‘Ramayana’ actor Ravi Dubey calls co-star Ranbir Kapoor an ‘elder brother’

In a recent conversation, 'Ramayana' actor Ravi Dubey talked about his equation with co-star Ranbir Kapoor, calling him an elder brother.

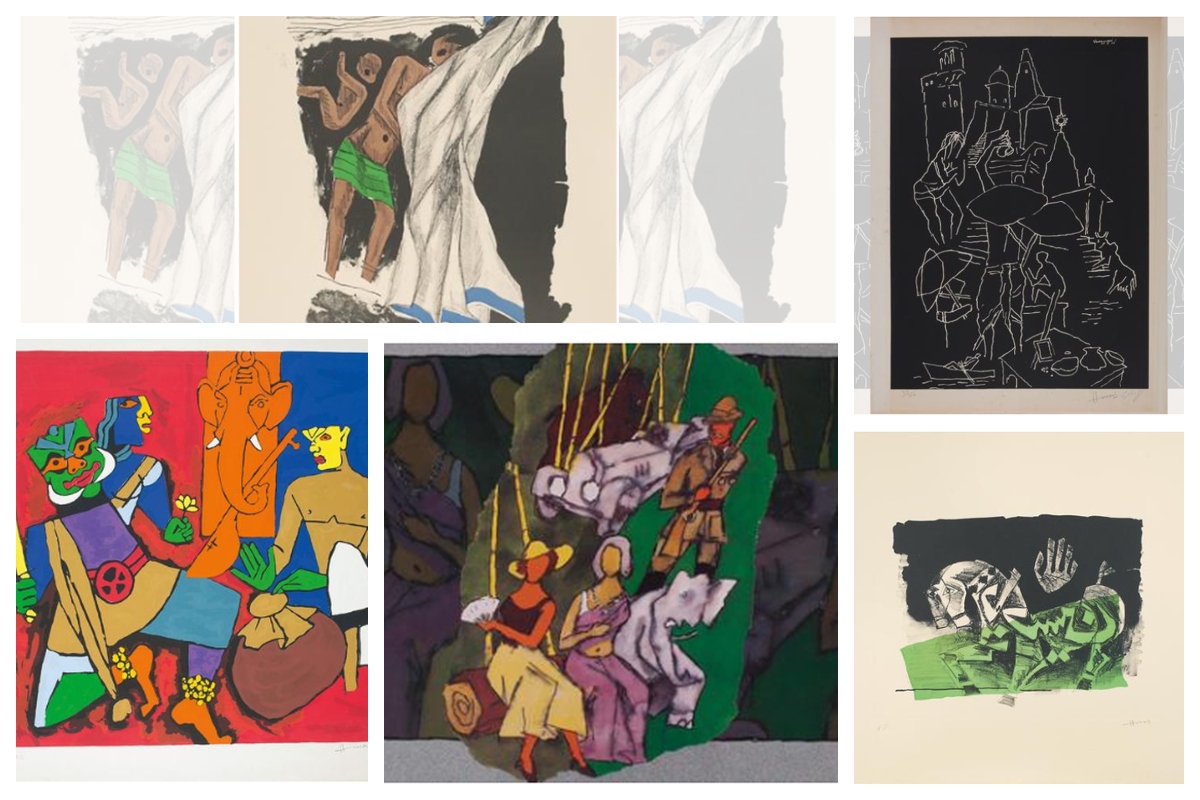

M.F. Husain is one of India’s greatest artists, whose life and works have been as celebrated as controversial. On his death anniversary, Sahapedia and DAG offer a retrospective on his contribution to modern Indian art.

( Photo: DAG via Sahapedia.org)

The depiction and development of a secular modern Indian art was one of the main concerns of iconic Indian artist M.F. Husain’s work. His language translated India’s composite culture into a rich mosaic of colours. On his canvas, the world was real, mythical and symbolic all at once.

Husain’s life was compelling—born in Pandharpur, Maharashtra, on September 17, 1913—he spent the initial days of his career painting cinema posters in Mumbai, slowly growing to be a designer of children’s nursery furniture and then becoming a member of the Progressive Artists’ Group in 1947.

Advertisement

Husain’s art reflected the world around him, his experiences and memories of people and places. The lamp and umbrella in his work are representative of his grandfather, Abdul Husain, who played a large role in the artist’s life. The lack of a maternal figure often haunted him and his work, but he found some solace in portraying Mother Teresa, in whom he found kindness and universal motherhood.

