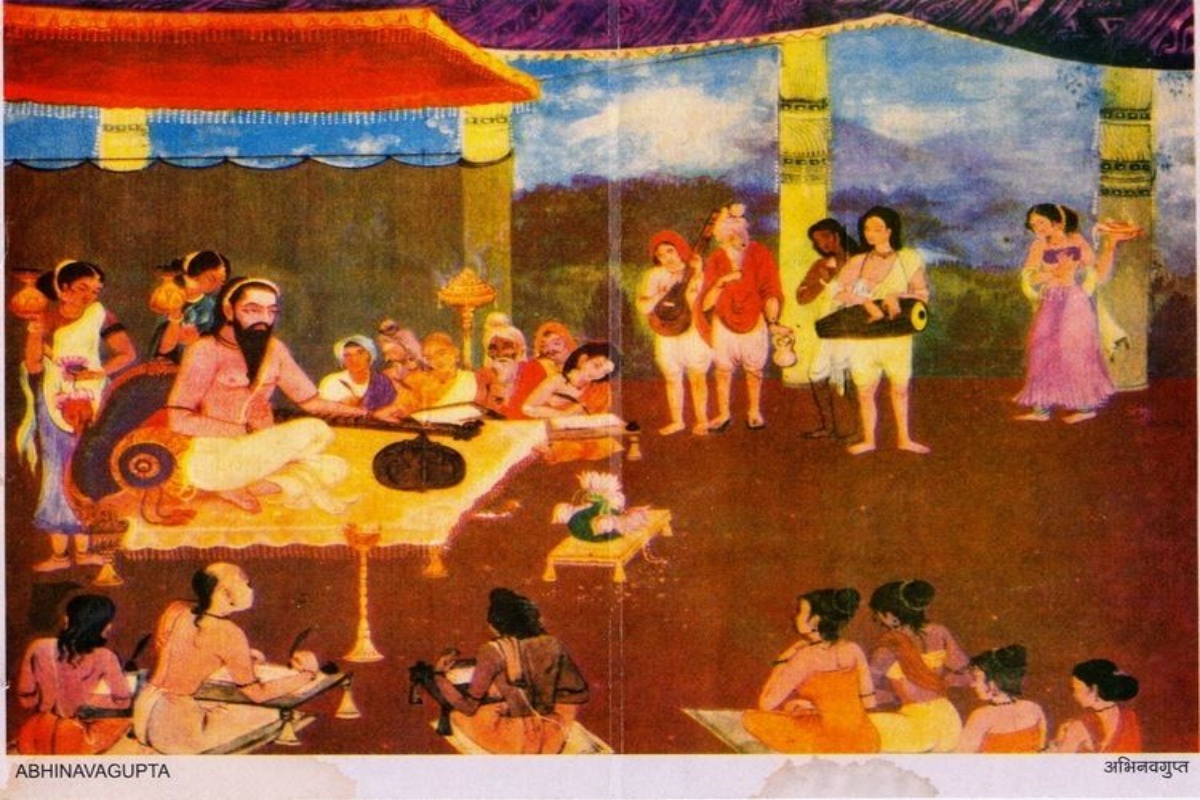

Indian intellectual systems have been greatly influenced by the ancient Kashmiri centres for theological discourse and out of these debates emerged the “remarkable” Kashmir Shaivism that assimilates the concepts of metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and aesthetics into a single entity, says techie-film historian-author Prachand Praveer, whose seminal book on world cinema has been essentially influenced by 10th century Kashmiri philosopher Abhinavagupta.

“If we look at any Indian classical philosophical system, typically it discusses four important areas such as metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and aesthetics. Kashmir Shaivism is remarkable in the sense that it assimilates the major philosophical debates such as Santana vs Buddhist, Dualist vs Non-Dualist, Impact of Grammarians on epistemology, and multiple Bhakti traditions all into one coherent system.

Advertisement

“Unfortunately, Tantric systems are out of current mainstream intellectual and philosophical discourses, whereas Abhinava Gupta assimilates all walks of life including drama and music in his assimilation and formulation of various thoughts of Kashmir Shaivism. It is important to note that Kashmir Shaivism is considered as the fruit of Indian classical philosophical debates,” Praveer told IANS in an interview.

Advertisement

How else did Kashmir contribute to the development of Indian classical philosophy?

