A caste count may, on the face of it, appear to be a swingback to an antediluvian social construct, but “shining India’s” chattering class must realise that a caste-based census is a reflection of social reality 90 years after a similar enumeration. Strangely, there can be no obfuscation of that reality. It is a critical factor that continues to determine State Policy 70 years after the adoption of the Constitution. Castes remain a major underpinning of public policy, most importantly in the spheres of education and employment. In fact, it forms the foundation of the entire reservation concept in independent India.

The simple argument in favour of caste enumeration in a country professedly aspiring to a casteless society would be the better targeting of social justice policies. This can only be done by matching caste with the socio-economic, demographic and educational data recorded in the census. Some social scientists have tried to make a virtue of a necessity and argued that the more data we have the better it would be for research and analysis. It does not require great wisdom to say that if OBC figures are based on the 1931 census, the reservation policy per se does not have a valid foundation. Jobs have been earmarked without a data base. The primary objective of a census operation is to update the database, after all. It reflects the structure of the population; the electoral constituency is of secondary importance.

Advertisement

The enumeration, classification and ranking of castes became an important part of census operation under colonial rule. Colonial civil servants, such as H H Risley and J H Hutton, both census commissioners in their time, were notable anthropologists. However, the societal structure has not actually changed from 1931~when the last caste-based census was conducted – to 2021. On the contrary, it has been reinforced and on occasion, violently so, unlike in British India. A casteless society still remains a utopia ~ sections of civil society are no less caste conscious, if not as barbarous in their attitudes as the khap panchayats sometimes.

An important element of census operations of the British colonial rulers was enumeration and classification of caste. It was the realisation of the divisive uses of caste census that made the first government of independent India do away with caste from the 1951 census onwards. Such a proposal came up before the 2001 census during the National Democratic Alliance government also but Atal Behari Vajpayee and Lal Krishna Advani did not allow coalition dharma to make any compromises on national unity.

However, the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance, ignoring the stand taken by leaders like Motilal Nehru and Jawaharlal Nehru, CR Das, Gokhale and Patel in making India a nation of citizens of equal rights, caved in to the demand of some of its coalition partners.

The Directive Principles in the Constitution say the State shall strive to minimize the inequalities in income and endeavor to eliminate inequalities in status, facilities and opportunities, not only among individuals but also among groups of people residing in different areas or engaged in different vocations. In order to enable this, the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes have been given 15 and 7 per cent reservation respectively in government jobs and admission to educational institutions.

Article 340 of the Constitution mandates the government to promote the welfare of Other Backward Classes. The first Backward Classes Commission headed by Kaka Kalekar identified 2,399 castes as backward and 837 among them as the most backward. His recommendation, however, was that backwardness should be determined by criteria other than caste.

The second Backward Classes Commission headed by Mandal declared 52 per cent of the population as OBC. Since the Supreme Court had put a ceiling of 50 per cent on reservations, the OBCs received 27 per cent except in Tamil Nadu which already had 69 per cent reservation and was allowed to continue it. Naturally, OBC enumeration should have begun in 2001, in the first census after OBC reservation came into effect as national policy in the 1990s.

