The sheer magnetism of the black and white painting that hung on the walls of National Gallery of Modern Art left the visitors in amazement. Powerful in its simplicity, it consisted of a white circle on a black background with white strokes emanating from it. This minimalist work was the marvelous creation of a Paris-based artist. Educated mostly by upper-caste Hindus, Syed Haider Raza was immersed in the Ramayana and Bhagavad Gita as a young boy, from which he derived some of his most significant ideas and inspirations for his work that led to the emergence of the very famous Bindu Series.

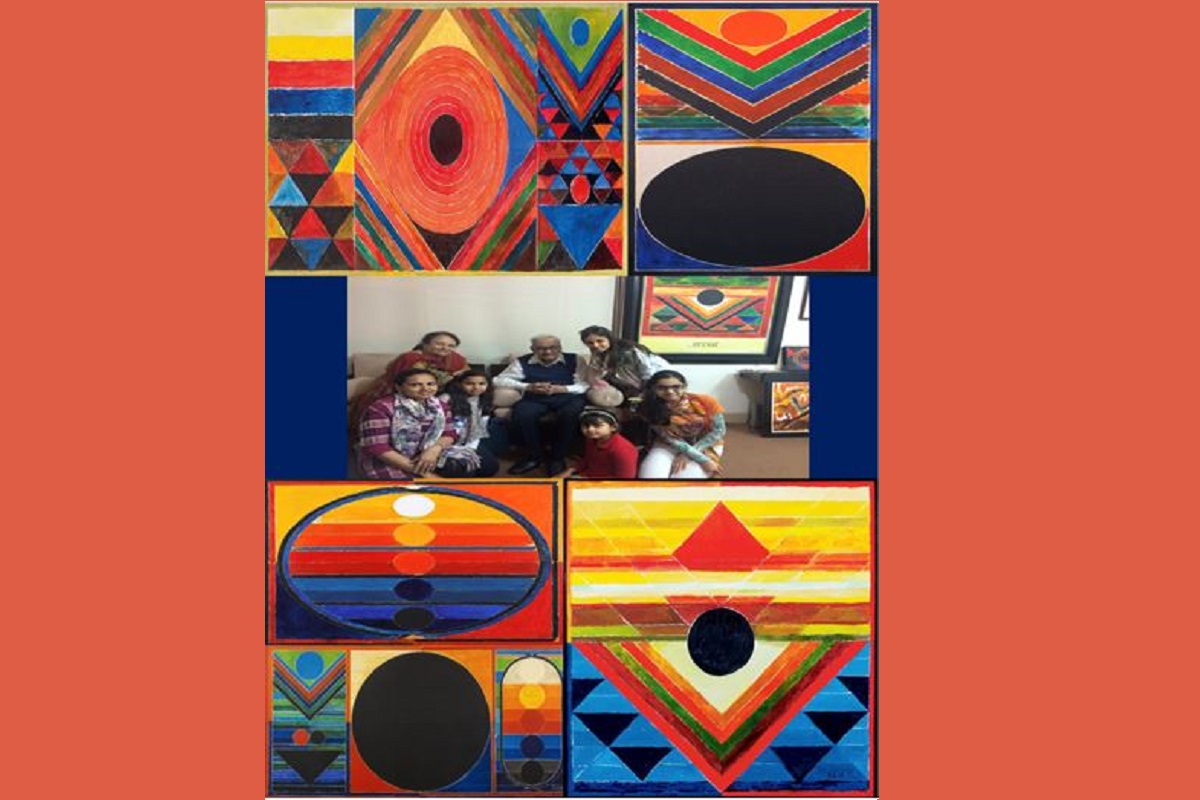

When I met him with my family on the 20th of February 2015, he was wheelchair-bound, as he had been for many years, sipping a glass of wine and chatting convivially with us. Sitting amidst a body of work, which he called the Bindu Series, Raza vividly spoke of his childhood. Conversing with him for over two hours, I learnt quite a lot about his life and journey as one of the most renowned artists that the 20th century had ever produced. The aura of greatness that he embodied had touched my young mind irrevocably.

