Radhikka Madan fashion files: 10 looks that had us gasping for air!

Whether it’s experimenting with textures, silhouettes, or color palettes, she continues to set the fashion bar sky-high. Which look is your favorite?

The more predictability that can be built into the circumstances surrounding the writing act, the more one is going to surprise himself with the quality of writing.

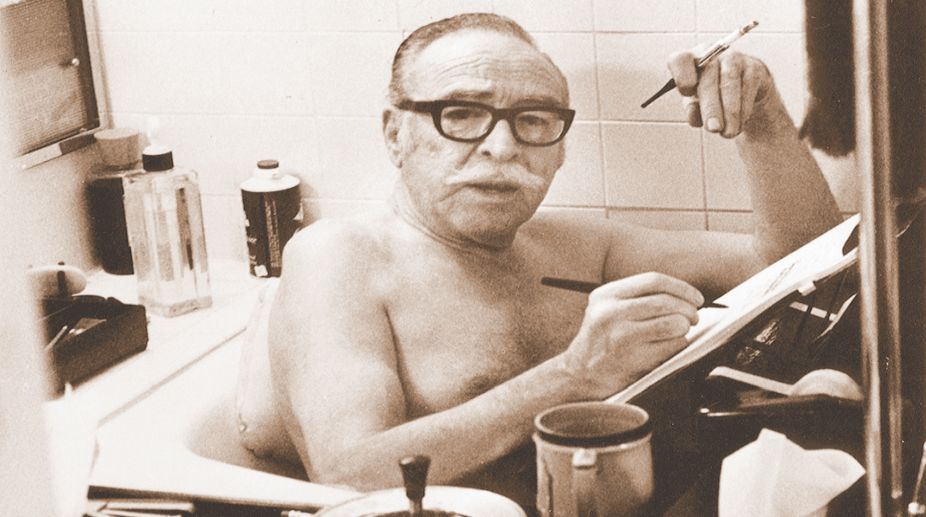

Dalton Trumbo liked to write in the bathtub.

Last month marked the launch of the Smithsonian Institution’s Beyond Bollywood: Indian Americans Shape the Nation travelling exhibit at the Asian American Resource Centre in Austin, Texas, organised by my friends, Archana Vemulapalli, Pooja Sethi and others associated with the South Asian Austin Moms.

The exhibit highlights signal moments in the South Asian American experience, posing a rich counterpoint to the simplistic narrative currently being projected by hyper-nationalist voices about the history and presence of this community in America.

Advertisement

The opening panel was with novelist Chaitali Sen and poet Usha Akella. One audience question that most intrigued me that day, and has stayed with me, concerned writers’ rituals — whether one has them, what they are and what purpose they serve.

Advertisement

While my fellow panellists did not seem too keen on rituals, for me they were crucial 20 years ago and like my attitudes towards everything else in writing — such as ignoring publishers’ needs altogether and writing as though I didn’t expect to get published — I have come full circle about rituals, too.

I joked that day about my bright green shirt, which is in very bad shape — and which I am wearing now, stains and all, as I write this — and about other objects and surroundings I rely on to push me, unthinkingly, into a concentrated frame of mind.

I cannot function, as perhaps others can, in noise and stimulation. For me, the ideal is pure emptiness, a mental and physical vacuum that frees the mind and body to concentrate on the task at hand.

The more predictability that can be built into the circumstances surrounding the writing act, the more the writer is going to surprise himself with the quality of writing.

To be a writer, one must negate everything that might constitute a “writer’s personality”. At the panel I mentioned as the paradigmatic example William Shakespeare, who does not exist for us as a person, because his writing takes up all the space in our imagination.

But what role do rituals play in this conception of the writer’s task? The writer, as I suggested at the panel, ideally shouldn’t function in the time-space continuum we know familiarly, what we mistakenly interpret as “reality.”

Rituals are one — though certainly not the only — way to recalibrate reality in the writer’s favour, so that one is free to imagine in a pure vacuum.

A ritual — such as clocking in at a certain specified hour (for me, it is first thing in the morning before the distractions of the day, as I suspect is true for many other writers as well) or wearing certain clothes or eating certain foods or surrounding oneself with certain objects — triggers a fall into the writing mood, as though by hypnosis or auto-suggestion, like Alice falling down the rabbit hole. But more than that, writers’ rituals are a rude thumbing of the nose at the rituals “normal people” follow in the ordinary conduct of life.

For, make no mistake about it, though writers and artists may be maligned for their eccentric behaviour, the ceremonials of any person dedicated to slaving for corporate capitalism, or any of the established occupations, appear obsessively repetitious from the first to the last waking moment — when and how one dresses and transports oneself, what one eats and how one exercises, how one speaks and conducts oneself in public, the minute attention paid to the tiniest aspects of one’s children’s lives so that they, too, grow up believing in the indispensability of such protocols for “success”.

Compared to the unending parades of everyone else’s unremarked protocols, a writer’s rituals, by highlighting a few specific ones, almost function as antidotes to the conventional idea of rituals. By following a handful of our own choosing, we try to wrench punctuality, predictability, honour and manners away from those who currently monopolise these ideas.

When we writers follow rituals, we are signalling our allegiance to our own modes of fantasy. Using an ancient typewriter (or Word 2000 on a 10-year-old IBM laptop in my case) or writing in longhand or composing only at a certain time or in a specific room, suggests not only a closing off of conventional erotic possibilities, but an opening up of the far greater erotic potential of the imagination.

Objects are everything. Every single object in nature speaks and has moods, including rocks, which look like the most inanimate things of all. But rocks, too, think and feel, as do all objects of fetish, except that writers don’t fix them within the political economy of consuming and using up, but granting them honour as independent entities.

Our sense of independence is defined by the uniqueness of the rituals we follow. To look at a writer’s rituals is to get a glimpse into what he or she considers indispensable for the imagination to take off.

Rituals make us strip down to our barest essentials — that one piece of totemic clothing or object on the desk, or a certain tree one likes to look at, or a cat who is an indispensable companion. Rituals let us compress the entire world to the sanctity of that one object or hour or place, letting us ignore all the rest of it.

It is not so much a method of compartmentalisation, the way popular psychology has it, but a splitting off of different worlds. Once this splitting off has been set in motion, the writer, ritual-bound and honour-obsessed, observes things from a great distance, as though he or she were not even alive.

So rituals are more than eccentric observances, coincidental to the act of writing. At least, that is how I see them. They hint toward an elusive magic, of non-being, of living in the absent present that writers are always trying to seize upon. They are trivial acts of desperation, as though to cling permanently to something that doesn’t even exist.

Although the world may think of them as mere superstitions, I think of them as rather more meaningful. They are enlivened dreams, shortcuts to dreaming while being awake, talismanic triggers to the unknown world.

The writer is a novelist, poet and critic, and author of Literary Writing in the 21st Century: Conversations

Dawn/ann

Advertisement