There are any number of systematic psychographic studies in the US context that investigate the dispositional traits of demagogic and political leaders that are often put to use to convincingly sway the voters and curry favours – favours that often cost and defeat human logic, as perhaps happened when Donald Trump won his Presidential election.

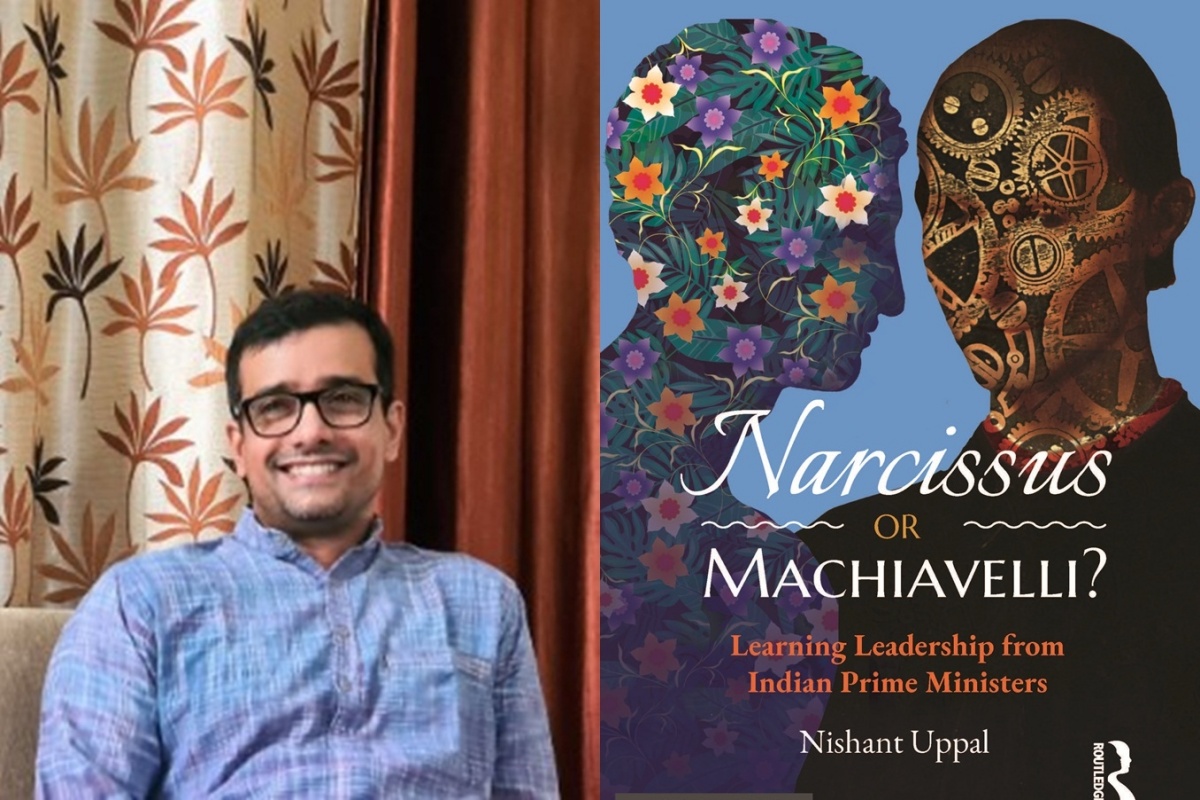

“Indian political leaders have rarely been put through this scrutiny, a startling and disconcerting fact” that prompted Nishant Uppal, an Assistant Professor in the faculty of Organisational Behaviour in IIM-Lucknow’s Human Resources Management Group, to write his seminal book, “Narcissus Or Machiavelli, Learning Leadership From Indian Prime Ministers” (Routledge).

Advertisement

“Another such trigger was Cambridge Analytica’s fiasco where people’s voting choices were swiftly manipulated using subconscious cognitions by data analysts in a liberal democracy. These analysts guide principalities about their exteriors, verbal gestures, and even symbols such as self-named embroidered suit in order to woo the followers.

Advertisement

“India with more than a third of its population with access to internet and smart phones thus becomes naturally vulnerable to data analytics firms and their benefactors,” Uppal told IANS in an interview, adding his aim of writing the book is to “sensitize the Indian commoners and voters for their susceptibility for such manipulations specially when utilized by their chosen superiors (read political leaders)”.

“While, the Prime Minister’s personality clearly operates as a critical indicator of his/her socio-political, economic, and international policy decisions, there are multiple challenges in assessing political leaders’ personality. Political leaders are physically distant and often unavailable for controlled laboratory-based experiments.

“The second challenge lies in selection of a widely acceptable theoretical apparatus that can provide unbiased insight on leaders’ personality characteristics. Finally, a third and unanswerable challenge exists in the associated paradox. Identification of demagogic characteristics in political leaders has an inherent existential threat to their propagandist approach.

