Terrorism is one of the biggest problems that the world is confronting today. The international community is making every effort to combat this menace. Then there are climate change issues, economic crises, political instabilities etc.

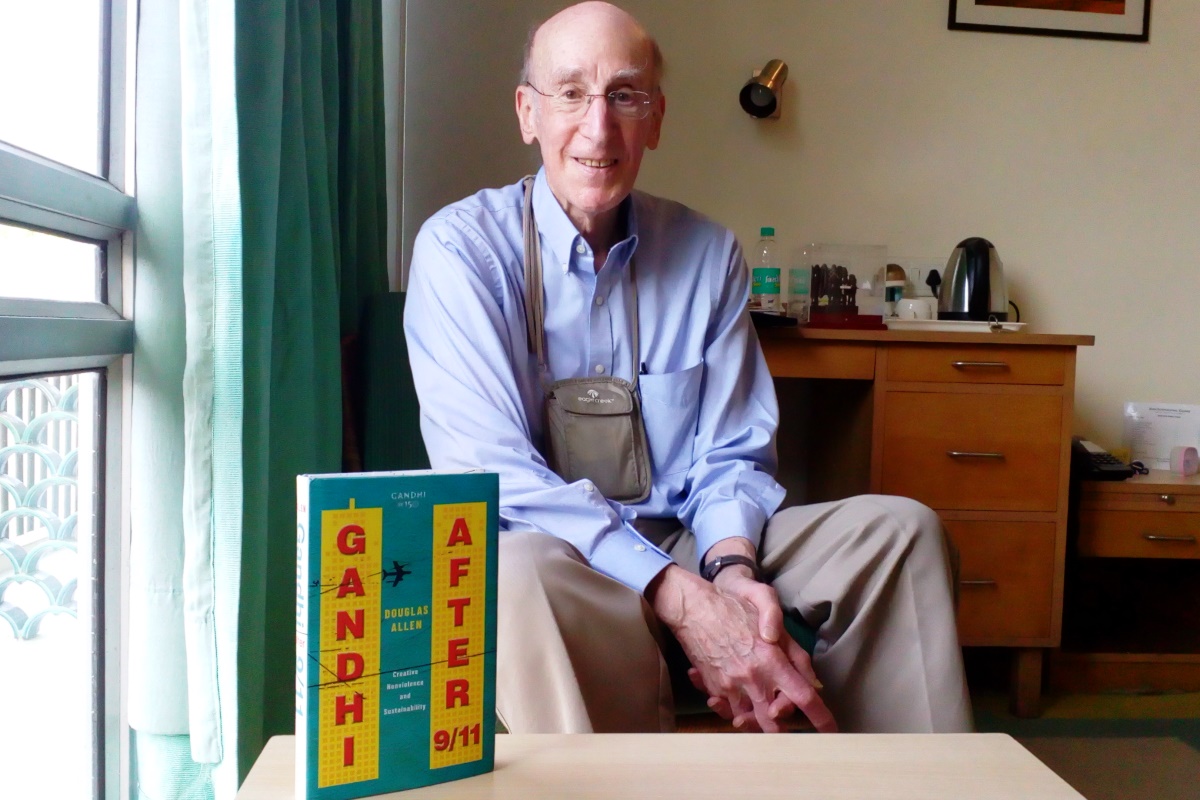

A solution to these problems could be Mahatma Gandhi, says Professor Douglas Allen, considered one of the world’s leading scholars on Gandhian philosophy, in his new book Gandhi After 9/11. Prof Allen, who teaches Philosophy at the University of Maine, the US, is of the belief that we must look to Gandhi even if “selectively” and “creatively” for a sustainable and non-violent future.

Advertisement

In a conversation with thestatesman.com, Prof Allen dives in great detail on how Gandhi should be seen by us. He gives us a new insight into the India-Pakistan problem from a Gandhian perspective and why Bapu’s ideology is not Utopian.

Prof Allen addressed the United Nations General Assembly on 2 October 2017 on the International Day of Non-Violence. From a Gandhian point of view, Prof Allen explores the perils of capitalism, the appropriation of Mahatma by the same forces who he was critical of, and his understanding of the Bhagavad Gita. At the same time, he explains why Gandhi is more relevant today even if he was imperfect.

What is your book, Gandhi After 9/11, all about?

The title was actually selected by the editors at Oxford University Press. The sub-title was mine, which is ‘creative non-violence and sustainability’. It is a very good title because it has several meanings. One of which is that Gandhi [lived] before 9/11 [WTC terror attack] and 26/11 [Mumbai terror attack] and we now live in a different world. Is Gandhi significant or irrelevant to 21st century? What does it mean for us to live in a world after 9/11? We live in this age of technology. Gandhi wrote about technology and modern civilisation. We live in a world of not just capitalism but also the domination of financial, industrial, corporate, media capitalisation. What would globalisation look like from a Gandhian perspective? These are the things that I try to deal with in the book.

