When Shyam Benegal credited Satyajit Ray for revolutionizing Indian cinema

Shyam Benegal praised Satyajit Ray as the genius who redefined Indian cinema, leaving an unmatched legacy that transformed filmmaking.

Ray was fond of the great Hollywood masters, and never encouraged the arty-arty film-makers with no audience focus and scant responsibility to get the financiers money back. The director expresses himself with others money and for him to remain creative, has to understand his primary audience and devise means within available resources, to reach that audience.

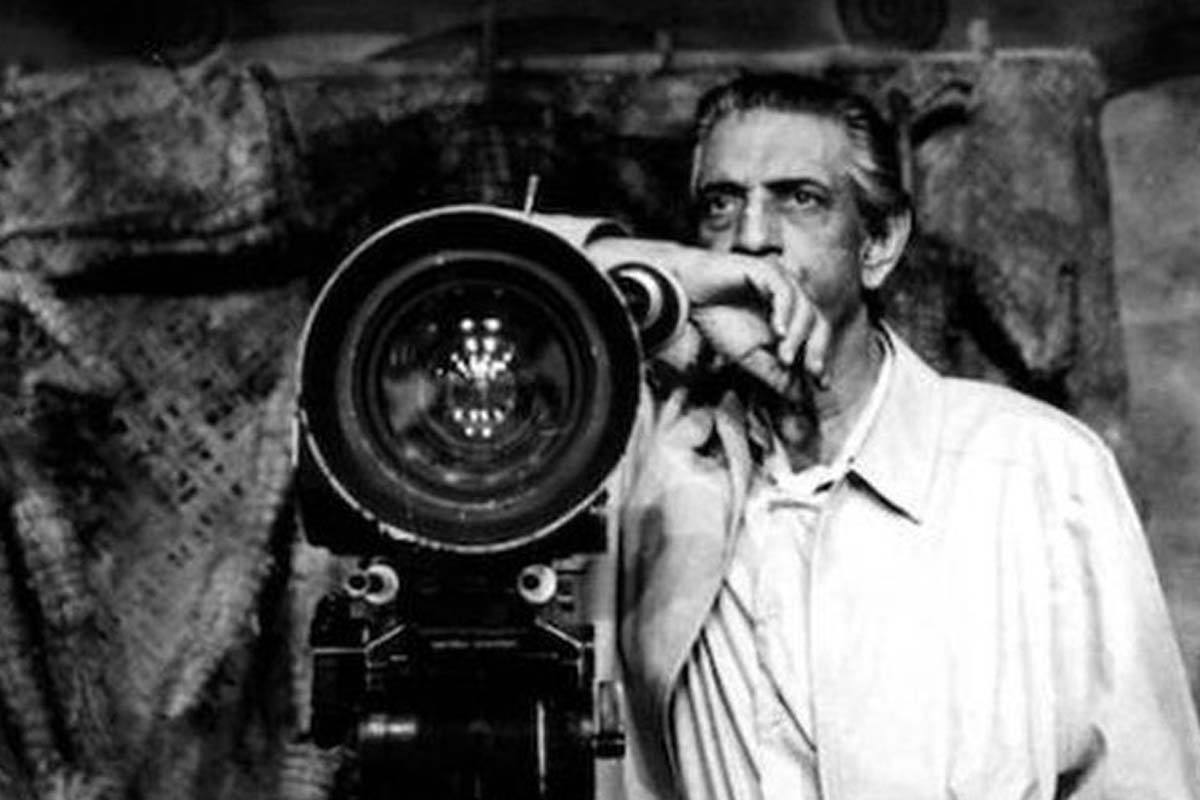

Satyajit Ray (Photo: Facebook)

Satyajit Ray is acclaimed universally for his majestic body of work. When Ritwik Ghatak hailed him as the harbinger of a new era and the only person in India who understood the medium of cinema, or when Herzog, the protagonist in Saul Bellow’s novel, identifies with the mother of Apu and Durga after the latter’s death in Pather Panchali, one understands the power of Ray’s cinema to touch hearts across cultures.

What characterises his unique and sustained contribution? Having prepared himself fully to make films, Ray strove to elevate Indian cinema to his own stature. Besides the illustrious family lineage, his early association with Santiniketan when Tagore was alive, his acute observation of world cinema, his grounding in music ~ Western and Indian, together with his passion for photography and sketching coalesced to give him the confidence to take risk and plunge into cinema.

Advertisement

His struggle during the years of making Pather Panchali is now part of filmlore. The film succeeded in Bengal before making international waves.

Advertisement

In the thirty-seven years thereafter, Ray would experiment with new themes and styles, rolling out over twenty-eight feature films and about seven documentaries and short films, and continually extend the frontiers of cinema till death intervened. Making films that were authentically rooted to soil and yet so artistic, he singularly ensured international recognition for Indian cinema.

