve many things. The question is who should correct them? Judicial pronouncements, legislative reforms or through the efforts of the community itself?

In my view, on issues of faith and belief, reform should not be through judicial pronouncement. We have seen the fate of the Jallikattu verdict. The principle of equality cannot be applied without considering the fact of cultural differences and religious followings which are core to that community and this makes them a group for their personal relations. The plain principle of equality cannot be applied across all women in the country. On this issue, the best would be to encourage the community to come up with reform. The community should also, without delay, make the effort to reach consensus on certain basic issues which they consider very important in the field of personal law.

The writer is Advocate on Record, Supreme Court of India.