Parents and children in east of India still willing to buy and read books: Survey

Children’s books are selling like hot cakes at the International Kolkata Book Fair at Boimela Prangan in Salt Lake.

Between 2006 and 2019, Chatterjee featured in five films helmed by Ghosh ‘Podokkhep’ (2006), ‘Dwando’ (2009), ‘Nobel Chor’ (2012, guest appearance), ‘Peace Haven’ (2015) and ‘Basu Poribar’ (2019) and as much a perceptive account of the dynamics of an actor-director association, the book is a story of the friendship between two creative individuals.

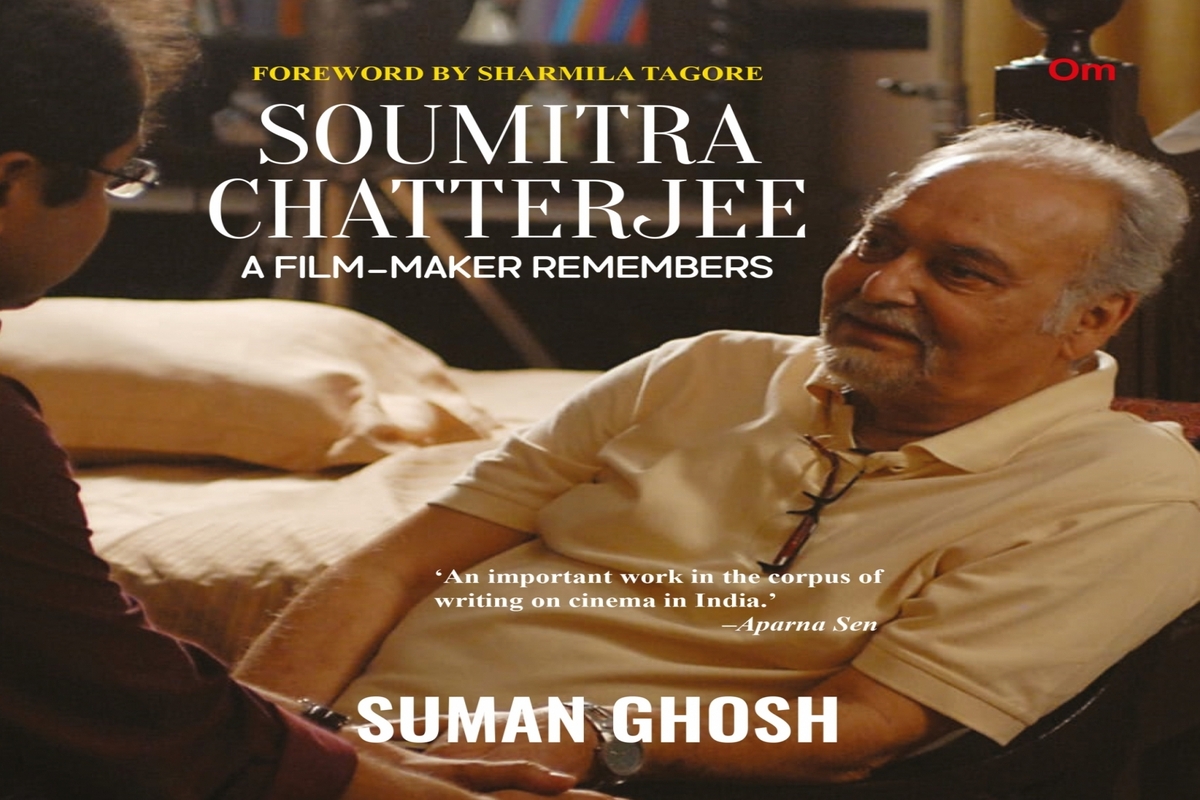

'Soumitra Chatterjee never considered himself bigger than the director's vision'. (photo: IANSLIFE)

Humility, a lust for life, a quest for perfection, all this and more comes across in a heart-warming tribute to Soumitra Chatterjee, who mesmerised the cinematic world for more than 60 years with a staggering oeuvre of over 250 films, 14 of them with Satyajit Ray – won a National Award for Best Actor in 2006 and who continued to appear before the camera almost to the very end till he passed away aged 85 on November 15, 2020.

“He was by far the most vibrant person I have met. His lust for life knew no bounds. Whether through literature, through poetry, through films, through his interactions with people, through theatre, it was as if he wanted to perpetually soak in the delirium of life and be bathed in all its beauty. His mind was like a blank canvas, ready to be painted with colours”, Suman Ghosh, a professor of economics at Florida Atlantic University and trained in the film genre at Cornell, writes in “Soumitra Chatterjee – A Film-Maker Remembers” (Om Books International).

Advertisement

“Basically, he never considered himself bigger than the film, or the director’s vision. He submitted himself completely to the director’s vision and conveyed that vision without distorting or damaging it. When it comes to the relationship between a director and an actor in the making of a film, it’s like walking together, searching together and becoming one,” writes Ghosh, whose debut directorial ‘Podokkhep’ won Chatterjee his National Award.