Gandhi did not have a blueprint that gives us all the solutions. He was a great human being. But Gandhi made many mistakes. Some were so big that he called them ‘Himalayan blunders’.

In Gandhi After 9/11, we find that Gandhi doesn’t have all the answers. We can learn some things from Gandhi but then we are involved with these experiments with truth in our own minds. In many cases we have to go beyond Gandhi.

Why pick 9/11? Do you think it was the most climacteric event?

India has faced terrorism in the past. But most Americans believe that 9/11 changed everything for the United States. I don’t totally agree with that because if you are an African-American and look at history of slavery, you’d see so many died in the boats that brought them to America. People were enslaved, beaten, and this long history comes down up to the present time. I work with American Indians [Native Americans]. They have faced genocide. Still this narrative of 9/11 changed everything – so it is also important to understand that. In today’s American ideology, we live in a world of terror and must use terror to defeat terror (scoffs). It is ingrained in the minds of some Americans that America is not only exceptional but also the best in the history of the world. And now we have this ideology called ‘America First’. And it is also coming up among Indians now. There is a certain ideology in India called Indian exceptionalism such as this Hindutva. This thought that we Indians, namely Hindus, we are the best – we have the Vedas, finest spiritual books, best social structure and high values. This is India first ideology. To me this is totally opposed to Gandhi’s values. And yet they try to appropriate Gandhi – use him for their own purpose.

Many in India are of the firm belief that it was not Gandhi’s pacifism but the efforts of nationalist leaders such as Subhas Chandra Bose and Britain’s own economic condition after World War II that led to India’s freedom. What is your view on that?

When I visited earlier, some Indians said Gandhi made us weak. They said Gandhi preferred Muslims to Hindus. Now it’s interesting that some of these very people are saying that Gandhi was a great Hindu hero. The head of RSS gave a speech last year and he said we admire Gandhi as a great hero. Hindutva is Gandhi’s philosophy. [RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat’s March 2018 interview to Panchajanya and Observer.] I wonder what is happening because Gandhi was very critical of Hindutva. Yet, I find that there are a lot of people who are appropriating Gandhi.

Why do you think are they appropriating Gandhi?

There are two main groups who are most powerful in India today. One group is modern – more modern than Americans, they know how to make money, how to use media, and are billionaires. They are very good with technology, engineering and medicines. To them, Gandhi is irrelevant. He is a minor irritant, but basically they ignore him.

The second group is people who have political power, who used to be against Gandhi. Why would they find a new purpose in Gandhi? How can they praise Dr BR Ambedkar, who rejected Hinduism and adopted Buddhism? So why are these caste Hindus embracing Ambedkar and Gandhi? My analysis says it has got nothing to do with values of Gandhi. It’s more like Gandhi can be a means to their ends. Gandhi is a revered figure all over the world. He has a good image. But Gandhi would be very critical of what they are doing.

Some believe India’s politics has increasingly moved away from Gandhi’s teachings since Independence. Do you see that distance growing, or is it shrinking?

India has moved away from Gandhi in its politics. When I first came to India in 1963-64, people and all politicians would talk and follow Gandhi’s policy. But even then it was hypocrisy. The way many of them lived their lives was not Gandhian. There were exceptions. But Jawaharlal Nehru, for example, who I met in June 1963, his vision for India was not Gandhi’s. His vision was modernisation; he created the IITs. He had this industrial vision. Yet Nehru had good values because he wanted science and technology to help people. He wanted people to have the knowledge to help raise others. But today, in terms of politics, it is further away from Gandhi, in their values, policies and priorities.

I am more hopeful that India has more potential for development on Gandhian insights than it was 10 or 12 years ago. But my position is that Gandhi’s approach has to be selectively and creatively thought about and is indispensable to deal with problems of our times.

Isn’t Gandhian thought Utopian, sentimentalist and, may I say, not pragmatic in the world of realpolitik?

If you present him as a sentimentalist – I don’t think he is – the people misinterpret Gandhi. And it depends what you mean by Utopian. Gandhi was an idealist but was also a pragmatist. Gandhi was always concerned with primacy of practice. Gandhi had a view of truth – Satya. He said there is a view of absolute truth about non-violence, compassion, pure ethics, pure religion, and pure spiritual. Gandhi said he had glimpses of truth and it would be arrogant to assume that you know the absolute truth. We are simply trying to move from one relative truth to another, better, relative truth but not absolute truth. Gandhi was practical. He had to deal with the real world.

