An entire generation rises against dissemblers, against people who are hypocrites, people whose face and mind reflect different images, and people who are not what they appear or pretend to be. The angst of the youth is against these “phony”, deceptive or insane people howsoever rich or famous they may be.

For avenging them, one takes the law into one’s hands; does wrong things for the right reason or what they think to be the right reason. The violent outburst of angst and revolt against anything phony or fraudulent results, sometimes, in the murder of a famous personality or, in a few other cases, suicide.

Advertisement

Mark David Chapman murdered his idol John Lennon of The Beatles for Lennon’s lifestyle and public statements, especially his much publicised remark of 1966 that the Beatles are “more popular than Jesus.” Chapman found Lennon’s famous lines like “Imagine no possessions;…/ No need for greed or hunger…/ Nothing to kill or die for” totally at variance with the way he amassed wealth and purchased houses worth millions of dollars.

A few months later, US President Ronald Reagan was shot and wounded by John Hnckley, a young man who wanted to impress actress Jodie Foster with whom he had hopelessly developed an obsession. In another case, a sacked employee of a school shot the Headmaster and then held some school students hostage for some hours. He then released them and shot himself.

In all the above cases, which had no apparent link with one another except the sudden and violent spurt of pentup anger and frustration, was one common thread.

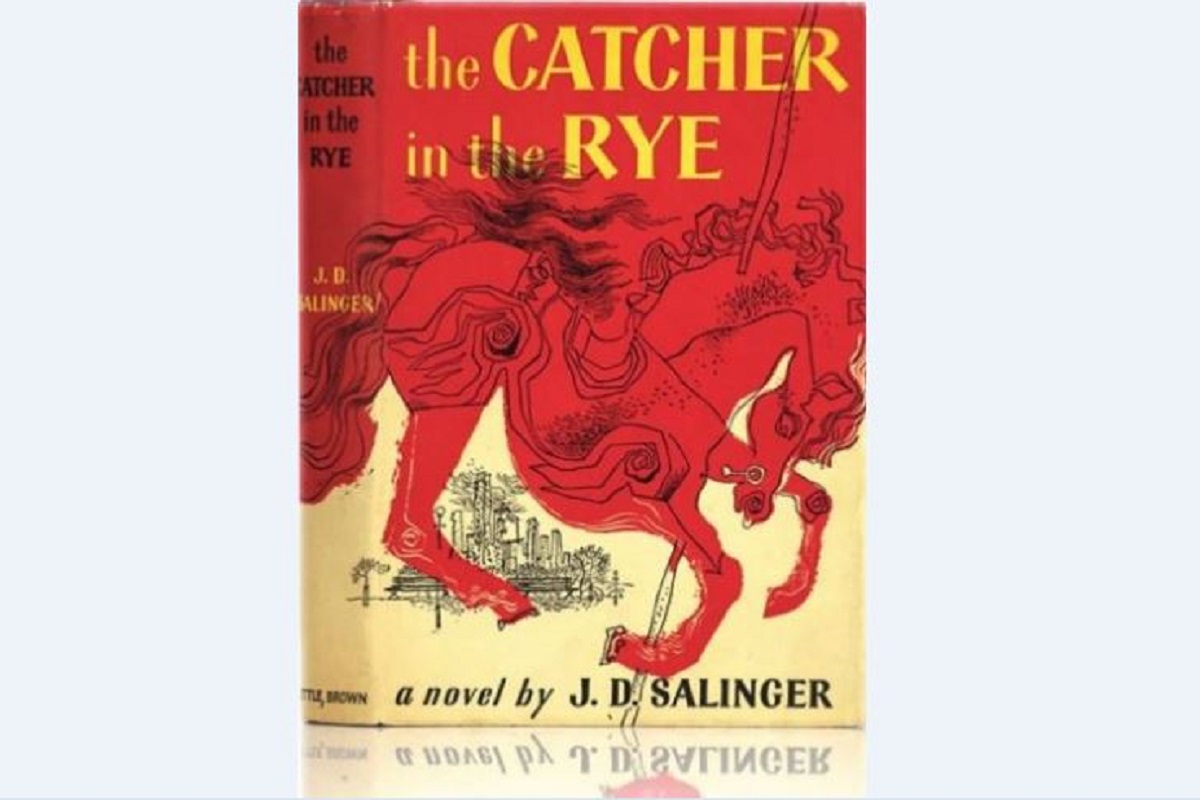

A copy of the same book was found in the possession of the murderer or miscreant in each case. The book was The Catcher in the Rye (1951), one of the most popular post-World War II novels written by JD Salinger (1919-2010) whose birth centenary is being celebrated this year. If the adolescent hallenge to the falsity of an adult society steeped in immorality and artificiality has become a common kind of conformity in American society today, it is the same theme that inspired The Catcher in the Rye.

Salinger burst onto the literary scene after World War II with this controversial novel and his brilliant short stories. The precise and powerful creation of Salinger’s characters, especially Holden Caulfield and the Glass family, has led them becoming a part of American folklore.

Post-World War II critics and students were mesmerised by Salinger’s ironic fiction and his enigmatic personality. At the height of fame he suddenly declared not to publish anything more during his lifetime. Writing was to him a passion and not a mode of earning. He did not want his writing to be corrupted by the pride of commercial success. He endured and was willing to endure any misery, loss or tribulation for the sake of writing and did not join the thriving family business for this passion.

