BJP likely to name next Delhi CM only after PM Modi’s return from US

The BJP is likely to name the next Chief Minister of Delhi anytime after Prime Minister Narendra Modi returns from his five-day visit to France and the United States.

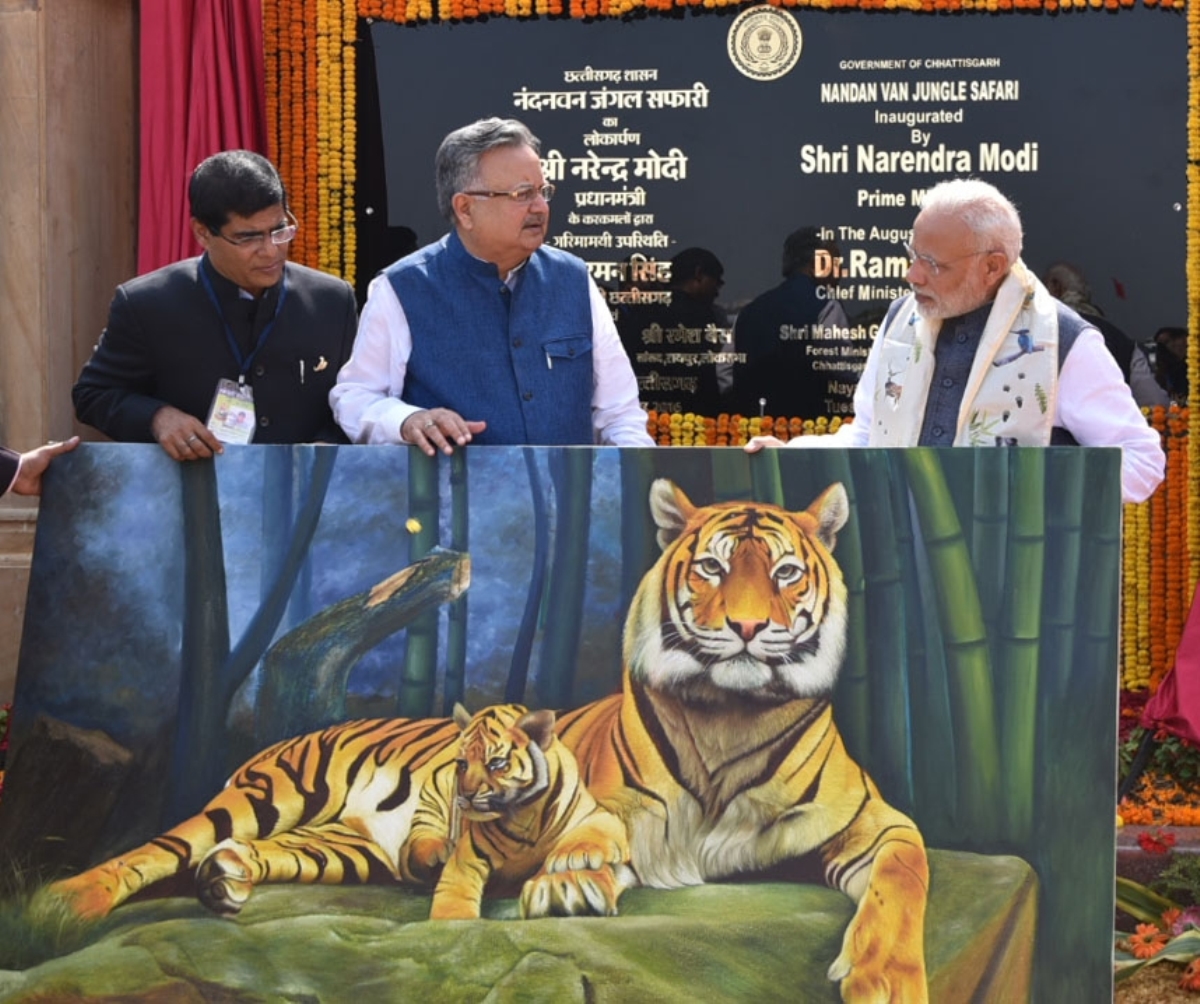

While managing well the developmental concerns of his state and the Maoist problem, Raman Singh has maintained the Bharatiya Janata Party’s hold on Chhattisgarh for 15 years.

