Play review | The Enemy: Say no to war

Pearl S Bucks short story set in World War II came alive on stage in the Capital

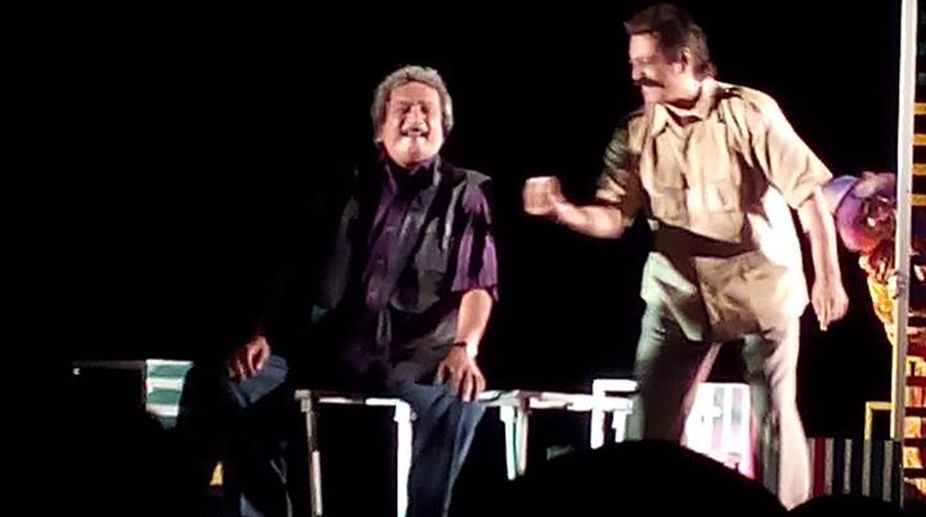

Premkatha (Photo: Facebook)

The immortality of any piece of writing, especially one that is targeted at proscenium performances, lies entirely on the universality of the narrative plot.

Therefore, though Moliere’s The Miser—adapted, contemporised and performed in Bengali —was first staged almost four centuries ago in September 1668 in Paris, it remains as contemporary as it was when first produced.

Advertisement

Comedy and satire, if written intelligently by weaving into it a critique of the social system, can work wonders on an audience even 400 years later.

Advertisement

That is perhaps what made Sayak and its founder-director Meghnad Bhattacharya choose The Miser to be presented as Premkatha (Sagas of love). The original French play is said to have been loosely based on the Latin comedy, Aulularia by Plautus, from which many incidents and scraps of dialogue are borrowed, as well as from contemporary Italian farces.

Sayak’s performance stands as a testimony to the theme’s immortality. The Bengali adaptation looks as fresh, topical and contemporary as if it was written today. Chandan Sen has placed it in contemporary Kolkata, which imbues the play with the correct regional flavour for the audience to get the hang of it without referring to Moliere’s original.

Prankeshto (Meghnad Bhattacharya), a widower in his late sixties, runs a successful business as a cloth trader in Kolkata. He has two adult children, a daughter Pulokita (Antara Dey) and a son Palash (Ajoysankar Banerjee) who call their father Chippu because he is a merciless and pathological miser.

He is willing to marry his daughter off to a widower twice her age on the sole ground that the aged bridegroom has agreed to marry her without a dowry.

He announces that he will marry a poor young girl, Prerona (Anamika Bhattacharjee), who manages to eke out a living for herself and her widowed mother by supplying fried puffed rice to different shops. He organises a “bridegroom watching” ceremony in his own house, warning his chef-cum-driver not to fill the car with more than one-and-a-half litres of petrol to bring the bride’s party home.

But there are problems.

Pulakita is in love with Dolgobindo (Samiran Bhattacharyya) who works in Prankeshto’s shop. Palash is in love with Prenona and is trying to raise a loan from the market to set up his own sweet shop to be free from the miserly clutches of his father.

While trying to raise the loan through a corrupt loan agent, he finds that the way to getting the loan is fraught with so many obstacles that he would perhaps be better off without it! But then, how would he marry Prerona who he dreams of “rescuing” from her dire straits?

Both Palash and Pulakita, despite the education their miserly father has provided, are worthless in the world, unable to make anything concrete of their lives except talking tall and criticising their father. The family retinue Phajil (Uttam Dey) is thrown out of his job by Prankeshto because the latter suspects him of trying to steal the gold he hides in the house.

His suspicions are correct. His cook and driver are one and the same, disgusted with the way his boss treats him. The marriage agent Jhorapata Patronobis (Indrajita Chakraborty) who wears Westernised clothes and labours over her English accent is actually targeting Prankeshto as a prospective groom for Prerona because she wants him to fund the NGO she works for!

Every single character is on a self-seeking, axe-grinding expedition and basically, not that different from the protagonist, Prankeshto.

Sociologically speaking, the play is an incisive critique on the selfishness of ordinary people on one hand and of the self-aggrandisement of people like Prankeshto on the other. Premkatha, the title, can be taken seriously if one takes the happily-ever-after ending as the closure.

But if probed deeply, the same title, from a different perspective, can be read as a satiric title in a play where love plays an ironical role. The names of characters are a wonderful strategy for invoking laughter among the audience. Jharapata is a human personification of “shed leaves” with a thin form, while Phazil, which means “one who always cracks jokes”, turns out to be a joke unto himself.

The director has used a chorus, which is dressed up as jokers in a circus to emphasise the satire. The chorus moves in and out of the proscenium space to sometimes move silently or echo responses of the characters and move the props to execute a change of scene. They look quite colourful but tend to drag after a point of time.

There are no “serious” scenes in the play. The acting is outstanding with special commendations for Meghnad Bhattacharya, Ajoysankar Banerjee and Indrajita Chakraborty.

But sometimes, the actors tend to go over the top. Meghnad blinks all too often during his spaces.

It is much more difficult to perform a satire-cum-comedy than it is to stage a tragedy or a whodunit and the actors have done justice to their natural way of approaching the characters that they have fleshed out.

What has led to many language and culturally different versions being staged down the years is that Molière’s humour does not translate well and requires more or less free adaptations to succeed.

Premkatha, celebrating the 44th year of Sayak in Bengali theatre bears that out and some more.

Advertisement