Salinger’s choice of a recluse life, when he became a craze among adolescents

and readers of all ages, completely puzzled critics. After achieving fame and wealth, he withdrew from the public eye and opted for a life of solitude. He gave no interviews and took off his picture from the back cover of his book. He wanted to get rid of phony people and wanted to spend time with children and dolescents who, he thought, had genuine simplicity and pure innocence in their heart. Josef Benson writes, “Salinger represents perhaps the most exclusive and closeted author the world has ever known.

The impetus for his reclusiveness stems in part from his lifelong attachment to very young girls as well as, if to a lesser degree, his reported lack of a testicle. Salinger’s fear of being held accountable for his sexual exploits involving very young girls is a pervasive theme throughout his work and throughout his life.

Like Holden, Salinger never made good on his potential to be a true change agent or transcendent progressive figure. Instead, he opted to shun the world and become more famous for his disavowal of other human beings than for his

desire to be anyone’s catcher in the rye.”

Even after being married Salinger fell in love with a school girl presuming her

to be pure and innocent. Yet he was shocked when he found that she mixed with him only to extract an interview. He also fell madly in love with the beautiful 16-year-old daughter of famous playwright and Nobel laureate, Eugene O’Neill. But while he was away on the Front for military training, she got married to Charlie Chaplin who was at that time 56 and her father’s age.

Escape from deception seemed impossible. Salinger erected a high boundary wall around his house to stay aloof and detached from society as it was presumably full of phony people. Yet Salinger was always in the best-selling authors’ list. His books were published over the course of 12 years, from 1951 to 1963, and his works still remain steadily in print in many languages throughout the world.

Salinger’s reputation derives from his mastery of symbolism, his idiomatic style, and his thoughtful, sympathetic insights into the insecurities that plague both adolescents and adults. Robert Coles reflected general opinion when he lauded Salinger as “an original and gifted writer, a marvellous entertainer, a man free of the slogans and cliches the rest of us fall prey to”.

The Catcher in the Rye, now regarded as a work of adolescent angst, drew such great attention during the 1950s that those years have been called “The Age of Holden Caulfield” in honour of the novel’s sensitive, alienated 16-year-old protagonist.

