When Santals go abroad

Reflections on an intercultural experiment where representatives from the tribe travelled to Germany

(Photo: Facebook)

The Santhal writer, Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar (HSS), has been accused of pornography by a group of educated people who are mostly Santhals themselves.

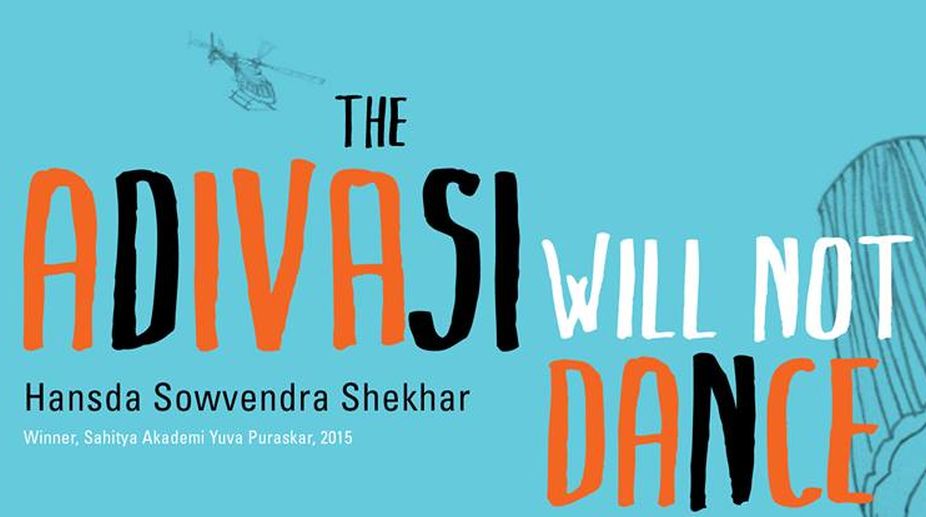

They object to him giving Santhal society a ‘bad name’ through his writing, especially to Santhal women. This campaign has brought to light that the two books that HSS has so far published ~ The Mysterious Ailment of Rupi Baskey and The Adivasi Will Not Dance ~ may have objectionable content. Before that, his books had earned praise and prizes. The author has attended a number of literary festivals and was talked about as a literary discovery.

Advertisement

As far as I can see, he is the only Santhal author who has written about his own society in English and got published by a highly respected publisher, Speaking Tiger, which has an all-India, perhaps global, distribution network. But instead of being proud and content that a writer of their own community had ‘arrived’ as a mainstream writer, the educated Santhals reacted against him. In this article, I will refrain from taking sides pro or contra the author or the campaigners.

Advertisement

All I wish to accomplish here is to raise a few issues which I fear have not been stated sufficiently and have not been duly considered. HSS’s second book has, meanwhile, been banned by the government of Jharkhand. He has been, according to newspaper reports, suspended from his government job as a medical doctor in Jharkhand, and he has been threatened with a law suit. It is extraordinarily difficult to ‘prove’ whether a piece of erotic literature is pornographic or not. Literary history is replete with public accusations of famous and not-so-famous novels or stories and their authors.

Many of these literary works have survived the turmoil of their day and are meanwhile acclaimed and read as classics of literature. Remember Fanny Hill by John Cleland or the works of D.H. Lawrence and Henry Miller to name but a few prominent examples. Pornography is difficult to ‘prove’ because one must never consider the passages that are being objected to in isolation. The entire opus needs to be read and the objectionable passage understood in the context of the entire work.

The question to be asked is: Are these passages indispensable for the understanding and appreciation of the entire work of literature? Do they carry a social or aesthetic or moral message which is integral to the entire work? Or are they embedded in the narrative in order to attract readers to a particular book, that is, for arousing sexual lust, for financial gain or any other extra-literary purpose?

To prove this, needs careful reading. One famous example from cinema comes to mind. The film, Bandit Queen, had a brief shot depicting frontal female nudity to which the censors objected. The director explained that the shot is vital to make the brutal shaming of Phoolan Devi by the landlords horribly clear. In the same way it must be decided with sober maturity whether or not the passages declared as ‘pornographic’ are irrevocably needed to exemplify the exploitation of Santhal women.

Some critics of the campaign have stated that the passages in question make painful reading exposing the plight of women in rural society. Literature, let us be clear, has the right and duty to depict all of reality, not shying away from its brutal edges.

This is a literary consideration which, honestly, is the only valid consideration in a society of mature, responsible readers. In India, there have been other considerations as perhaps society does not consider its readers mature and responsible enough to accept literature as what it is. The principal extra-literary consideration is whether a particular piece of writing may incite social tension possibly leading to the loss of peace and amity within society.

India has a history of book-banning, right from Salman Rushie’s Satanic Verses onwards, in which such considerations have been cited. In the case at hand, the book The Adivasi Will Not Dance was already available in the market for about two years.

The general reading public did not object to it; in fact it earned critical praise in mainstream newspapers. I am not aware of any social reaction against it, even though I hear that the campaign by Santhals against HSS’s writing had begun already in 2015.

Hence, the campaign itself has gained the potentiality of creating an upheaval, after HSS’s writing was declared ‘pornographic’. The methods employed, like burning an effigy of the writer, are noticeably designed to arouse passion. The campaigners have the satisfaction of having the book banned in Jharkhand, while it presumably can be sold and read in Kolkata and elsewhere outside the state of Jharkhand. Typically, it may now get more readers who buy the book out of curiosity.

The campaigners wrote and spoke as representatives of their own community. Freedom of expression allows them to approach the general public in such a manner. But, probing more deeply, the question remains what gives them the moral authority to speak as the voice of a whole community.

Is there any organization behind them which has a popular base? Have they been selected or elected by such an organization? Or do they indeed speak merely as individuals? If so, this needs to be clearly stated, or the organization on whose behalf they speak, named and characterized.

It is fraught with complicated social, moral and in this case literary implications to make oneself the mouthpiece of a community. Certainly, education alone cannot authorize a person to speak on behalf of a large group.

Even for authors it is problematic to make themselves the representatives of their community in their writing. Obviously, they are free to depict their own community, the one with which they are most familiar with. But fiction will always deal with individuals and the depiction of their lives in concrete situations. One may derive the outlines of a group character from these narratives, but this is not the writer’s immediate intention.

There is one last concern which is of a more personal nature. One educated Santhal friend of mine pointed out to me that conflicts in Santhal villages are generally resolved through discussion in which the entire adult village population participates (unfortunately, so far, only the male members are called). I have myself sat through such meetings in a village at some distance from Santiniketan. They may drag on through half of the night, but they will generally conclude with a peaceful, consensual solution.

This talent for conflict resolution is admirable. Why, I ask myself, does this spirit not pervade the present conflict? Instead, what I hear being said now is that a witch-hunt is being orchestrated against an author who chooses to be different.

The social evil of witch-hunting with which Santhal society has been stigmatized in the public mind is being resurrected. This is very painful to see.

(The writer has worked with Santhals in the area of education for the last thirty years. He can be reached at martin.kaempchen2013 @gmail.com)

Advertisement