Parents and children in east of India still willing to buy and read books: Survey

Children’s books are selling like hot cakes at the International Kolkata Book Fair at Boimela Prangan in Salt Lake.

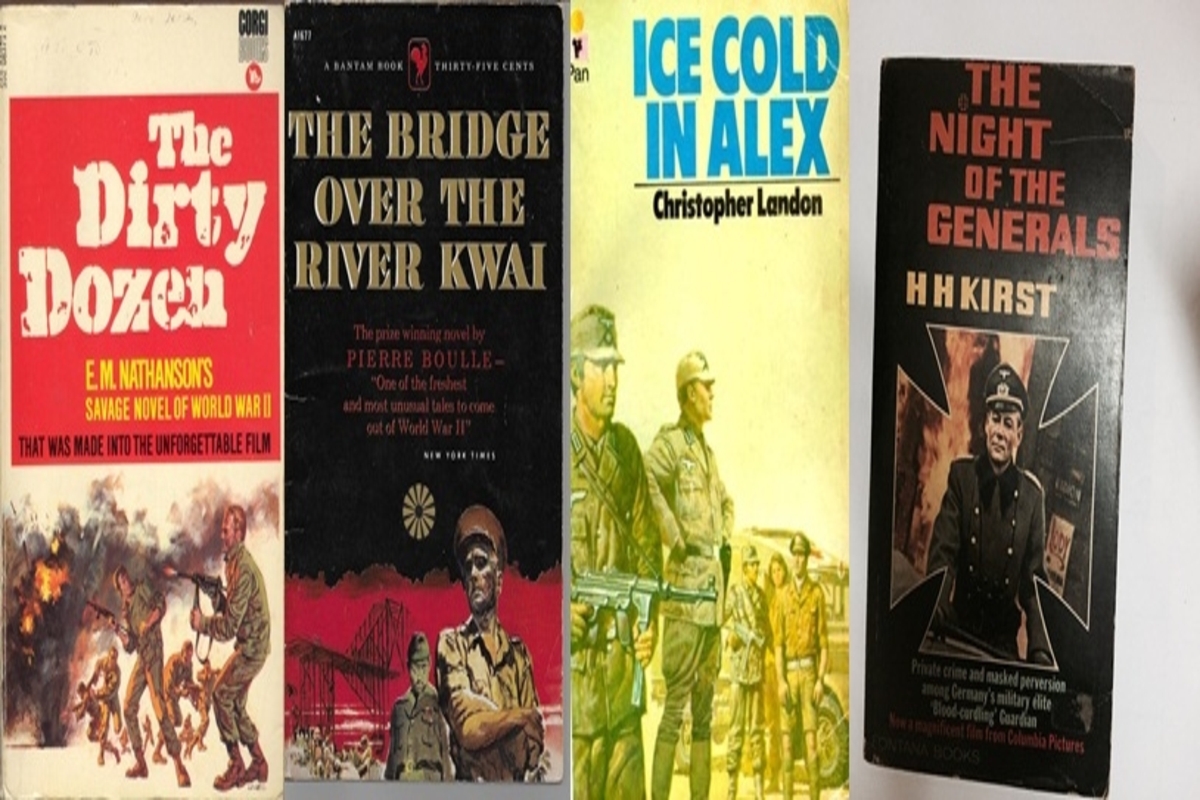

There are more examples of divergences, but let’s now look at another half-a-dozen war books and their film adaptations, which are lesser-known, but deserve both reading and viewing.

Battling Inspiration: Top WWII films and the books behind them. IANS

The ‘egg or chicken’ conundrum is not required to establish whether books or films came first, but it is indisputable that a whole host of blockbuster movies — from the James Bond to the Harry Potter series, from “Dracula” to “Gone With the Wind”, and from “Ben-Hur” to “Jurassic Park” — owe their origin to books. War movies are no different.

A constant occurrence in human affairs from the earliest time, wars, given their effect on a society’s present and the future, the sacrifices they demand, and the moral issues they raise, figure in all forms of literary works. With the advent of cinema, their cultural depiction got a new — and much wider — display.

Advertisement

Since the First World War, war films of all shades, from jingoistic to pacifist, have been a staple of global cinema, being made right even as the conflict they depict rages on, down till the present day. Cinema traditions across the Americas, Europe and Asia have their masterpieces, but it is Hollywood, whose sheer scope and influence makes it predominant, that is most known for its repertoire.

Advertisement

While it has filmed a wide swathe of wars down the ages and around the world, from the Trojan War to the War against Terror, as well as some lesser-known conflicts (the 15th Moorish-Christian battles in Spain known as ‘El Cid’), the pride of place belongs to those set in the Second World War.

