Equus & other stories: M. Narayan’s masterful blend of motion, culture, and emotion at Bikaner House

M. Narayan’s Equus & Other Stories, curated by Uma Nair, brings a striking blend of movement, tradition, and storytelling.

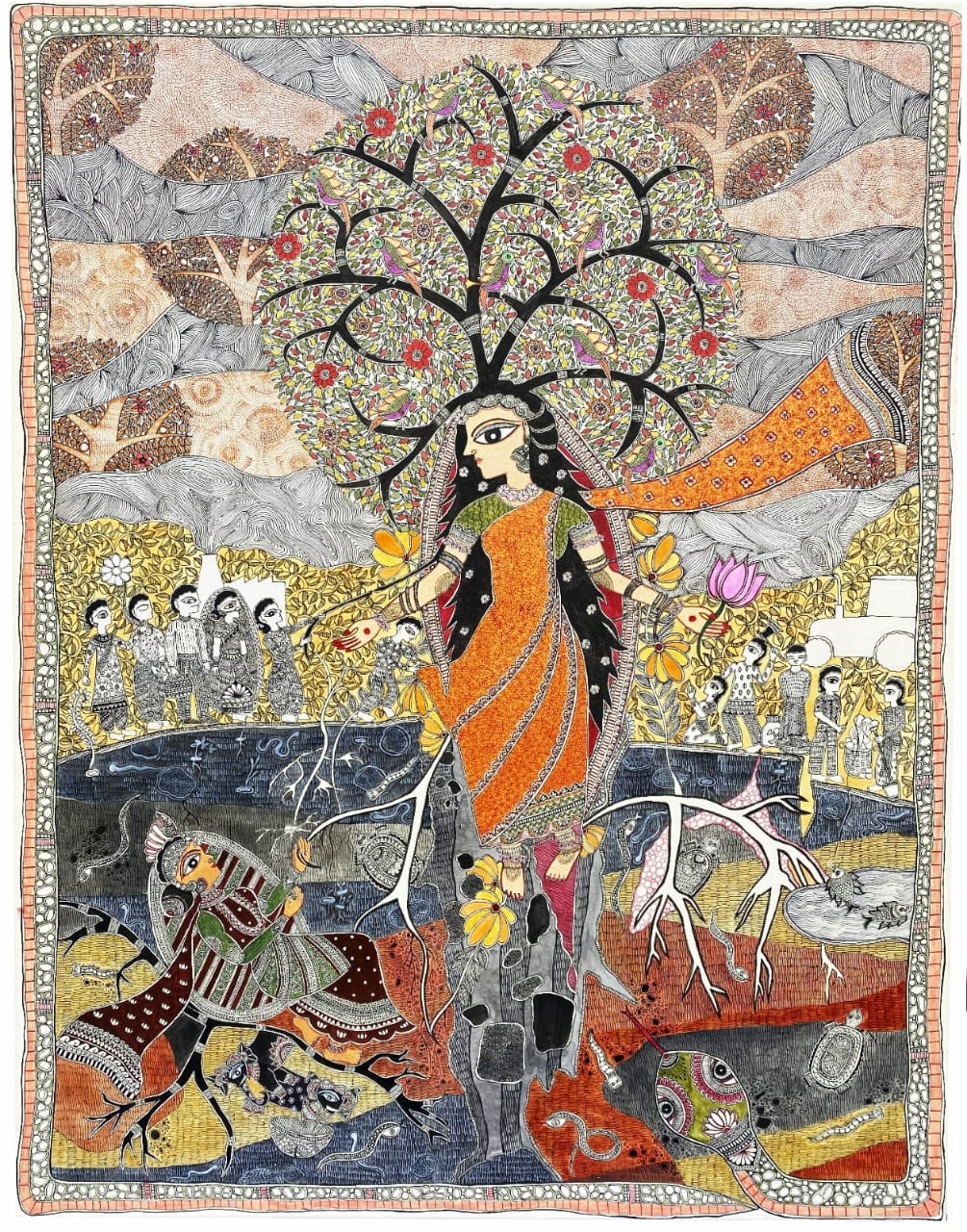

An exhibition titled “Vaidehi-Sita Beyond the Body” provided a platform to present and discuss alternative interpretations of traditional narratives, especially in traditional painting styles amongst artists, scholars and writers alike. The Sita in the paintings at the exhibition is far removed from the quintessential depictions of a dutiful wife and mother, but a woman who made choices, acted willfully and lived by her principles.

Vaidehi-Sita Beyond the Body-SNS

The Ramayana in India is sacred, profound and omnipresent. In the words of Tagore, “These two epics (Ramayana and Mahabharata) embody what India cherishes as its ideals.” Its affinity with people is such that many recensions and versions of this sacred text exist.

The protagonists in this sanctified epic and its multitude of regional variations are associated with ideals and virtues desirable in the times. It is interesting to note that even though sacred, the Ramayana, Ram and Sita have seen subjective interpretation in art, writing and songs and all the more so and sometimes in very controversial forms in the dynamic India of now. Traditional narratives like the Ramayana are also fundamental subjects in folk art styles. With the times, these painting styles are also evolving to include illustrations of personal understanding of the sacred epics and characters.

Advertisement

Advertisement

One exhibition titled “Vaidehi-Sita Beyond the Body” provided a platform to present and discuss alternative interpretations of traditional narratives, especially in traditional painting styles amongst artists, scholars and writers alike. It helped with food for thought on the protagonist Sita in the Ramayana, Mithila, the contemporary take on traditional Indian mythology in Maithali art and the importance of innovation and evolution in traditional art forms.

Hosted at the National Crafts Museum and Hastkala Academy, New Delhi, the production was the result of the efforts of the Center for Studies of Tradition and Systems, JNU, Delhi, in collaboration with IGNCA Delhi, National Crafts Museum & Hastkala Academy, New Delhi and the Ministry of textiles.

To mark the occasion of the Amrit Mahotsav, India’s 75 years of Independence, the exhibition Vaidehi presented a collection of over 75 paintings in Mithila painting style, popularly known as Madhubani painting on Vaidehi or Sita, from the Hindu mythology of Ramayana.

For the unversed, the Mithila painting is from Bihar’s culturally vibrant Mithila region. This folk painting style is a holistic tradition of visuals, accompanied by rituals and songs. It is also one of the few Indian crafts that have been widely valued and acquired as an artistic style beyond the practicing members of the Mithila community. Also, Sita and Mithila are synonymous. Mithila in Ramayana is the birthplace of Sita. The people of Mithila believe themselves to be her extended family. The Folk songs and sayings refer to and worship Sita as the daughter of Mithila or Janaki, the daughter of king Janak. Hence, the exhibition was a compelling combination of subject and art technique.

With the combination of the traditional folk style of Mithila painting and the religious subject of Sita, one may feel the Vaidehi exhibition full of heavy-weight traditional depictions; on the contrary, the distinctive and potent representations of Sita were a unique feature of the works. A subject as sacred as the Ramayana and the pious Sita were open to critical inquiry, subjective understanding and interpretation in these paintings.

The protagonists in sanctified epics, like the Ramayana, are associated with ideals and virtues desirable to the times. The Sita in the paintings is far removed from the quintessential depictions of a dutiful wife and mother, but a woman who made choices, acted willfully and lived by her principles. The depiction of Sita as a successful single mother, a courageous woman who stood up against the mighty Ravana, or as a self-reliant person living in the forest are values that we find in her and associate with today. These values differ from a generation ago when grandmothers narrated sympathy for Sita’s plight and only glorified her as a loyal wife. Such notable changes in narration and depiction, especially within folk painting styles, mark a remarkable shift in the desired values within our society and in how the Mithila folk art is evolving to include subject matter beyond ritualistic drawings.

Some works also explore depictions of Sita in regional versions of the epic. The most moving one to me was Sita slaying a thousand-headed Ravana (Saharsha-Mukha Ravana) by Amirta Ravikumaran. It is based on Adbhuta Ramayana, a variation of the Valmiki Ramayana. The Adbhuta Ramayana is believed to be the eighth Kanda or supplement to the Valmiki Ramayana; it has three parts. The third part describes the killing of Saharsha-Mukha Ravana by Sita in the form of Devi.

Even though a depiction of traditional narratives, it brings to light a different portrayal, a powerful one in comparison to the Sita in Valmiki Ramayana, The exhibition presented works from artists of diverse origins and identities. There were paintings from the Mithila region from artists belonging to the community which practices the art form traditionally to artists who have adopted the style of Mithila painting for their art, based nationally and internationally.

The representation of the subject varies from traditional to very contemporary. The works are done in acrylics on canvas, unlike the conventional natural colours and ink. Also, a sizeable number of the exhibits present unique interpretations of the traditional line-work and compositions atypical to the Mithila style, showing almost POP art-like design qualities.

Here the paintings make one reflect if such explorative works deviating from the traditional motifs, colours and compositions mean we are losing out on the traditional practice and technique or if it showcases the much-needed evolution of the traditional artistic style as culture evolves. But as tradition is not static, such change and innovation, in the end, seem essential and natural for a traditional style to sustain and find relevance in time. After all, Mithila art is as much about the present as ritualistic depictions. Besides, one may ask why specimens of art from the past are believed to be more authentic than their current form. Is it something to do with our biased belief that anything from the past is essentially truer? Or is it because we ignore that culture is alive and evolving, and so are traditional craft and artistic styles that are a tangible reflection of this evolving culture?

The exhibition Vaidehi, Sita Beyond the Body, was fascinating from the viewpoints of artistic practice, culture, mythology and a wholesome reflection of the evolving understanding of our traditional narratives that are an indispensable part of our heritage. I believe similar endeavours will help create awareness and generate dialogue around our folk painting styles and help break the glass ceiling between fine arts and folk and the tribal styles of expression.

Advertisement