Cruz and Banderas united by humor in ‘Official Competition’

In “Official Competition”, Lola acts as a referee, but also as a sparring partner, inciting confrontation between the two actors.

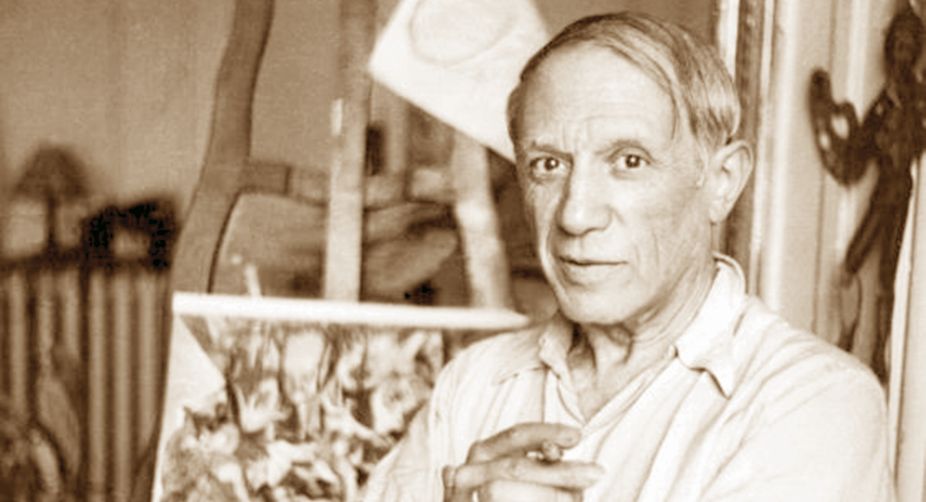

Antonio Banderas grew up in the same Spanish town as Pablo Picasso. Now, the actor finally gets to play his childhood hero — and defends the painter against accusations of misogyny.

Antonio Banderas as Pablo Picasso

By the time Antonio Banderas shaved off his eyebrows and hair to play Pablo Picasso – his lifelong hero, his towering standard of greatness — he had already been asked to portray Picasso twice. “Oh, yes,” he said, “twice before.” He sits in a director’s chair, his face contorted into a thoughtful expression, complete with chin strokes.

On his nose, cheeks and chin, he wears silicone prosthetics for the features he does not share with Picasso: to thin out his featherbed lips, to make his nose fleshier and his jowls heavier to mask his beautiful face. It doesn’t work. The minute you look at him, his chocolate pudding swimming pool eyeballs give him away.

Advertisement

It is his last day here before heading to Malta for the final leg of shooting for Nat Geo’s Genius, an anthology series that focuses on Picasso in its second season. The Picasso he is playing today is 67.

Advertisement

When he is shooting, he assumes the posture of a 67-year-old, but when he isn’t, he is Antonio Banderas, a human exclamation point, his face an orchestra of intense expressions. (A better way to put it: his friend Salma Hayek told me that out of all the characters he’s ever played, he most resembles Puss in Boots in real life.)

Oh yes, by the time he shaved off all vestiges of hair above his neck, he already had a long, full career. He was already a star of great renown in Spain, where he had served as a muse to Pedro Almodovar for seven movies.

He had already received accolades for his performance in 1992’s The Mambo Kings, a performance so openhearted and passionate that few noticed that his only English at the time was in the form of phonetic imitation. He had already wooed US audiences with his intimate portrayal of Tom Hanks’ lover in Philadelphia.

He had helped Robert Rodriguez, another director who loved him achieve US acclaim via Desperado and the Spy Kids movies. He had swashbuckled his way into children’s hearts as a sultry, shod cat in the Shrek spinoff, Puss in Boots.

He had directed two movies. He had serenaded in Evita and simulated French-kissing with Catherine Zeta-Jones through two of the most alive iterations of Zorro we’d ever seen. He had seduced his way to a Tony nomination for an energetic Nine. He had Angelina Jolie as co-star in Original Sin.