Behind his outpourings of a class that remained almost undimmed, was his belief that cinema is the highest form of commercial art. Ray was fond of the great Hollywood masters, and never encouraged the ‘arty-arty’ film-makers with no audience focus and scant responsibility to get the financier’s money back. The director expresses himself with other’s money and for him to remain creative, has to understand his primary audience and devise means within available resources, to reach that audience.

Ray, therefore, exercised control over every aspect of filmmaking ~ scripting, acting, editing, scoring music and even handling the camera, while introducing new faces like Soumitra Chatterjee, Sharmila Tagore and Aparna Sen.

Consequently, his films ended up as finished products of art with no place for slack and shoddiness. He was criticised for not taking the narrative risks that others like Fellini, Godard or Bergman had. Keeping his audience in mind, Ray kept the story at a simple level for everyone to follow, and enriched it with layers of psychological inflections for the more sophisticated to savour.

In the process, Ray devised a model that has inspired directors of all hues ~ especially in India where regional richness deserves to be celebrated. Indian cinema is said to have come of age with Pather Panchali, in terms of its quality and impact. Introducing fluidity of images, distinct from the type of photographed theatre, and dextrously employing various cinematic means, he developed a new language that could express his imagination in this sensuous medium.

His Apu trilogy, the zamindar films, the Calcutta trilogy, the musical and children’s films and most others were transformational in nature. Public taste and attitude towards movies started changing with them. Cinema suddenly attained respectability and became a subject for serious, even intellectual discourse, like sophisticated literature earlier.

Literate people sought to be cinemate as well. Talented film-makers from different regions started making their mark following Ray’s footsteps. And his influence was not confined to India alone. Ray’s masterpieces are remembered for their technical brilliance, the manner of exploring human conditions, and their compassionate underpinnings. Against the larger forces of history how ordinary men and women cope with life, informs, with irony and humour, much of Ray’s oeuvre.

Characters like a former actor discovering that ‘the throne is there… but I have been overthrown’, or a retired teacher lamenting of injustice in God’s dispensation, play out their daily lives while Ray weaves the complex web of relationship, between man and woman, believer and the sceptic, old and the new. Described often as an aueter, a ‘novelist with a camera’ or a poet in celluloid in the best humanist tradition, Ray once described himself as a story-teller.

A true but modest claim. His earlier films were pure magic, prompting Time magazine’s critic to wonder ‘Will Ray redeem his prodigious promise and become the Shakespeare of the screen?’ Some likened them as the culmination of Neo-realist cinema.

Ray’s later films charted new territories, more direct and perhaps less nuanced in tone, especially when dealing with contemporary problems. But his criticism of authoritarianism, indictment of religious superstitions and of widespread corruption in our lives has never been propagandist. In fact, these works were significant in their departure from the earlier norms that Ray had established, but equally warm and luminous nonetheless. Despite his distinctive stamp, as can be seen, for instance, in Picasso or Hemingway, there was no sameness in Ray’s films.

His ability to discover beauty in the commonplace and dramatic potential in ordinary lives, to transform individual and local experience to the universal, his controlled passion and attention to detail and, finally, truthfulness marked his classics. Memorable shots and sequences with the proverbial Ray-touch are analysed in text books and studied in film schools all over.

No wonder everyone has her own favourites from Ray’s garden! Like the international success of The Apu Trilogy came in the way of appreciating some of his later films, Ray’s consummate artistry as a film-maker has inhibited many from fathoming his contribution to literature, music, and even in designing typefaces ~ Ray Roman, Daphnis, Holiday Script, Bizarre.

His genre of writing with detective Feluda and science-fiction character Professor Shonku has been popular with intelligent readers of all ages. As a complete artist, like Tagore before him, he left his impress on every field he had ventured into. Not surprising that fame and recognition followed him all his life. Every major honour such as the Bharat Ratna and an Academy Award for lifetime achievement came his way. He was awarded doctorates from universities including Oxford and Delhi, and invited to deliver Norton lectures by Harvard University.

French President Mitterrand went to Kolkata to personally decorate him with the Legion of Honor. National Professorship, Fellowships of learned institutions, Phalke award and countless ones from film festivals apart, the UN proposed that he made a film on ‘the horrors & miseries of war’ for worldwide TV screening. Interestingly, his admirers included the notables from Bollywood to Hollywood.

Kurosawa’s description ‘It is the kind of cinema that flows with the serenity or nobility of a big river’ sums it up all. But no praise or criticism affected Ray’s composure and dented his undying spirit. He remained busy at his Kolkata flat doing what he loved most, and perhaps made the world a little better place to live in. For our cultural nourishment, we owe a great deal to Ray.

The birth centenary of this tall man who, by global standards, set gold standards in cinema, and contributed significantly to other arts, is an occasion to reflect on his legacy and see that his work reaches a wider audience and an expanding readership, especially in our country.

The writer is a former Indian Administrative Service officer who also worked in the private sector and with the UNDP.

Advertisement