Advertisement

He was born in 1922 in Babaria, Mandla (a district area in Madhya Pradesh), to Sayed Mohammed Razi, the Deputy Forest Ranger of the district and Tahira Begum. Raza took to drawing at the age of 12. As a boy of 13, he moved to Damoh, and completed his school education. As written by Atul Dodiya, Raza had his first solo show in 1946 at the Bombay Art Society Salon, and was awarded the Silver Medal.

Meera Menezes in her piece ‘S.H Raza, Artist Who Showed the Universe in a Single Bindu’ says that, for Raza, black was the mother of all colors – the point from where all energy in the universe emanated and into which it also converged. He had an odd sort of connection with the color black, where he felt that it had colossal potential, the contending powers of light and dark. This could be revealed in a perception of new imagery and a creation of a new language. Who could have imagined that a young lad born on February 22, 1922, in a forest village would later conquer Indian contemporary art onto the global stage?

Raza’s abstract works are mired in memories of his initial years spent in the sylvan forests, connected to nature. His collection of work began with realistic landscapes in France. As time passed, his style evolved into abstraction. He later started with a firm abandonment of the figuration, giving way to the emergence of the Bindu or circle.

On asking Raza about what attracted him to a simple circle, he gave immense credit to his teachers as having a great influence on him. Especially his headmaster who, at the age of nine taught him to calm his restless spirit and mind by meditating on one point, which he drew on the wall. For him, the most significant form was a point which could be expanded to a circle; a circle which could be divided by two lines, horizontal and vertical; as the intersection of these two lines created energy. These lines have the power to develop in the most natural way of multitude of forms, first with the intersection of black and white; and later, with energy, where colors develop.

The Bindu, according to Raza, signified the rise of the momentousness of spirituality. Variously interpreted as shunya or the void of nothingness in his works, it also served as a symbol of the seed which encapsulates the prospective to give birth to all life and is the focal point of both energy and creativity. Just as you could visualize Husain by seeing paintings of those iconic horses, you could easily visualize Raza by the ubiquitous presence of the Bindu. While Raza’s obsession with the Bindu gave his series an unarguable Indian flavor and authenticity, his interest in abstraction put him in a league with the masters of European modernism — with Wassily Kandinsky or Kazimir Malevich, to name a few. As a result, Raza would always hold a special meaning in the hearts of people of all sorts: Indians, Europeans, spiritualists, traditionalists and even hedonists, who relish the vastness and a unique essence with his choice of colors.

Amidst the vibe of his gallery, surrounded by paintings, more than a dozen brushes, watercolors, acrylic and oil pastels at every little nook and corner, the one thing that stood out in his work was his perspective of looking at the world. He was skilled a mastermind who had an original, legitimate way of putting out his raw ideas on canvas using distinct means like pencil, oil and water color for the world to luxuriate in. In him there was self-confidence culminated with humility- between colors and the inherent spirituality, there was a relaxed dialogue. The zero in Raza is a virtue not of its minimal nature but its vast energy and simplicity. He was a unique artist who listened to the primordial sound which provided color-visibility to each and every member of the audience.

From the woods of his childhood until he breathed his last, Raza pursued the sacred on his canvases by expressing to his audiences all that could not be spoken. His series addressed an assortment of themes ranging from social issues, spirituality, religion and perception. Each time he sat down to paint,“he faced a blank canvas, with a prayer in his heart and brush in his hand ready for the next encounter and challenge that was thrown upon him” (“Yet Again: A Tome on Modern Indian Artist S.H Raza”). This is what made him profusely special.

Raza was deeply influenced by the rich vibrancy and multiplicity of colorfulness of Indian life and nature. In all his paintings in the series, the lines were not straight. In his paintings, “geometrical configurations and the lines are like tree-leaves. They also quiver like leaves” (Passion: Life and Art of Raza). In other words, the lines in all his work were not perfectly straight, they were drawn without lifting the pencil and looked as natural as tree leaves. As a painter, Raza is known not for his lines, but the use of vibrant colors in the background of the Bindu series. In most of the paintings in the series, the Bindu or circle was black. This implied the central force of energy that pulls out negativity and spreads positive energy all around. These colors do not lie looped under the layers; they are alive, vibrant and restive.