Holden stands on the fringe of a precipice beside a rye field. Children run playfully through it and Holden keeps alert lest they should come unwittingly to the side of the cliff and fall deep down into the crevice. He wishes to catch them and save their life and in the process play the role of the catcher or preserver of precious innocence and simplicity treasured in children. The book’s vast appeal drew many readers to Salinger’s subsequent short fiction, Nine Stories (1953) and the novella collections Franny and Zooey (1955) and Raise High the Roofbeam, Carpenters, and Seymour:An Introduction (1963). In his novellas, Salinger chronicled the Glass family, a group of seven gifted siblings led by their seer-artist and elder brother, Seymour. Salinger chose not to publish since 1965; nevertheless, as the consistent high sales of his books attest, he has continued to speak, till his death, with warmth and immediacy to succeeding generations of readers.

In many respects, Salinger’s upbringing was similar to that of Holden Caulfield, the Glass children and many of his other characters. Raised in Manhattan, he was the second of two children of a prosperous Jewish importer and Scotch-Irish mother. He was expelled from several private preparatory schools before graduating from Valley Forge Military Academy in 1936. While attending Columbia University writing course, he had his first story published in Story,

an influential periodical founded by his instructor, Whit Burnett. Salinger’s short fiction began to appear in Colliers, the Saturday Evening Post, and most notably, the New Yorker.

Along with such authors as John O’ Hara and John Cheever, Salinger helped sustain the sharp, ironic style that characterises the New Yorker style of fiction.

Among Salinger’s many notable contributions to the magazine, special mention can be made of Esmé – with Love and Squalor, a highly popular story in which a soldier’s ingenuous friendship with a young English girl saves him from a nervous breakdown. Im Crazy and Slight Rebellion off Madison, both of which were published in periodicals during the 1940s, introduce readers to a young man named Holden Caulfield, who would eventually become the narrator of The Catcher in the Rye.

Self-critical, curious, and compassionate, Holden is a moral idealist whose attitude is governed by a dogmatic hatred of hypocrisy. He reveres children for their sincerity and innocence and seeks to protect them from the immorality that he believes contaminates adult society.

Holden’s younger brother, Allie, who died at the age of eleven and is always in Holden’s thoughts, functions as a symbol of unblemished goodness. The Catcher in the Ryeopens in a sanatorium, where Holden is recuperating from a physical and mental breakdown.

Throughout the novel, Holden offers comments on the flaws and merits of American society through which readers may evaluate Holden’s own morals and values. While in New York, Holden struggles between wanting to return to scenes of his youth and venturing into a mature adult lifestyle. In a pivotal scene, Holden decides to lose his virginity to a prostitute, but then comes to sympathise with her plight and changes his mind.

There have been a number of attempts made by Holden to connect with young adults but most of of them go awry. A date with a young woman he considers a “phony” leads him to despise his own conventionality, and a meeting with Carl Luce, an older schoolmate, at a bar becomes embarrassing after Holden gets drunk and asks personal sexual questions. Critics have noted that much of the book’s humour stems from Holden’s misconceptions of adulthood.

After the failed efforts at communication, Holden flees to his younger sister, Phoebe, the only person he completely trusts. Many reviewers and readers of

the book feel that Phoebe Caulfield is one of the most exquisitely created and

engaging children in any novel. A precocious 10-year-old, Phoebe functions as Holden’s salvation. Revealing his obsession with the past and his inability to cope his sister of his wish to be a “catcher in the rye” one who stands on the edge of a cliff near a rye field where thousands of children play.

Holden explains, “What I have to do, I have to catch anybody if they start to go over the cliff….. that’s all I’d do all day.” Phoebe is disgusted at Holden’s unrealistic yet honourable goal. In the novel’s climactic scene, Holden watches as Phoebe rides the Central Park Carousel in the rain, and his illusion of protecting children’s innocence is symbolically shattered.

The richness of spirit in this novel, especially of the vision, the compassion, and the humour of the narrator reveal a psyche far healthier than that of the boy who endured the events of the narrative. Through the telling of his story, Holden has given shape to, and thus achieved control of, his troubled past.

Despite many accolades, The Catcher in the Ryehas also been recurrently banned by public libraries, schools and bookstores due to its profanity, sexual subject matter, and rejection of presumed traditional American values. That said, it continues to lead Salinger’s writings in popularity and it was placed third in a Book Week poll of the 20 best postwar novels. Frank Kermode called it “a book of extraordinary accomplishment”, and George Middleton Murray feels that the book is “a triumph of art”.

