The shy and apparently sombre-looking octogenarian Asok Das now enjoys every single moment of his life in his small and beautiful home in Shantiniketan with his wife, Shyamali, an expert in Mughal art.

The 87-year-old Asok Das is a doyen of India’s art history. In his beautifully sunlit room, he goes back to his innumerable memories, which span his days in Calcutta’s Indian Museum to London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. His contributions as a scholar to various projects to preserve the peerless legacy of India’s mediaeval art forms are extremely noteworthy.

Advertisement

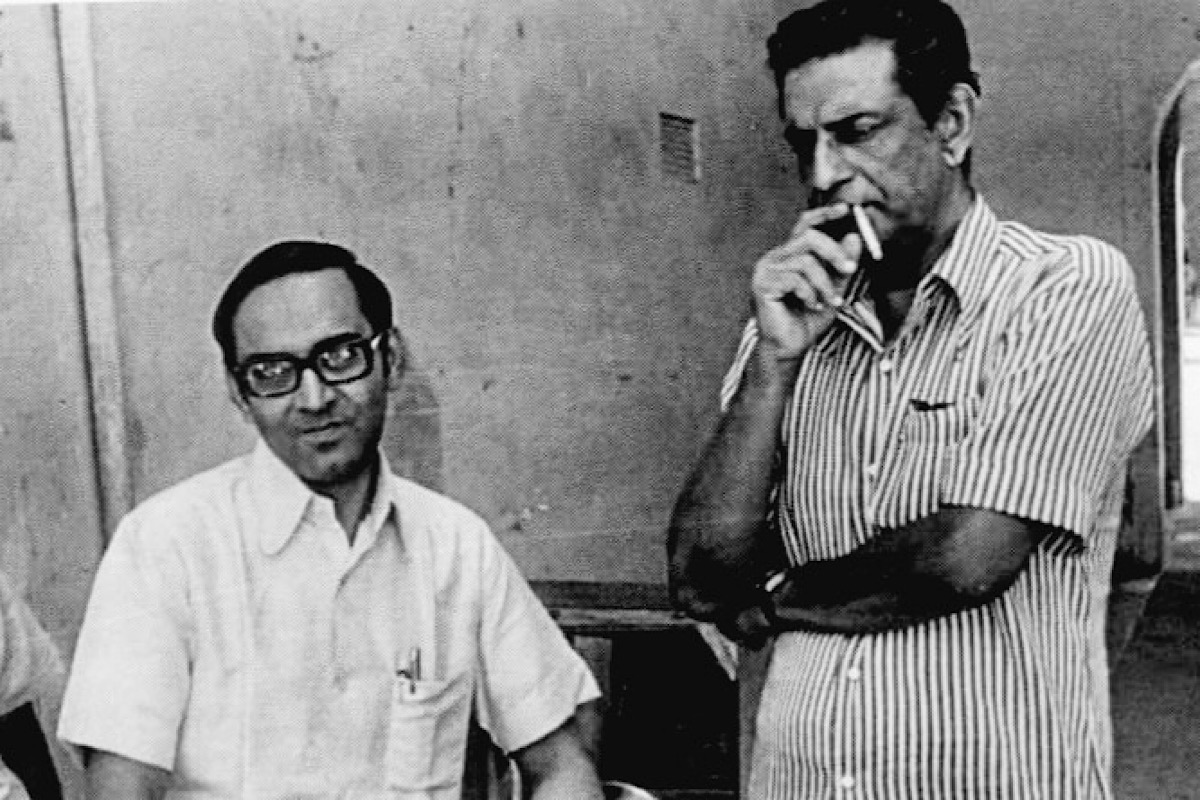

But what the couple fondly remembers is their association with Satyajit Ray. The tall man with his baritone voice and unmatched personality floored them upon arriving in Jaipur in June 1977 to visit the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh Museum and do research for his first Hindi film, Shatranj ke Khilari. After sweeping several film awards since 1955, Ray, who directed Bengali films, decided to make a Hindi-Urdu movie in 1977, produced by none other than Suresh Jindal. It was the biggest news in the Indian film industry at the time.

Advertisement

Asok Das remembers, “I had seen Ray many years ago at an event in Calcutta’s when he was bestowed with the honour of Star of Yugoslavia. Even before that, in 1961, I contributed an article in Sandesh, the magazine he used to edit, but all these were not good enough to build a friendship for a lifetime.”

For him, life took a twist in June 1977 when he received a phone call from Calcutta and heard a baritone voice introducing himself as “My name is Satyajit Ray,” which went on to enquire about the availability of various historical relics and artefacts of the Raj era available from the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh Museum of Jaipur, of which Dr Asok Das was then the chief curator.