(Photo: IANS)

Chhattisgarh Chief Minister Raman Singh will be looking for another five-year term in the central Indian state beset by Naxal violence that has left thousands dead over the years. Singh, 66, has held the top job in Chhattisgarh since 7 December 2003, when his party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), won only the second assembly election in the state.

By longevity of rule, Singh is currently at the 15th place in the list of longest-reigning chief ministers of India. Should he win the election and continue for another five years, he will jump seven places to eighth.

Advertisement

The rise to power

Advertisement

Born on 15 October 1952 to Vighnaharan Singh Thakur and Sudha Singh, Raman Singh graduated in Ayurvedic Medicine (BAMS) from Government Ayurvedic College at Raipur after studying science in Government Science College, Bemetara from 1971 to 1972.

Following a brief stint as a doctor, during which he often treated patients for free, Singh embarked on his political journey in 1980s from his birthplace, Kawardha, which is now a municipal city in Kabirdham district of Chhattisgarh.

A member of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) and subsequently BJP since the very beginning, Singh first became an MLA when he won the Kawardha constituency in the 1990 Madhya Pradesh assembly elections. (Chhattisgarh was then a part of MP.) In 1993, he again won from the same seat even though the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) lost the elections to the Congress. In the tumultuous political years in then Madhya Pradesh, Singh lost the 1998 assembly elections to Congress’ Yogeshwar Raj Singh.

But Singh’s political career took another sharp rise to the north, quite literally. In 1999 he won the Rajnandgaon Lok Sabha seat to become a Member of Parliament. Singh was made the Union Minister of State for Commerce and Industry in the government led by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. He served the position till 2003, when he was redeployed in Chhattisgarh just ahead of the state’s second legislative elections.

While the Congress had won the very first elections in the state, Singh, who was the state party chief of Chhattisgarh, gave the BJP a resounding victory by grabbing 50 seats in the 90-member assembly in the second Assembly elections. Singh would go on to lead the BJP for two more successive terms in the state, with only slight differences in the mandate. In the 2008 elections, the BJP won 50 seats once again, and 49 in 2013. (In the three elections, the Congress – the main opposition in the state – saw its fortunes rise from 37 to 39.) In the process of making BJP the power in Chhattisgarh, Singh turned Rajnandgaon into his bastion. A five-time MLA, he won from this seat in the last two assembly elections, besides representing it as an MP in the Lok Sabha.

Development, the priority

Fifteen years is a really long time in the top job, especially when you are the chief minister of a state that is infamous as the heart of India’s biggest internal security problem – a thorn in the development of the region and districts around it. Eight of the 15 worst Naxal attacks in the country since 2008 have taken place in Chhattisgarh – five of which were in Sukma in Bastar region. Thus, nothing in Chhattisgarh is more important than development of the state and the elimination of the Naxals.

A major reason behind Singh’s continuous success is his focus on development of the state and effectively tackling the Naxal threat while coordinating with whosoever is at the Centre.

While the state enjoys the special focus of the Centre, in part due to its notoriety as a hotbed of Naxal terrorism, Singh has himself backed major projects in an attempt that development reaches the remotest parts of his state.

For instance, in 2006-07, Chhattisgarh was the first to implement a 20-point developmental programme of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Today, Chhattisgarh can boast of surplus electricity and a very effective Public Distribution System (PDS). It has also steadily attracted investment as well as Centre’s assistance in the form of funds. According to a report, the state received 26 per cent more funds from the Centre in 2016-17 than it did in 2015-16.

But in spite of all these advantages, the state still has the fifth-highest number of poor in India. Despite the rising industrial footprint, the number of factory jobs are yet to move on an equivalent pace. And like some other states in India, farmers in Chhattisgarh, too, have their own concerns regarding farm produce and farm income, which is among the lowest in the country.