“Demagogues thrive on the ignorance of their followers. Therefore, such exposure of their weaponry will potentially disarm them from strategic viewpoint. However, this systematic risk in such intellectual pursuit is unavoidable,” Uppal explained of his research, using historiometric analysis, a study of personal characteristics that has been traditionally employed to assess the personalities of eminent world leaders and their effect on the constituents they lead.

“Further, Machiavellianism and Narcissism are two personality traits that have emerged as legitimate frameworks for studying policy-personality connect and demagogic tendencies in political leaders. I have used these two as indicators of Prime Ministers’ demagogic and propagandist approach, if any and to what extent,” Uppal added.

What then, does the book deliver as it analyses nine of India’s 15 Prime Ministers � Jawaharlal Nehru, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Indira Gandhi, Morarji Desai, Rajiv Gandhi, P.V. Narasimha Rao, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Manmohan Singh and Narendra Modi. Gulzari Lal Nanda, who was an interim Prime Minister, has been excluded, as have been Charan Singh, Chandra Shekhar, V.P. Singh, H.D. Deve Gowda and I.K. Gujral, who “practically and perceptibly did not possess any influential authority in office”, Uppal writes.

“Nehru scores high in narcissism and Machiavellianism based on his mentor-protege relations, style of administration, nature of nationalism, image consciousness, and awareness of and reaction to popularity.

“Shastri scores low in all parameters except in the case of image consciousness.

“Indira Gandhi scores high in terms of all parameters, namely strong ambition, mentor-protege relations, style of administration, nature of nationalism, image consciousness, popularity and reaction to it, and the freedom of press.

“Desai scores high in terms of one parameter, which is ambition.

“Rajiv’s scores show the presence of narcissism and Machiavellianism in terms of style of administration, image consciousness, freedom of press, and popularity and reaction to it.

“The observation of these parameters in the case of Rao show high levels of both traits in terms of ambition, moderate in style of administration, and high levels of Machiavellianism in his treatment meted out to the press.

“Vajpayee’s scores are moderate in terms of ambition and style of administration and high in terms of popularity and awareness to it.

“(Manmohan) Singh scores low in most categories except in terms of freedom of press, where his actions and personality can be read as moderately narcissistic.

“Modi again scores high in both traits based on all parameters, including ambition, mentor-protege relationship, style of administration, nature of nationalism, image consciousness, popularity and freedom of press,” Uppal writes.

“Thus, it can be observed that the number of parameters that suggest the presence of narcissistic and Machiavellian traits are seven in Modi and Indira (Gandhi), five in the case of Nehru, three in the case of Rao and Vajpayee, four in Rajiv (Gandhi), and one in case of Shastri and Desai.

“It can, therefore, be concluded that the prime minister with the maximum number of matching parameters has the highest presence of narcissism and Machiavellianism traits and similarly the one with the lowest number has the lowest presence of these traits,” Uppal writes.

Following this scale, Indira Gandhi and Modi “show the strongest presence of narcissism and Machiavellianism” while Shastri and Desai “show the lowest”, Uppal writes.

The lessons from the book � and for future leaders – can be drawn according to the purpose of the audience, Uppal said during the interview.

“Each of our Prime Ministers exhibited several distinct and some common features. The reader of this book will know the sources of unforgettability of Nehru and characteristics that made Narasimha Rao a forgotten Prime Minister. Nehru’s popularity as Prime Minister among masses though is unmatched, Modi is constantly striving to overcome Nehru’s �gold medal position’ in this regard.

“Similarly, one would be appraised of inconsistency between Vajpayee’s dispositions and India Shining campaign that failed to deliver and eventually led to disastrous defeat of his party. Also, one may see to what extent genetics transmitted across Nehru’s pedigree,” Uppal said.

Additionally and equally importantly, are the messages are inherent for the upcoming leaders “about what characteristics potentially may lead to sustenance in leadership positions”.

“For example, while, Vajpayee and Narsimha Rao, both were tolerant and valued leaders, they were forsaken by Indian voters within one term despite their noticeable accomplishments. Contradictorily sometimes the traits that lead to sustenance are counterproductive, such was the case of erudite Manmohan Singh,” Uppal explained.

“While, Machiavellianism and Narcissism traits are inevitably present in all individuals, especially leaders, they have both bright and dark sides. Readers must observe and appreciate a neutrality in this work. The historiometric appraisals of Prime Ministers deliver a colossal measure of vitality, which can take a country as diverse as India, a long way past their stipulated goals.

“It intrigues citizens and lawmakers to re-evaluate their demeanours on intangible resources and to begin perceiving that human capital may bring out the difference between irrelevance and brilliance, and excellence and mediocrity,” Uppal concluded of what he termed “only a scholarly endeavour and an apolitical work of art with a neutral theoretical lens”.

Advertisement