We will talk of terrorism. It is at the centre of India-Pakistan relations. How can Gandhian thought process can help solve this?

Some people say Gandhi believed in turning the other cheek. But was he naïve? If you say to the terrorist ‘kill me’, the terrorist will just kill you and everyone else. This is not Gandhi. He said that 99 per cent of the times when we are violent, we have alternatives. In my interpretation, Gandhi says that you have to use force when there is no non-violent option available. But Gandhi cautioned that if you use violence, do not glorify it. What you do is not great – it’s a horrible thing that you have been forced to do but it is necessary.

Gandhi’s main strength is preventative non-violence. So Gandhi would say [to Pakistan] think about the root causes of terrorism: basic conditions – economic, political, cultural. How do you change those conditions? I agree with Gandhi. If you grow up thinking ‘India is the enemy’ or ‘Pakistan is the enemy’ – if that is your mentality then you can’t deal with the problem. We have to change those conditions [that create violence]. Unless we do that we can’t deal with this problem.

India has extended its hands of friendship and tried to ensure good ties. However, unfortunately, every time things go wrong between India and Pakistan, the problem comes from across the border. Do you think that Pakistan, which too was not untouched by Gandhian philosophy before Partition, has completely discarded Gandhian beliefs?

Yes, this is a problem because Pakistan’s creation was for many reasons. Even Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who was a very complex person, didn’t expect Pakistan to become what it became. He was a secular person but he used religion as a card. Unfortunately, the pro-Gandhi influencers in Pakistan were put in prison. Pakistan developed as a militarily dictatorship. The US supported Pakistan because it didn’t trust the non-aligned bloc of which India was a part. Now, of course, America is supporting India but for other reasons.

There have to be people in Pakistan who have to work to change what is happening between India and Pakistan. The question is: How does India relate to all of this? I have friends who have spent decades working in Kashmir, young people with values. If you just define Pakistan as the enemy then it’s hopeless, but you also have to be mindful of the horrible things that are happening in Pakistan. How can you encourage people [in Pakistan] who are not like that [fundamentalist]? There are Muslims who don’t want an Islam that is so oppressive. They want an Islam that believes in peace. So this is a difficult situation.

Gandhi was a follower of Bhagavad Gita. What can we draw from that?

Bhagavad Gita was Gandhi’s favourite text. I have a full chapter in my book on this. He meditated on it every day. He was a proponent of Ahimsa. But Gita is not non-violent. Gandhi said that we should not ‘take the Gita literally’. The battlefield in the Gita is within you. And you can interpret the Gita that way, which is correct. But my interpretation is that this does not make Gita a gospel of non-violence. We know that in human history allegories and myths are usually very violent. So, mere allegory doesn’t make the Gita non-violent. Those who wrote the epics were profound spiritual and moral teachers but they didn’t believe in non-violence. So, Gandhi, here, is trying to purify the texts to make it more spiritual and ethical for the 20th century. What does the Gita mean for us today? How can we appropriate it in new ways that speak to the problems we have in the contemporary world? Gandhi could use it as part of non-violence.

We see Gandhi’s non-violence his way of fighting against oppression of British rule. And when we see the fight of other freedom fighters, through violence, in the light of Bhagavad Gita, we will find that it, too, was just. Then why did Gandhi oppose their actions?

The Gita has many paths and Gandhi’s favourite path is Karma Yoga. And since Karma Yoga is action oriented, Gandhi believed that you act with an attitude of renunciation in which you fulfil your dharma but renounce attachment to the results. The other freedom fighters said the same thing on fulfilling duty but not non-violently. Karma Yoga by itself does not give you non-violence. You could be a Karma Yogi and your dharma might involve violent struggle for freedom of country. But Gandhi said that the best way to be a Karma Yogi is through fulfilling your duty through non-violence. He is apparently telling the other Indians that you are using violence in the same way British used. If you succeed, you are simply changing British tiger with an Indian tiger. In this way, Indians will oppress other Indians. For Gandhi that is not Swaraj.

But Gandhi was interesting because he allowed some form of violence. Earlier Gandhi used to call off his campaigns if there was violence as in the 1920s. But in 1940s he didn’t call off the campaigns just because some Indians turned to violence. Yet Gandhi argued that non-violence is not just the most ideal but the most effective way to create an India that is egalitarian and really democratic where people have a say.

Do you think that socialism is a viable option for any economy?

Gandhi believed in socialism but he didn’t believe in the socialism where there is too much violence and too much state power. But Gandhi said that capitalism is a system that is inherently violent, based on exploitation; the people who are wealthy have the power to dominate other people.