While The Cather in the Rye elicited artistic evaluations in the West, in Russia it was judged on moral grounds. Alexander Dymshits praised the book for reflecting “the spiritual bankruptcy of America”.

Not only The Catcher in the Rye, Salinger’s short stories too draw considerable critical attention not all of which, however, is laudatory. In these works, he deals with characters who are neurotic and sensitive people and who search

unsuccessfully for love in a metropolitan setting. They see the egotism and

hypocrisy around them. There is a failure of communication between people

between husbands and wives, between soldiers in wartime, between roommates in schools. A sense of loss, especially the loss of a sibling, recurs frequently.

Many of his stories have wartime settings and involve characters who have served in World War II. In war service, Salinger was engaged in the clearing of a number of concentration camps and there he saw brutality and barbarity of male white supremacist aggression in Nazi activity and found its likeness, later on, rampant in the US. The love for children occurs frequently in his stories for example, the love for Esme, Phoebe, and Sibyl. Like Willam Wordsworth, Salinger appreciates childhood innocence. The message is clear children have wisdom and a spontaneity that is lost in the distractions and temptations of adult life.

A Perfect Day for Bananafish, which introduces the character of Seymour Glass and recounts his suicide, has been read alternately as a satire on bourgeois values, a psychological case study, and a morality tale In Teddy, a story of a boy who is apparently both a genius and a genuine whole man, Salinger gives his most overt expression to Zen Buddhist ideals that inform all of his fiction.

In the short stories of Salinger, the search for spiritual meaning in a superficial world is a thread that unites all the characters. From the pretentious tender-hearted art school instructor in De Daumier Smiths Blue Period to the four-year-old Lionel Tannenbaum experiencing his first dose of adult hatred and bigotry in Down at the Dinghy, the protagonists are disillusioned souls seeking some spiritual purity.

The stories in the volume Franny and Zooey are also remarkable, and they are praised by critics for their structure and characterisation. Franny presents a young heroine who suffers an emotional and spiritual breakdown while attending college. Zooey, the accompanying account of Zooey Glass’s attempt to relieve his sister’s malaise, is praised for its meticulous detail and psychological insight.

The creation of the Glass family cycle is a unique feature of Salinger’s literary

enterprise. Most of Salinger’s later works deal with members of the Glass family, characters who have elements in common with Salinger himself. They are sensitive and introspective, they have phoniness, and they have great verbal skill. They are also interested in mystical religion. “Glass” is an appropriate name for the family.

Glass is a clear substance through which a person can see to acquire further knowledge and enlightenment, yet glass is also extremely fragile and breakable and therefore could apply to the nervous breakdowns or near breakdowns of members of the family. The Glass family also attempts to reach enlightenment through methods of Zen Buddhism. The basic idea of Zen is to

come in touch with the inner workings of our beings, and what Seymour, Zooey and Franny Glass want to do is to come in touch with the inner workings of their being in order to achieve non-intellectual enlightenment.

Many critics condemn the Glass family as self-centred, smug and perfect beyond belief, but few deny the immediacy and charm of the Glass clan who are so successfully drawn that numerous people over the years have reportedly claimed to have met the brother-in-law of a Glass.

Salinger’s works have been considered both profound and immature, the inheritor of Kierkegaardian idealism as well as the most distrustful of ideas. His brand of activism has interiority with no clear political agenda but many reviewers consider his characters to be serious critics of their world. What he celebrates is the spontaneous, passionate and accidental.

Salinger, writes Donald Barr, is “preoccupied with the collapses of nerve, with the cracking laugh of the outraged, with terrifying feelings of loneliness and

alienation”. He seems to correspond peculiarly to the psychological aura of our moment of history and he has expressed some of the values and aspirations of certain young people in a way that nobody since F Scott Fitzgerald has done.