He was a beloved fixture in US cinema – a masked avenger, a Latin lover, a mariachi, a matador, an assassin posing as, oh yes, a mariachi. He bided his time in masks, with guns, with swords; as he grew older, he was rewarded with the chance to play (or almost play, in projects that got killed) historical figures: Dali, Mussolini, Pancho Villa, and Picasso – and Picasso.

And now it is finally happening. He is going to play his boyhood hero and bring pride to Málaga, Spain – both his and Picasso’s hometown. When Banderas was growing up, his mother would stop in front of the house the artist was born in every time they passed it and say, “Look, Antonio”. Now, in the home he owns in Málaga, he can see that house from his terrace.

All this, and still, when Banderas sits down in a director’s chair next to me, after I congratulate him on what must be a significant lifetime achievement, he shakes his head and says I have it wrong. Sure, it’s great, this work is great. But it’s not the ultimate. Not yet. “Oh, no,” he says, leaning in close.

“I still don’t think I have done the thing I will be remembered for.” He is dressed for the day’s scenes in a tank top under a silk button-down shirt and trousers hiked up to around his fourth rib, a particular kind of European old-man fashion.

He wears over his bald head a sparse netted gray wig, since Picasso had Dr Phil pattern baldness and Banderas still has a full head of hair. He could have worn one of those rubber caps, but if you think he would, you don’t know Banderas. He would always take the opportunity to come even closer to the character.

He considered Picasso special. They started out so similar, but it’s easy to confuse details of birth with the way a man turns out. Take their treatment of women, for example. Hayek says that Banderas is such a good friend that when he read her essay in The New York Times about being harassed by Harvey Weinstein, he was among the first to call her.

He wanted to know why she didn’t tell him what Weinstein was doing back when Banderas was making a cameo in her movie Frida. He was the first person to call the minute she was nominated for an Oscar for the role.

Picasso, on the other hand, said that “women are machines for suffering” and that, to him, they were either “goddesses or doormats”. Genius: Picasso addresses the artist’s misogyny as much as his art.

In the first episode a woman is home with his offspring while he makes out with another lover on the beach, and both women get in a fistfight in front of him while he is painting Guernica. Honestly, I tell him, the lionisation of a man who treats women this way is gross to me.

Banderas beseeches me to be more generous. “The problem with Picasso from my point of view, I don’t think he abused women, as we understand that now,” he says. “The problem is that he wanted everything, everything, all the time.”

He enters a project with maximum dedication, maximum research. The more you know about a character, the more you can fill the white spaces with something rich. He asks: do you know that Picasso’s grandson Pablito apparently stood on a street near his home in France with a sandwich board when his grandfather wouldn’t allow him to visit him in the final days? Go ahead, ask him anything.

If you know your subject down to his soul, then the subject is there when you need him. “I’ve been with him now for months every day, and I can just actually say, ‘OK, come over here’. The ghost comes and just gets in your body and you’re… ‘boom’.”

On the days it doesn’t come so easily, you can fill the white space with you. Who is to say where Picasso ends and Banderas begins? Who can give that information now that he’s prepared for this role three separate times? Kenneth Biller, a creator of the show, and Ron Howard, an executive producer, immediately thought of Banderas for the role.

They worried that they’d have to persuade him to play the part, but he jumped up (pop!) and agreed to do it. He had recently happened upon the first season of Genius, with Geoffrey Rush as Albert Einstein, while cruising on his Apple TV. He watched the whole thing in two days.

Genius: Picasso, which takes place over 10 episodes, is shot during two eras: Picasso’s youth, and his old age. In his younger days, he is played by Alex Rich, who does a Picasso impression that is actually an Antonio Banderas impression.

The camera follows Rich to show the freneticism of youth. But during the old age scenes, the camera stays still, like a portrait with Banderas entering and leaving it. In those scenes, it’s Banderas who supplies the energy.

The Independent

Advertisement