State of media in focus at 10th Editors’ Conclave

Speakers lament threats to media, stress on need for independent journalism.

(PHOTO: SNS)

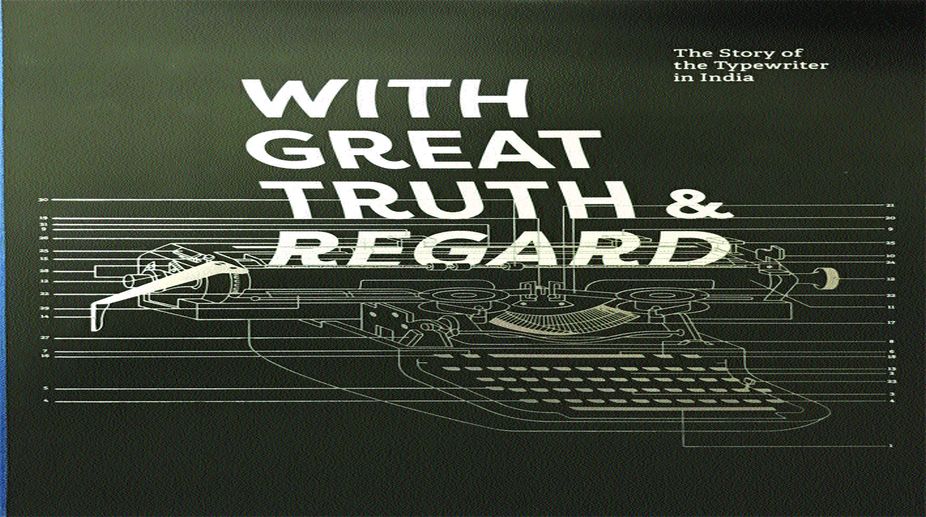

A unique presentation by Sidharth Bhatia, With Great Truth & Regard is a creatively compiled assimilation of facts about the first Indian typewriter manufactured by Godrej and its history down the decades: first as it grew in stature and importance in every office and its impact on the corporate world; then its ultimate decline with the advent of computers that were so completely versatile in every “task” that they completely obliterated the need for typists altogether.

The Foreword by Jamshyd N Godrej sets the mood of this journey down memory lane. He pays tribute to his father, Naval Godrej, primarily responsible for manufacturing the first Indian manual typewriter; the American Remington was the other company whose typewriter machines were imported into India.

Despite being a decidedly heavy book, (quite a deterrent for today’s Gen Y who prefer to skip reading anything that’s in fine print, let alone carrying something that unwieldy), if the reader merely took a peek into the pages, they would involuntarily be drawn into this fascinating “window to a lost world”.

Creative planning and assiduous monitoring of diverse information make the browsing turn into a thoroughly delightful read, and if one is somewhat senior in years and has experienced life in the seventies, eighties and even nineties when this “literary piano” ruled the roost in every office, private or government, one would surely relate to the central thought that surfaces in the pages, “The King is dead, long live the King”.

It’s a cry of nostalgia for the past that can never be brought back to the present. Bhatia asks, “The age of the typewriter is nearly over… (it) has a history, but does it have an Indian history?” And thus an illuminating journey into the past begins. Bhatia very insightfully notes the important role a typewriter played along the passing of the decades, especially inadvertently leading to women empowerment by virtue of their being employed as typists and secretaries.

Another very valid point Bhatia makes is that even in today’s world of instant correspondence via emails, rather due to the fear of vital information getting leaked through hacking, a “confidential letter” is typed by hand to ensure its privacy. And this goes as much for the highest office in government to the closed door of the CEO in a private company.

Getting back to the moot point of typewriters being instrumental in helping women find self-esteem through employment, the movement began in the 19th Century itself. A widely accepted fact in the USA and Britain is that the typewriter revolutionised female employment. Bhatia elaborates, “In the US in 1870, women formed only four percent of the 154 typists and stenos which rose to 96 per cent by 1930”.

Quaint pictures, illustrations and photographs from publications down the decades add striking facets to the text. In fact, some pages deliberately printed in the old world quinte-ssential “typewriter font” highlight the appeal even further.

Generous doses of humour through anecdotes by illustrious persons and their personal bonding with this once-ubiquitous machine fill many of the pages of the beautifully crafted tome. There are inputs by those who still use the typewriter despite the proliferation of laptops and tablets.

Eminent, well-loved author Ruskin Bond prefers to type rather than write long hand and most of his novels and short stories have been hammered out on his 50-year-old Olympia. Sitting in his sun-dappled room living room at Landour, Bond has recalled, “I have written about 80 novellas, 200 short stories and countless articles” (on the typewriter).

Bhatia extols the emotional connection between renowned authors with their typewriters. Ernest Hemingway had his Royal portable ready in his bedroom in case an idea struck him, while George Orwell called his Remington as his “right hand man”; and that Agatha Christie could write anywhere, all she needed was “a sturdy table and a typewriter.” In India, RK Narayan, Dom Moraes and Busybee all had their own “machines that they pounded on and produced eminently readable works.”

Behram Contractor, better known as Busybee, writes in this book, “People sometimes ask me how I write… I roll the paper in the Underwood, set the margin, and sit back. The Underwood then writes the column”.

Bachi Karkaria, in the section “The Keys to Our Kingdom” writes, “Typewriters were part of the world’s corporate consciousness. By being chained to its red and black ribbon, a million women were liberated”. She mentions the nostalgia of Calcutta of the sixties, of working at The Statesman as an assistant editor and recounts some humorous anecdotes reflecting male chauvinism dominating that particular era.

“The Shift from Typewriters to Computers in Journalism” by Naresh Fernandes is a glance into office of The Times of India with its allied incidents of the 1990s.

Nuggets of peculiar information with related pictures or illustrations form an integral part of this tome. For instance, it is mentioned how Vasudeo Barve’s claim to teach typewriting in 25 minutes won him an entry into the 1992 Limca Book of Records and since 1988, the 84-year-old has been teaching students and professionals how to type in 25 minutes without looking down at the keys!

“The World of Steno Stereotypes” explores the mindset of Indians who tend to associate stenos and typists with women. However, Bhatia adds, “Despite the sexual stereotypes, Christopher Latham Sholes, the inventor of the first typewriter, was shown in a 1930s book as a savior of women”.

The tongue-in-cheek humour includes a Mario cartoon that refers to the “Menace of ‘lady typewriters’ in the office” and emphasises the important role she played because of her close access to the boss and how she had to be kept in good humour by colleagues.

However, underlining the main thought all along is the deep regard for his employer and the company Bhatia has been associated with for many years — Godrej. Nonetheless, the remarkable volume is a labour of love and after reading it, if you have an old typewriter packed away somewhere, you will be tempted (like I was with my portable Remington) to pull it out, dust it lovingly and type out a few pages. The strangely comfor-ting sound of the clacking keys is certain to transport you back to a beautiful “lost” era.

(The writer is assistant editor, features, The Statesman, Kolkata)

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement