Parents and children in east of India still willing to buy and read books: Survey

Children’s books are selling like hot cakes at the International Kolkata Book Fair at Boimela Prangan in Salt Lake.

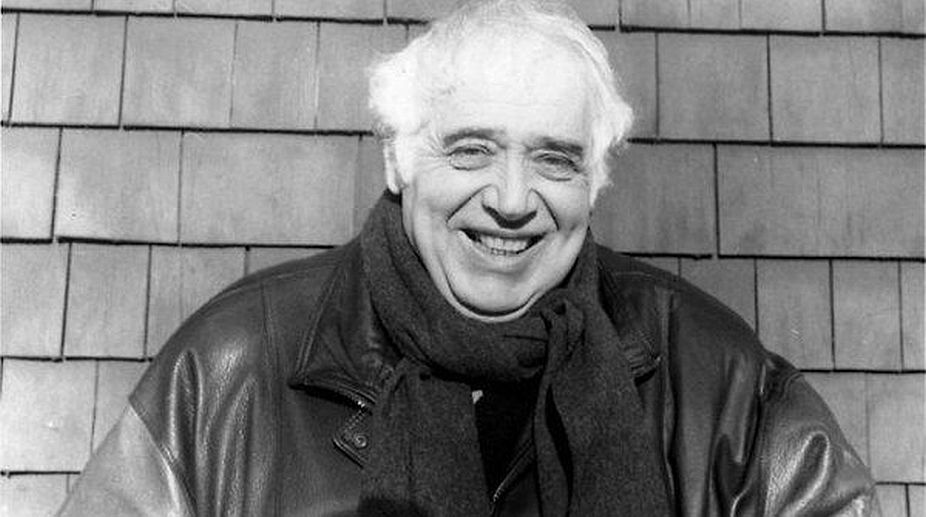

Harold Bloom (PHOTO: TWITTER)

If I have understood Harold Bloom correctly, then I have misunderstood him. If I have got him right then I have got him wrong. Such is the law of misprision. I am bound to misinterpret everything he says. Again, if I have got the gist of his argument, I may have to kill him, or at least wrestle with him, overthrow, usurp, or subsume him. In an Oedipal way, of course!

At the age of 86, probably the greatest living literary critic on the planet, the Dr Johnson de nos jours, nothing worries him too much. Except maybe death and oblivion! But even then I think he has worked out a way around it —a modest, secular form of resurrection.

Advertisement

For a few decades, I had only read Harold Bloom. Such landmark works as The Anxiety of Influence (the agonistic struggle of poets with their major influences, like Wordsworth versus Milton, Plato versus Homer) and The Book of J (his hypothesis that certain chunks of Genesis and Exodus were written 3,000 years ago by a woman, perhaps a princess and daughter of Solomon, and woven into the Pentateuch). And then, on a vaster scale, The Shadow of a Great Rock, his literary appreciation of the entire Bible, and Shakespeare: the Invention of the Human. But then, a few months ago, I got the summons from the great man himself. Which sort of blew me away. Just a little bit like, in my own realm, hearing the voice of God finally, after just reading the Commandments.

Advertisement

He had read an article of mine and wrote to me that it was “a valiant attempt” and I should come and see him some time. So I bounded over to his house in New Haven, an hour and a half out of New York on the train, home to Yale University where he has taught for his entire life and is the Sterling Professor of Humanities. “You’re a young rascal,” he told me. A phrase you’re not going to hear too often. “You look about thirty-something.” Obviously his eyesight is not everything it used to be. “I feel we have known one another for years and you are already an old friend.” I pretty much fell in love with him. That’s how it is with the ephebe and the precursor. You have to fall in love even though you are doomed to, first, misconstrue, and then, finally, “turn away from” or rebel against him.

I was rebelling against him straight off the bat, to be honest. “Man, are you crazy?” I said. He had a doctor attending to him while I was there. Something to do with his legs. And yet, that very afternoon, he was teaching yet another class. He teaches over Skype now. His students used to come and see him and then the Yale bureaucracy outlawed that on account of some kind of anxiety of insurance. What if a student tripped and sprained an ankle? Obviously, from a Yale point of view, I was living dangerously just hanging out with him. I said, “I’m always telling my students, ‘Don’t be a hero!’” But Harold is a hero. A hero of the humanities. No way is this guy going to stop teaching. Ever. He wants to die with his boots on. “Come back soon,” he said on parting.

So naturally I had to go back, but only after I’d read his new book, Falstaff: Give Me Life. It’s the first in a series of “Shakespeare’s Personalities”, with Hamlet, Iago, and Cleopatra also in the pipeline. You read Bloom in part for the asides, like the time WH Auden stays over at his place and they lock antlers about Romantic poets, but find agreement over Falstaff, “I recall his saying that he preferred Verdi’s Falstaff to Shakespeare’s yet thought Sir John was closer to redemption than all but a few other people in the plays. I replied that Falstaff courted and accepted the obliteration of rejection.”

In one of his books, he wrote, “Bloom is only a parody of Falstaff.” He used to look a lot like I imagined Falstaff, only he’s lost a bit of weight recently. The Fat Knight, but on a strict diet! He has this theory that people tend ultimately to be either more Hamlet, “an abyss, a chaos of virtual nothingness”, a quintessence of dust, or Falstaff, overflowing with vitality and perpetual laughter, for whom “the self is everything”. I’m more Hamlet, he is definitely more Falstaff. Which is basically why he has written the book. It’s his homage to a character he feels he knows well. Or who, to put it in a Bloomian way, knows him. This is one of his great theories — that Shakespeare, with his vast vocabulary of 22,000 words, “an art so infinite it contains us”, knew pretty much everything there is to know about humankind. That he therefore “invented the human”.

Which of course sounds absurd, at first glance. Nobody invented the human, if not Yahweh. If we allow that humanoid creatures first starting prowling about some seen million years ago, then the only thing that invented the human is time. Aeons of time, combined with the series of mistakes in transmission that we call evolution. Another form of misprision, where the next generation is a screwed-up version of the old one, genetically speaking, but also, perhaps, a form of progress, in terms of adaptation to the environment. But no, says Bloom, Shakespeare invented the human.

He once wrote, “those Americans who believe they worship God actually worship three major literary figures, the Yahweh of J, the Jesus of the Gospel of Mark, and Allah of the Koran.” For Bloom, Shakespeare is scripture. He semi-seriously wonders if there could be a secular religion of Hamlet, for example. The whole point of “imaginative literature”, he argues, is the creation of vehement personalities, diverse characters, “distincts”. The phrase he uses about Shakespeare’s characters is that they are all “artists of themselves”, they appear self-created, fully autonomous. But here is the thing, and this is the only way to make sense of his inventing-the-human, they have (in part) created us, now. All those great Shakespearean figures have so hugely impacted on our consciousness of what it means to be human, that they have affected our concept of ourselves, and therefore shaped us, in another millennium, since we are what we think we are, up to a point. There is a lot of Shakespeare in Freud, for example. After Shakespeare, we are all Shakespearean, whether we like it or not, all doomed to strut and fret our hour upon the stage.

Part of what keeps him going and stops him from putting his feet up is his agon against the Shakespeare-haters. He feels that the Academy, at least in the humanities, has been going in the wrong direction for the last half-century. We have what he calls the “French” Shakespeare, in which great works are reduced to epiphenomena of language or politics or economics, a Marxist or Freudian or feminist Shakespeare, a deconstructed or Foucault-up Shakespeare, diminishing and impoverishing. Reduced Shakespeare is now, he believes, the norm, governed by the “fear of the Dead White European Male”.

Towards the end of The Shadow of a Great Rock, in analysing the Book of Revelation, he writes that “When I was a young literary scholar, I remember being fascinated by the genre of apocalypse. I turned 80 just two days ago and find I now have a certain distaste for apocalyptic literature.” A few years later, he is still capable of sounding a certain apocalyptic note. “After a lifetime spent in one of our major universities, I have very little confidence that literary education will survive its current malaise.” But the campus only reflects a wider society, “The universe increasingly has a common technology and in time may constitute one vast computer, but that will not quite be a culture.”

He is not above the magisterial putdown. He does not rate the original demotic Greek of the New Testament very highly. When I mentioned the work of a rival Shakespeare scholar, he shot back, “It is not a good book.” Of a friend of mine (let us call him “Fred”), he said, “I have read his work on Wallace Stevens and his work on Freud. I could find nothing in them of either Wallace Stevens or Freud. Only Fred.” Or how about this on Norman Mailer —“he has written no indisputable book… He is the author of ‘Norman Mailer’.” It’s all part of what he calls “antithetical criticism”.

Bloom has become a brand and a “study guide”. You can find Blooms Major Dramatists, Blooms Major Poets, Blooms Major Short Story Writers, and so on. It’s a bit of an industry, almost an empire, and there must be something of the agon in all this surely, a vaulting ambition or desire for dominion. But Bloom hates more than anything “the death of the author” school of thought. He wants to bring authors back to life.

I happened to mention Bertrand Russell’s doubt about the definite article, where authors were concerned. Russell reckoned that you couldn’t say that Sir Walter Scott was “the” author of Ivanhoe, because “you would have to survey the universe and demonstrate that everyone in it either did not write Ivanhoe or was Scott”. Bloom dismissed philosophical doubt with a wave of the hand. Scott is the author. So too is Bloom. Bloom is the Bloom, radically distinct, the artist of himself. Bloom is what he would describe as a “strong reader”, but he is also a “strong writer”, with a sense of purpose and conviction and passion, standing erect on the lectern of his own sublime subjectivity. “I too am what I am,” he wrote at the end of the The Shadow of a Great Rock, consciously echoing Yahweh in Genesis.

“Come back on Easter Monday,” Harold said to me, as I was leaving. “I feel an intense friendship towards you.” Of course, Harold, I’ll come back. He has this velvety bass voice, tinged with pain.

If Bloom himself were writing this, I am sure he would call to mind some reference to James Joyce and Leopold Bloom, hero of Ulysses. But the phrase that springs to my mind is a passing remark from an old barber of mine, no longer with us. “The bloom has gone,” he said one day, out of the blue, inspecting my hair closely for signs of decadence. A worrying thought. But I think I could now say in response, “You’re wrong, Albert. The Bloom has not gone. The Bloom lives. The Bloom blooms.”

The writer’s latest book is Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me. He teaches at the University of Cambridge

The independent

Advertisement