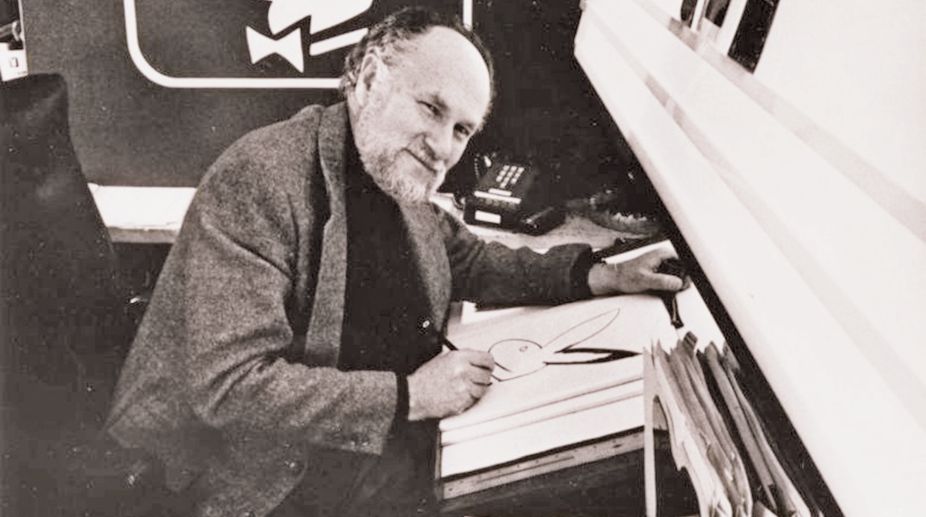

Art Paul, a graphic artist who helped Hugh Hefner define the look of Playboy magazine from its inception by drawing its rabbit logo and hiring great illustrators to lend worldliness to its pages, died on 28 April in Chicago. He was 93. Suzanne Seed, his wife, said the cause was complications of pneumonia. Paul was a freelance graphic artist with a studio in Chicago when Hefner met him in 1953, several months before Playboy’s first issue.

“He comes in and sees all the things on the wall – the commercial stuff I was doing as well as the more personal things – and he says, ‘Is that your work or work you like?’ And I said, ‘It’s both,’” Paul said in an interview with the director Jennifer Hou Kwong for her coming documentary about him, Art Of Playboy.

Advertisement

Paul quickly became the fledgling magazine’s art director as it shifted from its original name, Stag Party (which was dropped before its debut), to Playboy. He designed the inaugural cover, a photo of Marilyn Monroe set against a stark white background, and replaced the original logo (a stag in a smoking jacket) with a silhouetted rabbit wearing a tuxedo bow tie.

The rabbit later became the symbol of the Playboy empire. But Paul, who sketched it in an hour, intended it only as a stylised end point to articles. Soon after the magazine’s debut, the rabbit appeared on every cover overseen by Paul. To challenge readers, the rabbit head was sometimes embedded in the design of the covers, just as the celebrated illustrator Al Hirschfeld hid the name of his daughter, Nina, in his drawings.

Taking his cue from the subtitle of the magazine – “Entertainment for Men” – Paul focused on giving a distinctive, masculine character to its editorial content.

“The ‘entertainment’ word is really the one that sparked me,” he said in an interview in 2009 with the alumni magazine of the Illinois Institute of Technology, which merged with the Institute of Design while Paul was a student there. He added: “The word ‘playboy’ is not a serious one. The rabbit is not serious; it was basically a signal that we could make fun of ourselves.”

Paul had complete freedom to lay out Playboy’s pages, choose the typography, arrange the photographs and, critically, hire the artists. In pursuit of idea-driven illustrations, he commissioned work from Andy Warhol, James Rosenquist, Salvador Dalí, Brad Holland and many others. Having been raised and educated in Chicago, he had an affinity for local artists like Ed Paschke, Leon Bellin and Franz Altschuler.

“Paul understood that the balance between nude photography and sophisticated writing was the key to separating Playboy from a pulp girlie magazine,” Steven Heller, co-chairman of the design department at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan, wrote in an email. “So he balanced the literary aesthetic of The New Yorker with the visual audacity of Esquire and created a format that evoked both seriousness and playfulness.”

Holland, who began illustrating Ribald Classics stories for Playboy in 1968, said Paul preferred artists who had something to say. “He wanted pictures to augment, rather than illustrate, articles,” he said by email, “and that opened the door to popular culture to many of us who might otherwise have gone into fine arts.” Among Paul’s innovations were pop-ups, pull-outs and die-cut patterns that could engage readers more than standard pages.

Arthur Paul was born on the southwest side of Chicago on 18 January 1925. His parents – William, an egg candler who died before Art was a year old, and Becky (formerly Goldenberg), a homemaker – were Ukrainian immigrants. His mother did not speak English well, and his older brother, Norman, became his artistic guide. “He was a very talented artist himself,” Paul told The Chicago Tribune in 2015, “and he taught me how to look at the world around me.”

Paul filled the margins of books at home with his drawings and painted murals at Sullivan High School. While there, he also took summer classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. An opportunity to attend the school full time on scholarship was deferred while he served stateside in the Army Air Forces. But when he returned he enrolled at the Institute of Design, known as the Chicago Bauhaus. He left one course short of graduation.

Paul was illustrating books and magazines and working for clients like Marshall Field when Hefner, at the suggestion of a mutual friend, called on him about Playboy. Paul stayed at the magazine for 29 years before retiring as a vice president to pursue his own projects.

In 2009, Hefner (who died last year) paid tribute to Paul, telling the Illinois Institute alumni magazine, “Quite simply, he was the right guy in the right place at the right time. I couldn’t have done it without him.” In addition to his wife, Paul is survived by his sons, William and Fred; a stepdaughter, Nina Kohl; and two grandchildren. His first marriage ended in divorce.

In his post-Playboy years, Paul drew and painted. Fascinated by human faces and inner states of mind, he specialised in surreal, fanciful and distorted portraits of heads. As he was nearing his 90th birthday, he allowed his wife to catalogue his works so they could be exhibited, as they were at the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art in Chicago and the Coda Gallery in Palm Desert, California.

He continued making art even as he was gradually losing his vision to macular degeneration. “He was losing his sight and was getting dementia and aphasia, and started sketching whimsical and philosophical drawings,” Seed said in a telephone interview. “He didn’t want to stop. He did funny things, not quite abstracts; you could see figures in a certain way, like a chicken.”

And, she said, he made lighthearted concessions to his loss of sight. “He was excited to have visions that people with macular degeneration have, like a phantom limb,” she said. “He would jiggle his head and say, ‘I can turn one person into a crowd.’ That just took my breath away.”

The Straits Times/ ANN Photo credit: The New York Times