Considering the first painting in the Bindu series, Raza said that he was shifting to pure geometry, towards the plain white canvas. This approach to simplicity and to reach back to the original form was not easily perceptible like that of the leaves. His concept became fiercely entrenched in his work in the form of geometric abstraction, one being, the progression and evolution of humankind. This was a means through which he decided to creatively showcase all that existed in the world we currently live in.

In his perspective, we are able to witness the entire spectrum of color, from agony to withdrawal. Fascinating is that even when he applied colors that to a layman’s eye, who had no idea of the arts, it looked the same as on a palette, there was always a timbre so masterfully achieved on the canvas, shown by each line separated by a variety of different colors. Each stroke of the paintbrush, implied that the colors were beautifully merged and thoughtfully chosen. And when I asked how he decided what colors to juxtapose alongside one another, he smilingly said that it just happened to him naturally; more like a practiced dancer whose feet just simply struck to the floor in rhythm instinctively.

Raza casually expressed how preferred to be left alone when he was to paint. This time of his which he chose to spend by himself also reflected in his work- not only in the lines and the colors, the artist was now peacefully the portrayal of himself: there was no trace on another soul. This, helped him think and connect deeper, get newer ideas and focus on his own unique creations. In the Bindu Series, there is a certain void in his art- not as a withdrawal from energy but as its radiation. In the words of Ajneya, “all creation is merely grateful acceptance”.

On telling Raza about my love for art, colors and the paintbrush, the first thing he told me was, “be connected to your roots, when you paint, express yourself, be original, respect the brush and it will, in return respect you”. These words of his still echo in my ears each time I hold the flat-bristled brush in my hand. In him, I saw a man for whom art was not just inspiration, expression and instinct, but hard work, tons of hard work, determination, grit, perseverance and passion. He further added, “Explain your work. You don’t need to convince anyone about your art, but communicate your ideas clearly”. After his final return to India the distance between living and painting dwindled and slowly disappeared: he started living to paint, and painting to live. As expressed by the artist’s close friend and author, Ashok Vajpeyi, Raza’s life mission was to pursue his art; a whole life dedicated only to art. For him, I feel, art was an unrivaled human accomplishment and he practiced for nearly seventy-five years, with truthfulness, passion and humility.

Leaving his artistic language aside, another thing that manifested through him was the outstanding amount of faith he had in his work. This is reflected in his favorite quote, “Maano toh shankar, na maano toh kankar”; to one who has faith, a stone can represent God and to one who doesn’t, it is a mere stone. This faith and belief were grounded in his strong ties with his birthplace, India, where he felt a unique connect.

In 2001, Raza created the Raza Foundation to support young artists in India. It began by felicitating young Indian artists, beginning with two awards annually, one in visual arts and one in poetry. Classical music and dance were later added to the list of awards as well. Some of the best, the most promising, innovative and daring artists, poets, musicians and dancers have been recipients of these highly coveted and prestigious honors.

Vajpeyi further adds that Raza would visit temples, churches and mosques regularly, and yet was never absorbed by ritualism of any kind. In times of widespread disbelief, he emphasized deeply on the importance of belief for creativity and imagination. He used to fold his hands in salutation before he finished working on a canvas. In a deeper sense, his art was his ultimate religion.

He left a legacy of courage, vibrant imagination, nobility, humility and unfailing generosity that is missed by each one of us. Through his art, he touched eternity. His ideas of perception, expression and evaluation is still greatly valued by all today.

(Saanya Jain is currently in her third year, studying at O.P Jindal Global University’s School of Liberal Arts and Humanities. An alumni of Delhi Public School, R.K Puram, she is pursuing a self-designed major in International Business and Psychology).