Advertisement

The toys he designed—from when he worked at the Fantasy Furniture Shop in the 1940s—would also make an appearance in his work on and off, in paintings such as Mridang and Tiger and Woman. His fascination with cinema too lasted through his career, and though a famous artist, some often mention his most notable work to be a film he made in 2004, Meenaxi: A Tale of Three Cities. His film, Through the Eyes of a Painter, won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1967.

The late 1940s and early 1950s saw Husain come in contact with a large number of artistic influences—Indian miniatures, Chinese calligraphy and Western artists. Man and Zameen—portraying the connection between the people, their roots and their culture—were both from this period. In 1954, the landmark Passage of Time marked the profuse use of horses on his canvas, which was driven by his meeting with Chinese nonagenarian artist Chi Pei She.

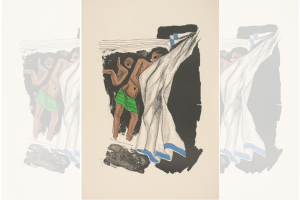

Husain began to paint the Ramayana and the Mahabharata in an attempt to connect better with the people of the country. The Ramayana series, which he painted in 1968, was taken around the country, shown to those who would not have otherwise seen such art cloistered away in faraway art galleries and museums in the bigger cities of India. In 1971, he began the Mahabharata; the monumentality of the epic translating seamlessly on his canvas. He used multiple metaphors and the narrative was dynamic even as the forms used were abstract.

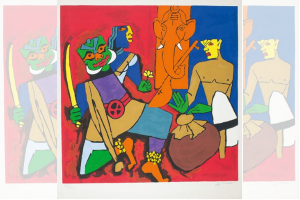

In 1967, when Husain started work on his Kerala series, it was fuelled by his keen artistic interest in the strong beliefs of the highly rigid and orthodox Namboothiri Brahmin caste of Kerala. This series was also part of his quest to understand human beings. Husain’s visit to Egypt led to him incorporate the two-dimensional structure of Egyptian art in his work and resulted in his iconic ‘Between the Spider and the Lamp’ series. Constantly learning as he travelled, the artist would even sign in various Indian languages—Hindi, Marathi, Bengali, Malayalam or Kannada.

Husain first journeyed to the ancient city of Banaras (now Varanasi) with fellow artist Ram Kumar in 1960. This resulted in a series of paintings. Both artists, deeply affected by the city and the scenes they witnessed at the burning ghats, came away to make unique paintings that reflected their individual styles and understanding of the world. Husain’s visit to Banaras led to him deciding that he would do what he wanted, paint as he liked, uncaring of how others would perceive and judge him, as criticism was rife at that juncture of his life. This was especially important since the year was characterised by scathing criticism. Remarks such as ‘Husain is finished as a painter’; ‘Zameen was hardly an original painting, Husain has put scenes together by copying adeptly from foreign magazines’ were being reported in the media.

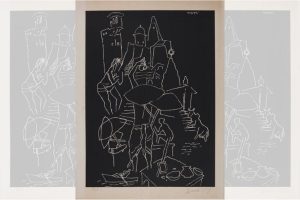

Art and politics are not independent of each other, and Husain never shied away from making statements on the state of affairs in India or abroad. Be it his humorous take on the British Raj in India, his portraits of Indira Gandhi or even his scrapbook-like sketches on newspaper cuttings of the Gulf War in the 1990s. His comment on the Iraq-Kuwait war also grew into an installation piece on torn newspaper sheets called Theatre of the Absurd in New Delhi. He was moved as much by social events as by natural calamities; Cyclonic Silence was born of his distress on seeing the effects of a cyclone that struck Andhra Pradesh in 1977.

Husain was showered with awards during his lifetime, including the Padma Shri and Padma Vibhushan. When the artist died in London on June 9, 2011, he had been in self-exile after death-threats from Hindu nationalists and court cases, having the last five years of his life between Dubai and London. Over his career, he had constantly sought to portray not just India’s culture but also her people—farmers, musicians, dancers, thinkers and philosophers. Thespian Ebrahim Alkazi, speaking about him had said in 2011, ‘For the last 60 years, Husain has been absorbing the traditions of India, its religions, its various cultures, and restating them in ways to which people have responded.’ Husain had expressed his wish to return to the country many times, but it was not to be. All through his career he had depicted India and her people, believing that the country was a ‘museum without walls’.

(This article is part of a Saha Sutra collaboration between DAG and www.sahapedia.org, an open online resource on the arts, cultures and heritage of India)

Advertisement