Advertisement

“Hence, what Soumitra-kaku always tried was to understand the director (both as an artist and as a person), his or her vision, and then travel together, wired to the director’s vision, in step with that. He then had to just ‘do’ or ‘be’,” adds Ghosh, who, over their association for more than 15 years, came to regard Chatterjee as a father figure, hence the “kaku” appellation.

The bond was mutual.

“My parents are not star-struck people (but) one day my mother asked me whether it would be possible to request (him) to come to our house (for lunch),” Ghosh writes.

Chatterjee enthusiastically accepted the invitation. “Soumitra-kaku really enjoyed the meal and I was so happy to see the joy on my mother’s face. Before leaving he thanked my parents for a wonderful afternoon. While returning home with me in the car it was interesting that he remarked, ‘Tomader puro paribar ke ki apon laglo. Ekta odbhut sohoj shorol byapar achhey’. (I felt so close to your family. There is a simplicity about them which is so endearing),” Ghosh writes.

Truly, this is the mark of humility of an actor rooted firmly on the ground. It was Chatterjee’s humility that once prompted him to “give way” to his co-actor Mithun Chakraborty, way his junior in the profession, during the filming of Ghosh’s “Nobel Chor” when he found the latter unable to maintain the dialect of the village in which the film was being shot and which the thespian had mastered.

There are examples galore of Chatterjee’s quest for perfection. For instance, ‘Podokkhep’ concludes with Chatterjee quoting from the Mahabharata: ‘Na narmayuktam vachanam hinasti na strishu raajan na vivaahakaale/Praanaatyayee sarvadhanaapahaare panchaanrutaanyaahurapaatakaani’ which basically lists the five situations in which telling a lie is not sinful.

Chatterjee actually telephoned Nrishinga Prasad Bhaduri, an Indologist and authority on the epics, to understand the meaning and ensure he had the pronunciation right, Ghosh writes.

Chatterjee was “such a pleasure to have around the sets” and his innumerable stories from yesteryears and anecdotes from experiences as an actor were a treasure trove”, the author writes.

“Over my interactions with him for fifteen more years I found out that he possessed a fund of never ending stories. For example, during the shooting of ‘Abhijan’, Robi Ghosh and he were casually chatting with each other and Kaku was narrating an incident which involved using the choicest cuss words. At one point, Robi Ghosh realised that Satyajit Ray had come up and was standing behind Kaku. Kaku did not realise this and continued in full flow.

“Suddenly, he saw Robi Ghosh making strange facial expressions, trying to alert him. Kaku turned around , utterly embarrassed that Ray had been privy to everything he had said. Making light of Kaku’s mortification, Ray remarked, ‘Shono, ja bolbe censor bachiye bolo’. (Listen, whatever you say, keep in mind the censors.) They all burst out laughing,” Ghosh writes.

And there are some extremely poignant moments, for instance, when Chatterjee, in the nick of time, found his Sorbitrate tablets when he sensed a heart attack coming on.

“Ever since, I kept pondering about the many discussions Soumitra-kaku and I had about ‘death’. He used to tell me often that he could now see ‘death’ approaching. This was primarily after he was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2010. His only wish was that it should come quickly, whenever it had to. He shuddered to think of himself as a burden to his family, suffering a slow and agonising end.

“We would also stalk about ‘death’ in literature and how authors have written about this phenomena – from Tagore to Tolstoy to Simone De Beauvoir. I always felt that Soumitra-kaku was quite cavalier about death. It was the ultimate truth and one should accept it that was his viewpoint. It is interesting that later, in my film ‘Peace Haven’, I explored ‘death’ head-on, with Soumitra-kaku performing one of his most poignant acts on facing death,” Ghosh writes.

In fact, there was even a bizarre idea around a film on death that both wanted to work on – that Chatterjee termed “a brilliant idea” – but which never materialised.

Between 2006 and 2019, Chatterjee featured in five films helmed by Ghosh ‘Podokkhep’ (2006), ‘Dwando’ (2009), ‘Nobel Chor’ (2012, guest appearance), ‘Peace Haven’ (2015) and ‘Basu Poribar’ (2019) and as much a perceptive account of the dynamics of an actor-director association, the book is a story of the friendship between two creative individuals.

“I still cannot forget his smile, his laughter, his jokes, the knowledge he imparted, but mainly his presence. It was as if he would be there, always…like the age-old banyan tree.

“Writing this book was a cathartic experience for me. Yes, it was painful to relive the memories. But who said that all pain is bad? Writing this helped me emerge from the deep sorrow that has engulfed me after his demise. This is not an analysis of Soumitra Chatterjee’s life and work. So I do not even attempt to be objective in my writing. Can one truly be objective about one’s father? Rather, I have tried to share anecdotes about him as a person and as an actor which can only provide a glimpse of the person he was,” Ghosh maintains.

Advertisement