KMC chasing Mahalaya deadline for road repairs

With the ‘puja mood’ setting in among Bengalis, the Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) is trying to make the most of the ongoing dry spell for repairing roads.

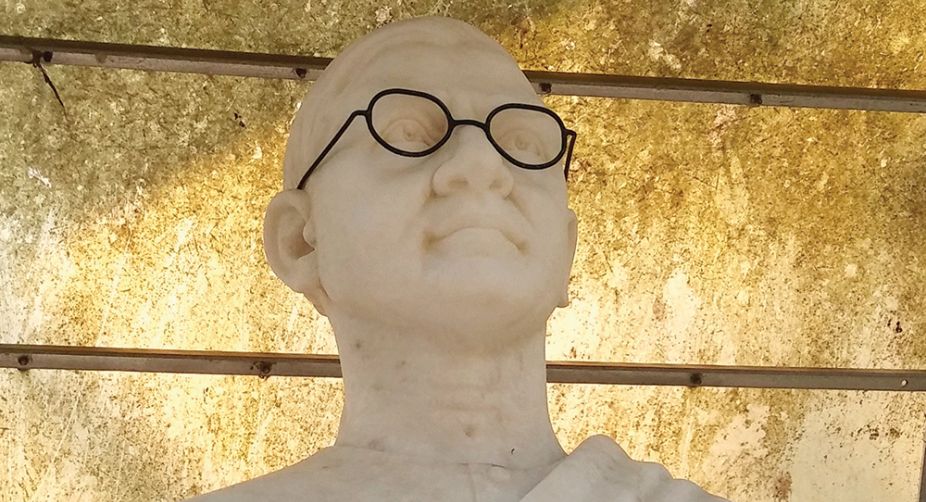

Ruby Palchoudhuri, Advisor and President Emeritus, Crafts Council of West Bengal, talks about the Gurusaday Museum near Joka, named after the brilliant Gurusaday Dutt, which is now closing down. Excerpts from an exclusive interview.

Ruby Palchoudhuri, Advisor and President Emeritus, Crafts Council of West Bengal.

The Gurusaday Museum at Joka has a collection of around 3,300 exquisite exhibits of folk arts and crafts, which capture much of Bengal’s creative heritage; much of it personally collected by the remarkable Gurusaday Dutt, ICS (1882-1941).

A glimpse of his personal brilliance: having secured the first place in the Entrance Examination in Assam Province in 1899 and in the F. A. Examination from the Presidency College of Calcutta (1901), Dutt went on to secure the first position in the ICS.

Advertisement

Examination in 1905 along with a first in Constitutional Law at the Bar-at-Law Examination, which is “a world record”. A servant of the Raj, he nevertheless stayed in touch with the revolutionary leaders of Bengal but, more importantly, he devoted himself to preservation of Bengal’s creative heritage with a passion that knew no bounds.

Advertisement

Q. Not too many know much about Gurusaday Dutt or his remarkable work. We are on the verge of closing the museum named after him…

There were very few more enlightened Bengalis than Gurusaday. The preceptors must have been kind to him for Gurusaday (meaning ‘Favoured by the Guru’) Dutt would not otherwise have risen far above his already enormous stature as an ICS and taken upon himself the creative stewardship of Bengal’s remarkable crafts.

Regrettably, not much is discussed about him in contemporary creative dialogue but, as Kobiguru Rabindranath said, it was Gurusaday’s driving force that facilitated the building of Vishva Bharati. Gurusaday Dutt, I.C.S., was then the district magistrate of Birbhum.

He was supported by his equally exceptional wife, Saroj Nalini Dutt, passionately committed to social work. She started Mahila Samitis (Women’s Institutes) as early as 1913, at Pabna district in British India, where her husband was the District Magistrate at that time.

Indeed, rural Bengal inspired both of them. As Dutt worked for the development of the district, he was overwhelmed by the region’s crafts and, by the end 1920s, he had emerged as a collector of both visual and performing traditional art heritage of undivided India.

These later went into the creation of the Gurudasay Museum. As far as the performing heritage was concerned, he formally founded the Bratachari Movement that still lives on, though largely in Bengal’s countryside.

Those were the days when political leaders were stalwarts in more ways than one and support to perpetuate Gurusaday’s remarkable legacy came from none other than the then Union Minister of Education, professor Humayun Kabir. The Museum of Folk Arts and Crafts was set up in 1963 and named after him.

Q. He is rarely acknowledged today, but in his lifetime?

In his lifetime, every creative luminary and nationalist leader looked at him with awe, from Mahatma Gandhi to Rabindranath and Abanindranath Tagore.

They did not have to come from Bengal, Chakrabarty Rajagopalachari, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Stella Kramrischand so many others expressed their wonderment at this passion, enthusiasm, love and energy around the creative sector that was being allowed to die a slow death then.

Gurusaday Dutt managed to turn it around as he injected vitality into Bengal’s folk art, to what is called the neo-Bengal school of art.