But, be they broad-spectrum retellings of major battles like the D-Day (“The Longest Day”, 1962), or the Battle of Arnhem (“A Bridge Too Far”, 1977), or episodes of PoW breakouts such as “The Great Escape” (1963), focused experiences of smaller formations (“Cross of Iron”, 1977, or “Squadron 633”, 1964), or even varying degrees of fiction (“The Bridge on the River Kwai”, 1957, “The Dirty Dozen”, 1967, “Where Eagles Dare”, 1968, and “The Eagle Has Landed”, 1976), all are based on books. Also, most made the transition from the page to the big screen in a considerably short span of time.

Irish-American journalist Cornelius Ryan’s eponymous military histories, which draw on the experiences of as many survivors as available from all sides, came out in 1959 and 1974 — three years before the films based on them; American author E.M. Nathanson’s “The Dirty Dozen” came out two years before the film; and Scottish novelist Alistair Maclean’s “Where Eagles Dare” and Jack Higgins’ “The Eagle Has Landed” just a year before.

There was, however, a lag for “Cross of Iron” based on German author Willi Heinrich’s “The Willing Flesh” (German 1955, English 1956), “Squadron 633” on former RAF officer Frederick E. Smith’s 1956 book of the same name, and most for Australian fighter pilot-turned-author Paul Brickhill, whose work on the PoW escape — of which he had first-hand experience — came out in 1950.

Brickhill, however, is unique in having two other works become successful films — “The Dam Busters”, based on an RAF bombing raid on German industry (book, 1951; film, 1955) and “Reach for the Sky” (book, 1953; film, 1956), on the disabled British fighter ace Douglas Bader.

But there are major differences between the printed and the reel versions. Some are due to the limitations of the form, say, the need for a condensed narrative, or the inability to delve into the background or to represent the thought processes of a character on screen, but most are instances of artistic licence, driven by the need to create a compelling or dramatic scene even if it is made up.

In “The Longest Day”, the scene showing a group of French nuns, led by the Mother Superior no less, hurrying into a war zone to minister to their injured compatriots makes for splendid viewing, but never happened in real life. Then, at the end of “A Bridge Too Far”, the actor playing the role of a British General, who masterminded the campaign, is shown speaking the phrase from which the book and the film’s title is drawn — he did say that but at a different point, in another context. Then, the motorcycle chase towards the end of “The Great Escape” makes for thrilling viewing, but never happened in real life.

Political and commercial reasons may also play a role in changes. “The Great Escape” was heavily fictionalised, with all its protagonists being composites of the real-life inmates and their roles jazzed up for the stars playing them. American officers, moreover, were given prominence, despite the fact that the PoWs who broke out were British and other Allied personnel.

The Americans were involved in planning and preparations for the escape, but their entire contingent had been moved to a different camp more than half a year before the escape.

On the other hand, some of these books do not make it easygoing for the filmmaker.

“The Dirty Dozen”, the film that is, shows the selection and training of the personnel for about two-thirds of the running time and the operation in about the final third. Guess, how much the book, over 500 pages in most editions, devotes to the denouement? Just the last two dozen-odd pages, with most of this being a report for the general concerned, and spending the rest as a character study. You won’t even recognise most of the film’s ‘Dirty Dozen’.

There are more examples of divergences, but let’s now look at another half-a-dozen war books and their film adaptations, which are lesser-known, but deserve both reading and viewing.

Less known than his contemporary Nicholas Monserrat of “The Cruel Sea” (1951; film, 1953), British naval officer-turned-writer Denys Rayner’s “The Enemy Below (1956; film, 1957) is a fictional but authentic tale of a cat-and-mouse game between an Allied destroyer and a German U-boat somewhere in the South Atlantic Ocean, spread over five days and ending with both in the same boat (figuratively and literally).

On land, much drier land, is British novelist Christopher Landon’s “Ice Cold in Alex” (1957; film, 1958), about two British soldiers and two nurses, pulling back after an advance by Field Marshal Rommel’s Afrika Corps, getting separated from their convoy, and forced to make the arduous drive across the desert to safety.

While Joseph Heller’s “Catch-22” (1961; film, 1970) is the defining satirical novel of World War II, American novelist William Bradford Huie’s “The Americanisation of Emily” (1959; film, 1964) is a no less barbed look at how some officers will go to any extent to achieve glory, even as some seek to avoid it at any cost.

German novelist Hans Helmut Kirst’s “The Night of the Generals” (1962; film, 1967) is the incongruous tale of a dogged German military policeman seeking to catch a serial murderer of prostitutes, believed to be one of the three generals in the vicinity, even as indiscriminate massacres go on all around.

Start with these and note the differences.

Advertisement