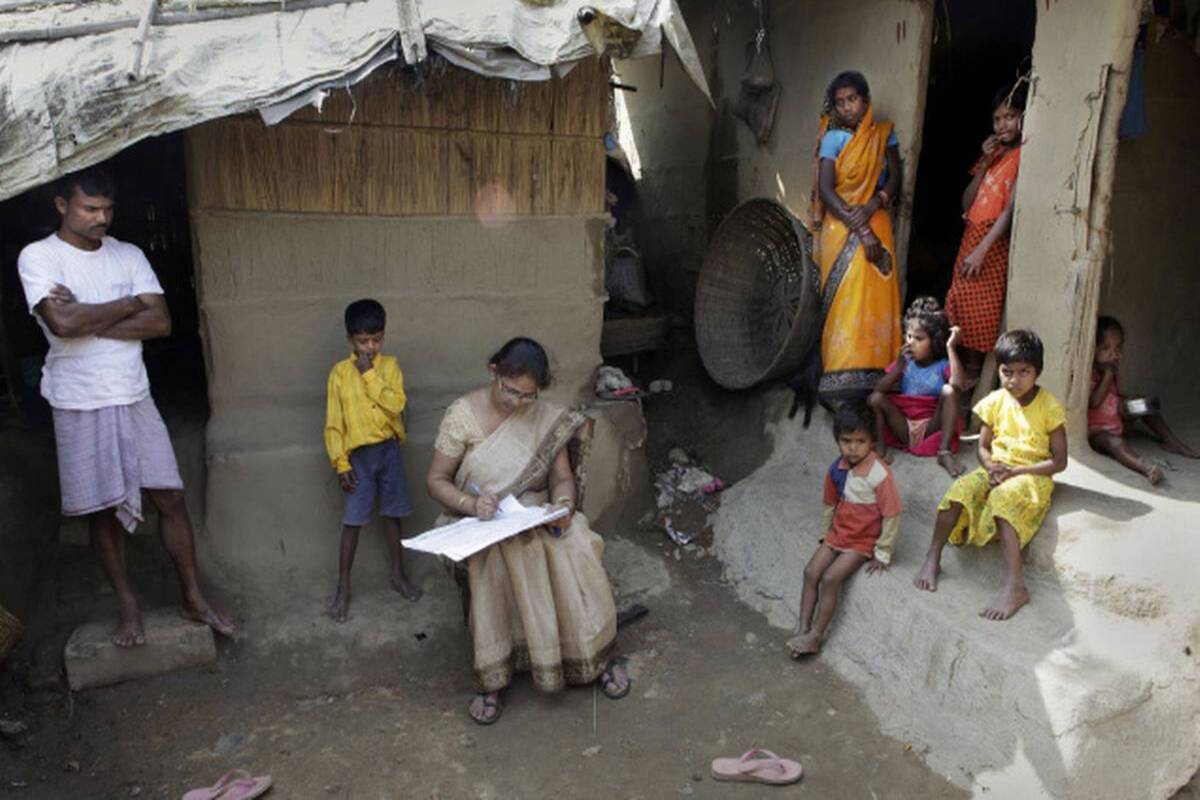

Since the critics of census enumeration consider it not quite useful enough for a comprehensive understanding of a complex society, the Socio-Economic and Caste census was conducted in 2011. Whereas the census provided a comprehensive picture of the Indian population, the SECC came to be a tool for identifying beneficiaries of state support. A Socio-Economic economic caste census was conducted to get data on the caste and economic status of every household in the country, which was made public in 2015, but the caste data was withheld citing discrepancies. The 2011 caste-based census was to provide the government with at least an approximate database.

The importance of such data is crucial not least because public policy cannot be formulated on the basis of an indeterminate group. And amazingly enough, this precisely has been the praxis since 1947. Small wonder that planning techniques ~ in absence of a clue of the dimension of the target group ~ have as often as not gone awry.

The demand for OBC enumeration has been endorsed by the National Commission on Backward Classes, the Parliamentary Committee on the Welfare of OBCs and, in the past, by the Registration General of Census. The Chief Minister of Bihar and Union Minister Ramdas Athawale are among those who have supported the demand. More recently, such demands have come from the BJP National Secretary Pankaja Munde and the Maharashtra Assembly as well. A writ petition filed by an individual from Hyderabad is pending in the Supreme Court which issued notices in February 2021.

It sounds legitimate that a caste census would bring to the fore the numbers of individuals who are on the fringes ~ which should be of much use in democratic policy making. It has been argued that a Socio-Economic caste census would be the most effective method to justify reservation based on evidence. In absence of such enumeration, there is no proper estimate for the OBC population as also various groups within the OBCs.

It may be remembered that the Mandal Commission’s estimate of 52 per cent OBC population is based on the National Sample Survey.

A caste census would bring to light the number of marginalized people or the kind of occupations they pursue, which may be in consonance with the court directives to have adequate caste data in regard to reservation.

To do away with the idea of caste being applicable to only disadvantaged and poor people, caste enumeration will serve as a source of privilege in society. Myths of caste elitism may be debunked through a caste census.

The structure of wealth distribution in our country in various studies shows the hierarchy of the caste structure. To bridge increasing inequalities, caste-based data is necessary. It is well known that upper caste groups have been the primary beneficiaries of the developmental policies of the government. Since caste census can reveal the income and educational gaps between upper and non-upper caste groups, the former suffers from an apprehension that the 50 per cent ceiling on reservation might be broken, which they fear as an assault on their economic prospects.

As early as the 1940s, WWM Yeatts, the Census Commissioner for India for the 1941 census, had pointed out that “the census is a large, immensely powerful, but blunt instrument unsuited for specialized inquiry”. It is time we make it suit our requirements. The quota regime will make an updated caste count imperative and public policy, such as it is, makes this an administrative prerequisite. It would be irresponsible to lend a political spin to a caste-based census.