Q. Tell us about the Bratachari Movement.

The Bratachari movement was a formalisation of Bengal’s existing folk culture that happened under the guidance of Gurusaday Dutt. It is both a spiritual and social movement that Dutt hoped would deepen the inherent faith in the oneness of man and nature, the oneness of mankind itself and strengthen India’s moral fibre.

He sought to deepen the national awareness among people, irrespective of caste, religion, sex and age through use of folk culture around use of mind and the body, through dance and music and built around labour, truth, unity and joy.

Indeed, so powerful was this movement that even the Europeans were impressed by its reach and beauty. Bratachari societies came up all over Bengal -east and west; they celebrated farming, healthy living, dignity of labour. Who can forget lilting rhythm of “Chol kodal chalai”?

Q. He is believed to have revived some important dance forms too?

He started a Folk Dance Revival Society at Mymensingh but he actually revived the Jaari dance, being inspired by its secularity that he deemed important at an age when communal tensions were overtaking society.

He is also reputed to have rediscovered the Raibeshe folk dance, a martial dance of undivided Bengal, in Birbhum in 1930. He is also reputed to have delved into origins of the martial dance form and found its links with the army of Raja Man Singh of Rajasthan. His contribution to the revival of the Kaathi, Dhamail, Baul, Jhumur, Brata and Dhali dances from across the Bengali cultural landscape is legendary.

Reportedly, his examination of the dance forms took him to the All-England Folk Dance & Folk Song Festival; meeting Cecil Sharp, who revived Morris dancing in England, when he visited London around 1931. He set up the Bangiya Palli Sampad Raksha Samiti (Society to Protect the Cultural Heritage of Bengal) on his return.

There were many other institutions that he set up. Fortuitously, his tenure as District Magistrate of Bankura in 1924 had given him enough exposure to do such remarkable work around the region’s heritage. Most of his collections came towards the end of that decade. Most of it is available in the museum though not all are displayed.

Q. How was the museum started?

Gurusaday Dutt had possibly formally bequeathed his collection to the Bengal Bratachari Society that he had founded. He had also built a very nice house on the outskirts of the city, probably to get away from the madding crowds.

It served as the ideal place to keep his collections though it took some two decades to have it converted into a formal museum. It was inaugurated by Bidhan Chandra Ray, then Chief Minister of West Bengal in 1961.

Humayun Kabir opened the galleries to the public on February 8, 1963. I recall that Barun De was a trustee and Asish Chakrabarty was its first curator.

The museum needed a great deal of attention and funding and was thus handed over to the Gurusaday Dutt Folk Art Society in 1984 with financial support promised by the Union Ministry of Textiles.

Q. How have things come to such a sorry pass today?

According to the museum, there was an “Agreement” signed on 23 May 1984 between the President of India and the Bengal Bratachari Society whereby the centre would “give all financial requirements to upkeep and maintain the Museum”.

The grant was released through the Ministry of Textiles, Office of the Development Commissioner (Handicrafts), National Handicrafts & Handloom Museum between 1984-85 and 1991-92.

Thereafter, the grants were released directly from the Development Commissioner (Handicrafts), Office of the Development Commissioner (Handicrafts), Union Ministry of Textiles. Suddenly, in November 2017, the government sent a letter revoking the agreement and left things in a limbo.

Q. Is there a plan of action to prevent its closure?

There are several attempts to get to people in the centre to persuade it to change its mind. There is also a Facebook campaign and a signature campaign that I am aware of. One can only hope that good sense will prevail because it is possible to make the museum a self-funding body given the right kind of leadership.

Q. Can the library and space be leveraged?

The museum has a fine library on archaeology, folklore and folk art and crafts and research scholars do come regularly to study here but the Crafts Council of West Bengal made excellent use of it by bringing in gifted ladies keen to understand and learn the kantha-making craft to sit and practice here in front of the excellent collection.

This happened for days on end… I would load them in a car and they would spend the whole day here. Some of them are masters today and make me feel that the effort was well worth the while. I suppose the entire property could be used for creative causes that would fund it as well.

Q. What are your favourite pieces here?

I have a great many favourites because Gurusaday had picked out extraordinary pieces from ‘aamshottor’ (mango pulp) chhanch (moulds) to mishtir chhanch (moulds for making sweets). The former were collected from people’s homes and the latter from sweet shops.

The musical instruments are a treat as are some sculptures. There is a striking one of a woman in labour. However, my favourite section is the kantha collection and the favourite piece is the Manada Sundari. This remarkable craftswoman produced this masterpiece that is identical on both sides, replete with innumerable motifs and the tree of life in four corners.

There are also so many kinds of pata chitras, the chouko pot and the jawrano pot and each piece is extraordinary. There is so much to seek, explore and learn from here because this place encapsulates the very best of Bengal’s creative heritage; it is compact and welcoming. I cannot imagine that all this will be lost.

Advertisement