In my analysis, Gandhi’s economics is egalitarian and really democratic and in which the people who are productive can actually have maximum self-rule. Gandhi believed it is impossible to have democracy with economic inequality. But Gandhi also had to relate to feudal lords, landowners and capitalists – this is controversial because Gandhi was against capitalism and yet they still supported him. Gandhi was of the opinion that we can’t abolish capitalism. He was against wealth accumulation, but wanted to know how we convince capitalists to voluntarily use their skill, capital, science and technology for uplift of the people.

Am I to understand that Gandhi believed that capitalism is better than socialism as long as capitalism does not focus on accumulating wealth?

I have some friends who interpret Gandhi in that way. But I disagree. Gandhi believed that capitalism is an inherently exploitative system. You don’t have a just and egalitarian capitalistic system. Gandhi was of the view that private property is always violent – it doesn’t mean things that you use for your needs. It means a category of power where some people have the property. But he also warned that force cannot be used to remove private property. Yet, later, Gandhi said that we cannot let poor people getting exploited and we may have to use force. This is what is controversial about Gandhi. Even in matters of caste, he reached out to higher castes to give up caste privilege. He was of the view that the only way we can remove caste is if these privileged people renounce it. But the problem is that people with power do not want to give up. Gandhi was also against caste struggle espoused by Karl Marx because he thought class struggle is violent. But can you wait for people to voluntarily give up privilege while others are dying of exploitation? Gandhi should know. Everything I am saying Gandhi could have said but in some cases he didn’t.

Lee Kuan Yew, the founding father of Singapore, said, ‘I soon realised that before distributing the pie I had first to bake it. So I departed from welfarism because it sapped a people’s self-reliance and their desire to excel and succeed’. He was referring to Nehru’s socialistic approach. How do you see this in a Gandhian context?

Nehru who wanted all of this development – he wanted to create wealth but was also exposed to Fabian socialism. I think many of the things Gandhi said – relevant to the quote – the part of Gandhi that I present and in new ways is an open-ended, dynamic, revolutionary thinker and practitioner. We have to choose: Are you willing to lower your standard of living because people are starving in India and Africa and the US so that we can meet these? If you tell most people in the West or modern Indians in Delhi and Mumbai you should simplify your life because of poor people, it’s hopeless. Gandhi said simple living is high living. People today are consuming so many things. They have so many problems with their health. The more problems you have the better it is for the GDP because then you go to the doctor, the hospital – that’s called good and positive for the economy. Gandhi, to me, would be opposed to that quote. Capitalism produces so much alienation, unhealthy living, stress, and so much violence. To me, unless we change the paradigm to develop as human beings and as societies then we have no future.

Can Gandhi’s philosophy become the governing principle of a nation?

I think in my approach, and it’s in the book, Gandhi did not have all the answers for a nation. For me, in terms of your question, we should be asking ourselves what is valuable from Gandhi and what can we selectively re-appropriate. Some of what Gandhi earlier said about women and their rights is horrible. For instance, he was against birth control. He was against vaccination. Gandhi talks about female purity. But he reformed on most of such issues later in his life. He then understood that those who get raped were victims and it is his responsibility to stand with them. When women were raped during Partition, Gandhi said we should welcome them back and comfort them. Gandhi in the 1940s was much better on so many issues.

If you talk about caste – Gandhi wanted so many changes. But then I talk to Dalits, many follow Ambedkar and many are anti-Gandhi. Ninety per cent of what Ambedkar and Gandhi said about Dalits were similar. But they had differences as well.

When I present my Gandhian approach to Dalits, they say it sounds good but they find people who call themselves Gandhian but don’t help Dalits. Gandhi [as a thought] is necessary for a nation but is not self-sufficient by itself. It also needs many complementary pieces that often had insights that Gandhi didn’t have.

You said Gandhi was not perfect. Yet we call him Mahatma – a title given to him by Rabindranath Tagore. How do you see a man of contradictions being called a Mahatma?

That’s right. In a book I wrote four years ago on Gandhi, I actually researched and indicated that Tagore actually did not coin the term Mahatma for Gandhi but he was the man who promoted it. Tagore is the perfect example to your question. Tagore talks about Gandhi as the Mahatma and at the same time thought Gandhi was imperfect, superstitious and ignorant. Tagore said that some of Gandhi’s superstitions reinforced traditional Hindu superstitions.

I would say it’s a big mistake to call Gandhi as the Mahatma. Because then the people would say he is too good for this world; we will worship the Mahatma. It makes Gandhi irrelevant. He will say I am not the Mahatma, He [God] is the Mahatma. Gandhi is basically telling us to find the Gandhi within us. Usually this reference to the Mahatma is not a way of honouring Gandhi. It is a way of making Gandhi safe.