“Ray explained to me that he wanted to shoot a sequence showing the movement of the East India Company’s army from Kanpur to Lucknow in 1856 for his next film,” says the man, whose academic knowledge about each and every artefact in the Jaipur museum was unmatched at that point in time. Ray had done his research well.

Ray told him that though the sequence had Uttar Pradesh as his background, he wanted to shoot in Jaipur only for various authentic items and for the easy supply of animals like elephants, horses, camels, etc. It was a pure case of logistics and Ray’s greed for perfection in a periodic film that he was about to direct.

With special support received from Maharani Gayatri Devi, Prince Bhawani Singh and Mohan Mukherjee, then the chief secretary of the Government of Rajasthan, almost every single historical item demanded by Ray was issued from MSMM for the film’s shooting, and Dr Das was responsible for its safe return.

Even after so many years, Dr Das recalls Ray’s extraordinary command on the subject and the exact requirements for such a periodic movie.

“Before coming to Jaipur in a museum at Lucknow, Ray first found a 120-year-old scroll drawing of the army movement of East India Company. For a better idea, he went to the library of London’s India office with the help of MOFA, where he found a better scroll drawn by an unknown artist giving almost all the details of the army movement. He made his own illustration out of that and wanted to picturise the same in Rajasthan with various objects from my museum,” recalls Asok Babu.

Ray finally arrived with his team in Jaipur on 15 June 1977, and “in the next few days, searching various galleries, arsenals, and other collection rooms of our museum, he selected authentic and original samples of muzzle loading guns, camel guns, swords, gun powder boxes, wheeled cannons, etc. He was overjoyed to have Tower London-branded guns that we could provide to him and over satisfied,” says the octogenarian with a broad smile on his face. ”The only regret was that “some of the guns and canons of Nahargarh fort selected by him were not approved for the shooting.”

Ray invited the historian: “Be at the spot on 18 June early morning to see the shooting,” he had said. The shooting spot was Nailathen, a small village near Jaipur. On the day of the shoot, as Dr Das still recalls, Ray was an organised man with superb command over his team, who were managing such huge numbers of people and animals. The shot was simple but very complex to organise. For acting, several British officers and many foreign embassy employees of New Delhi were hired, and Ray, operating the camera by himself, did his work in just one take.

The long line of soldiers in red-white and black uniforms marching with a flying Union Jack, followed by cavalcades, many of them mounted on horses and camels, and their supplies on elephants’ backs, were shot very smoothly.

Asok Das also remembers, “For a sequence that lasted not even 2 minutes on screen, Ray’s dedication to follow every single historical detail was amazing.” During his stay, Ray shot another sequence on the lawn of the Clerk Amer Hotel, and Dr Das was a witness to that as well. It was the surrender of arms by soldiers of Awad to Lord Outram, on the order of Lord Dalhousie.

In 1979, Ray was back in Jaipur and took the help of Asok Das when he shot a very small sequence of Hirak Rajar Deshe.

This resulted in a profound bonding between Asok Das, a doyen in the history of Indian art, and Satyajit Ray, whose interest and wisdom went beyond cinema.

An impressed Ray, who later acknowledged in writing that without the help of Asok, it was not possible for him to shoot that memorable sequence, invited him to contribute to his magazine, Sandesh. He wrote two very important articles: one on the history of Jaipur city and its town planner, Vidhyadhar, and the other on the Jaigarh Fort of Jaipur.

A documentary of Rajasthan’s folk music: The aborted dream

One of the biggest regrets that Asok Das still has is Ray’s decision to abort his project of making a documentary of Rajasthan’s folk music. In 1968, while shooting his first film in Rajasthan’s Jaisalmer, Ray was mesmerised by hearing various kinds of Rajasthani vocal and instrumental music and started to nurse a dream to make a documentary on the subject. By the beginning of 1979, a French television company came forward to produce the documentary, and Ray was highly excited. He started discussing the topic with Asok Das. Unfortunately, the project was called off at the last minute, and Ray got busy with his next feature film.

“This was a great loss to both Indian cinema and music,” says the historian pensively. “When we planned a book on the Farsi Ramayana translated for Akbar from MSMM, I directly requested his cover illustration. He thanked us but could not do it due to other engagements. In 1985, we planned to bring him to Jaipur for an exhibition on photography by Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II, one of the earliest princes to patronise and do photography. The exhibition was named ‘The Photographer Prince’. Due to his poor health, Manik da could not make it.”

Asok Das and Ray continued to exchange letters until 1992, when Ray passed away. As the sun dipped over the western horizon, Asok Das, in his twilight years, remembered the great man and those rich creative days as silence fell all around us.

The writer is a freelance contributor

Advertisement