Raman Singh, however, says that schemes such as Lok Suraj Abhiyan, Gram Suraj Abhiyan and Vikas Yatra have helped addressed the grievances of people who had complaints against local officials. Rejecting any talk of anti-incumbency, Singh asserts that the people have no complaints against the state government.

Another advantage for Raman Singh is in the form of the BJP-led NDA government at the Centre.

Development of Chhattisgarh is also high on the Centre’s list of plans for the state. Chhattisgarh, with Centre’s assistance, is steadily building roads, electrical infrastructure and creating other necessary resources to augment the state’s growth rate. Recently, Prime Minister Narendra Modi was asked by a party worker from Mahasamund about the BJP’s political agenda for the upcoming elections. Modi said, “We have three, the first is development, the second is faster development and the third is development for all. These are our only agenda.” The PM was not speaking in the void. In April this year, he launched the pilot run of the government’s ambitious Ayushman Bharat Yojna from 1,033 hospitals in Chhattisgarh.

Even NITI Ayog’s developmental plan for Northeastern and eastern states of the country includes 10 districts of Chhattisgarh for urgent development. Dubbed ‘aspirational districts’, the districts will receive special attention for overall developmental purpose.

Among the districts earmarked by NITI Ayong is Rajnandgaon, which has the CM’s constituency. The others are Bastar, Bijapur, Dantewada, Kanker, Kondagaon, Narayanpur, Sukma, Korba, and Mahasamund. Barring three – Korba (Bilaspur division), Mahasamund (Raipur division) and Rajnandgaon (Durg division) – all other districts are in Bastar division, which is the centre of the Red Corridor and the heart of Naxal violence in the state.

Thus besides development, ending Naxal violence has always been high on the agenda of any government at the Centre or the state.

Naxal, the problem

On 27 October 2018, the day Raman Singh embarked on his poll campaigning, Naxals killed four CRPF men in Bijapur district of Bastar region. But the killing of a Doordarshan cameraman and three policemen on 30 October 2018 in Dantewada – just two weeks before the first phase of the elections in the state begin – sent across a much more chilling signal of the gravity of Maoist violence in the state.

Clearly aware of the situation in Bastar, Singh had in August this year asserted that the region’s face was changing from that of a violence-riddled land to a “model for aspirational districts” of the state. In July this year, President Ram Nath Kovind, too, had praised Raman Singh government’s efforts to bring in a change in the lives of tribals of Bastar region. Singh has so far, again with help from the Centre, handled the Naxal problem deftly.

Bastar, from where this year’s assembly elections will begin, is a 40,000 sq km area rich in iron-ore. The tribal-dominated and heavily-forested region has 12 assembly seats. Over 55,000 paramilitary troopers and 25,000 state policemen are busy fighting the Naxals, whose top commanders have been using the treacherous terrain as hideouts since 1980s.

As a contest, Raman Singh has a tough fight this year. Even though he claims that there is no anti-incumbency, the vote percentage difference in the 2013 elections between the BJP and the Congress was less than one per cent. This year, however, the fight could be tougher as former Congress leader and the state’s first Chief Minister, Ajit Jogi, is bringing his newly-formed party, Janta Congress Chhattisgarh (JCC), for a three-cornered contest. Jogi, himself an influential leader, poses not only a serious threat to Congress’ chances in the state but also an opportunity for a Karnataka-like alliance in case of a hung verdict. (He has already joined hands with Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party.)

But even though the word ‘equation’ is often used in poll commentaries and analyses, elections are not pure mathematics where an outcome can be calculated with the precision of a decimal.

On 25 May 2013, Naxals killed almost the entire top brass of the Congress leadership in a daring attack in Darbha valley. Former state home minister Mahendra Karma, the founder of anti-Naxal squad Salwa Judum, senior Congress leaders Vidya Charan Shukla, Uday Mudaliar, and Nand Kumar Patel were among 27 people killed in the ambush. Raman Singh had then accepted that there was a security lapse which led to the attack on the Congress leaders.

At the time, many predicted that the BJP will be voted out of power. Yet Raman Singh returned to power for the third term and is now gearing up for a fourth.

Advertisement