Sharp right turn of poll trends

Wilders’ Party for Freedom (PVV) ended up with 23.6 per cent of the vote and 37 seats in a 150-member parliament.

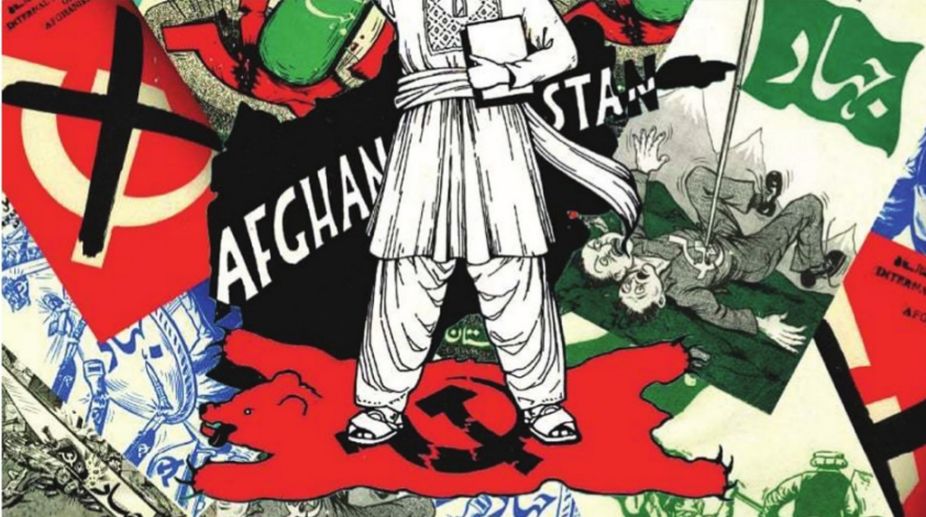

In 1985 during my second year at a state-owned college in Karachi, I befriended a guy called Yousaf. In those days I was posing as a Marxist and was associated with a progressive student organisation. But this did not come in the way of me becoming Yousaf’s friend despite the fact that he was a passionate supporter of a right-wing religious outfit.

In May 1986, Yousaf stopped coming to college. When I called his home, his father told me Yousaf had gone to their ancestral town in Punjab to attend a wedding. He didn’t sound very convincing so I asked a mutual friend about Yousaf’s whereabouts and was told that Yousaf had actually joined an Afghan insurgent group and was being trained as a guerrilla fighter on the Pak-Afghan border.

Advertisement

Yousaf returned to college in late 1986. The college administration was not amused. But this didn’t seem to bother him. He told me (and these were his exact words, albeit in Urdu), “Paracha, all that we do in the name of education in this college, and student politics is petty compared to what I have achieved … .”

Advertisement

When I asked him what was it that he had achieved, he told me that he had fought against Soviet troops in Afghanistan and that he was planning to go back there the following year. His parents, though as conservative and religious as he was, weren’t too thrilled by the idea. Yet, according to Yousaf, they had given him their blessings.

What’s more, despite knowing well that I was politically opposed to the Afghan insurgency, Yousaf wanted me to accompany him. He told me that I needed to give my life “some spiritual meaning.” To this I had replied, “How can one give spiritual meaning to one’s life by fighting an insurgency funded by the US, the Saudi monarchy and a Pakistani dictator (Zia)?”

I remember how my question had agitated Yousaf. But he still handed me two thin booklets that he had brought back with him. Both booklets were largely in Urdu but also had text in Arabic, Pashto and Dari. These were full of text praising the insurgents, telling them that they were fighting a just war against the evils of communism. The booklets also carried quotes and anecdotes of fighters who claimed that Afghanistan was “unconquerable”. At least two anecdotes in one of the booklets suggested that the insurgents had destroyed Soviet tanks by simply jumping in front of them and loudly proclaiming, “God is great!” By the way, both the booklets were published in Texas, US.

In early 1993, some five years after the Soviet forces had retreated from Kabul, I saw one of the two booklets in a government library in Karachi where I had gone to research for a newspaper story that I was doing. I had become a journalist in December 1990. This edition of the booklet was published in 1991 with an additional chapter explaining how the anti-Soviet insurgents (mujahideen) had “defeated a world power (Soviet Union).”

According to various experts who study “Islamic militancy”, widespread claims such as that Afghanistan was “invincible” and that the Soviet Union was destroyed by Muslim militants were first concocted by propagandists in US President Ronald Reagan’s administration (1981-88) and by those facilitating the anti-Soviet insurgency in Pakistan.

The experts also suggest that such claims (including anecdotes about miraculous heroics of the insurgents who were supposedly able to trigger sudden combustion of Soviet soldiers and tanks with a loud war cry) continued to be applied by various militant groups in Muslim countries, including Al-Qaeda, for recruitment purposes.

In 2011, Jonathan Steele, author and war correspondent of UK’s The Guardian published his eighth and most referenced book The Afghan Ghost. In it he shot to pieces the many claims aired during the Afghan conflict of the 1980s, and which are still being dished out by various militant groups in the Middle East, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Steele refuted the claim that the Afghans had always defeated foreign armies. He reminded his readers that in 330 BCE, Greek armies led by Alexander marched through Afghanistan with very little resistance. Then, a millennium later, Genghis Khan’s Mongol hordes demolished whatever resistance his army faced in Afghanistan.

Steele then went on to suggest that the late 19th century battles between the British and the Afghans were hard-fought but, by 1880, the Afghans had to cede various frontier areas to the British.

Steele also puts to rest the common belief that it was the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 which kick-started the civil war there. A former CIA operative and later President Obama’s defence secretary, Robert Gates, wrote in his 2015 book Duty that a number of insurgent leaders who fought against the Soviets had earlier rebelled against the “modernist” Afghan nationalist regime of Sardar Daud (1973-78). Gates also wrote that many of these insurgents were already being backed by the US and by the ZA Bhutto government in Pakistan, years before the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan by Soviet forces.

The claim which Steele takes the most pleasure in debunking is regarding the Islamic insurgents’ role in triggering the fall of Soviet communism. Steele quotes Morton Abramowitz, who directed the US State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research at the time, as saying that in 1985 there was great concern in Reagan’s White House that the mujahideen were actually losing the war. Abramowitz told Steele that the insurgents were losing major battles and “falling apart”.

According to Steele it was the new Soviet leader Gorbachev who decided to pull the plug and begin to roll back the war in Afghanistan. Steele wrote that “Gorbachev calculated that the war had become a stalemate” and was draining the Soviet economy. The Soviet economy was already under strain mainly due to failed socialist experiments. Its ultimate failure and the Soviet Union’s eventual collapse had little to do with the Soviet involvement in Afghanistan. Basically the Soviet Union imploded from within.

Yousaf went to Afghanistan again in 1987. He returned later that year and by the early 1990s he had become completely disillusioned by his earlier passions. I last met him in 2004 when he was moving to Nairobi with his wife and children. I handed him back the two booklets he had given me in 1986, jokingly telling him that he might still need to give his life some spiritual meaning.

He laughed, then ran to his bedroom and came back with an old paperback biography of Karl Marx. He took the booklets from me and handed me the Marx bio, saying, “Thanks, and here, this is for you. These booklets and the Marx bio will remind both of us about the utter stupidity of youthful idealism.”

dawn/ ann

Advertisement