“Indian intellectual systems have been greatly influenced by the Kashmiri mathikas (centres for discourses) and its numerous intellectual traditions. Great grammarians such as Panini (author of the “Astadhyayi”) and Pata�jali (author of “Mahabhasya”), an ancient treatise on Sanskrit grammar and linguistics, and the compiler of the “Yoga sutras”, a text on Yoga theory and practice), were Kashmiris,” Praveer explained.

He also pointed to a “long list of major contributors with a definite presence in Kashmir” such as Bhamaha (7th century), the author of “Kavyalankara”; Shiv�nanda, Vasugupta (around 800); Anandavardhana (820-890), the author of Dhvanyaloka; Kallata (around 825); Utpaladeva (900-950), the author of “Isvara-pratyabhij�a-karika” (on Tantric metaphysics); and Abhinavagupta (950-1016), the author of “Tantraloka” and “Abhinavabharati”.

Post-Abhinavagupta, there were Kemendra (990-1070), and Mammata Bhatta (around 11th century).

“I believe even today any Indian literary criticism cannot be possible without describing or citing or subscribing to the views of one of these literary techniques such as “Alamkara” or poetic decoration (attributed to Bhamaha), “Dhavni” or aesthetics suggestion (attributed to Anandavardhan), “Vakrokti” or theory of oblique expression (attributed to Kuntaka), “Auchitya” or propriety (attributed to Kshemendra) or Mammata’s propounded theory of poetic creations,” Praveer said.

He noted that an “important name” that every Indian student of music would know is Sarngadeva (1175-1247) who authored “Sangita Ratnakara”.

“He was born in a Brahmin family of Kashmir and was not living in Kashmir, but we do see the impact of Abhinavagupta and other Kashmiri traditions on his famous treatise of music. Needless to point out that his authoritative treatise on Indian classical music is revered by both the Hindustani music and the Carnatic music traditions,” Praveer said.

Any other examples of how Kashmiri intellectuals have preserved Indian thoughts?

“Well, India in its intellectual curiosity and discipline has preserved her heritage in many strange ways. Abhinavagupta’s commentary on Natyashastra, the ‘Abhinavabharati’, was discovered in Kerala in the early 20th century. Without his commentary, our understanding of Natyashastra would have been very shallow.

“Indian classical traditions always include the additions in shlokas as “prakshipta” (projected addition) if found not matching with the current version. If you happen to read the Valmiki Ramayana or Mahabharata in any authentic preserved version, you will encounter such additions with commentary that it has been added by some sources which is not approved but yet present for the sake of completeness.

The Bhagavad Gita occupies a unique place in the annals of Indian thought and culture through the ages and in this sphere too, Kashmir claims its share of originality.

“The existence of Kashmir recension of Gita was first drawn by (German philologist) Dr (Friedrich) Schrader as back as 1930. The Kashmir recension of Gita contains 745 verses as against 700 verses of the popular recension adopted by Adi Shankaracharya. Abhinavagupta’s commentary, under the title ‘itaarthasangraha’, explains the fight between Kauravas and P�ndavas is symbolic of a war that is constantly raging between the lower and upper impulses of our personality,” Praveer explained.

Once upon a time, Buddhism was a major philosophical movement in India. Was there any Buddhist connection to Kashmir intellectual traditions?

“Yes. Kashmir, from early times, has been a meeting ground of a variety of faiths and divergent thought currents. Kashmir’s attachment to Buddhism dates back to the time of Ashoka (273-232 BC). N�gasena (150 BC), the author of ‘Milind-Panho’, is said to be a Kashmiri. Kanishka (78-102) convened the 2nd Buddhist Council in Kashmir and brought Ashvaghosha to act as its Vice President.

“It has been noted that Kashmiri monks were active in medieval China from the early fourth century up to the 11th century. Kashmirians’ contribution, at large, includes translations into Chinese of Buddhist canons and ritualistic texts,” Praveer said.

His book, “Cinema Through Rasa – A Tryst with Masterpieces in the Light of Rasa Siddhanta”, released earlier this year, unravels the nuances of world cinema by harkening back to Abhinavagupta as it pays tribute to his commentary on the “Natyashastra” and the concepts of “Rasa Siddhanta” (theory of aesthetic experience) and “purusartha” (cultural value system of life-pursuits).

Advertisement