‘Vicky Donor’ re-release: Ayushmann’s breakout hit comes back on THIS date

Released back in 2012, the film explored the taboo topic of sperm donation in a way that was bold, hilarious, and deeply heartfelt.

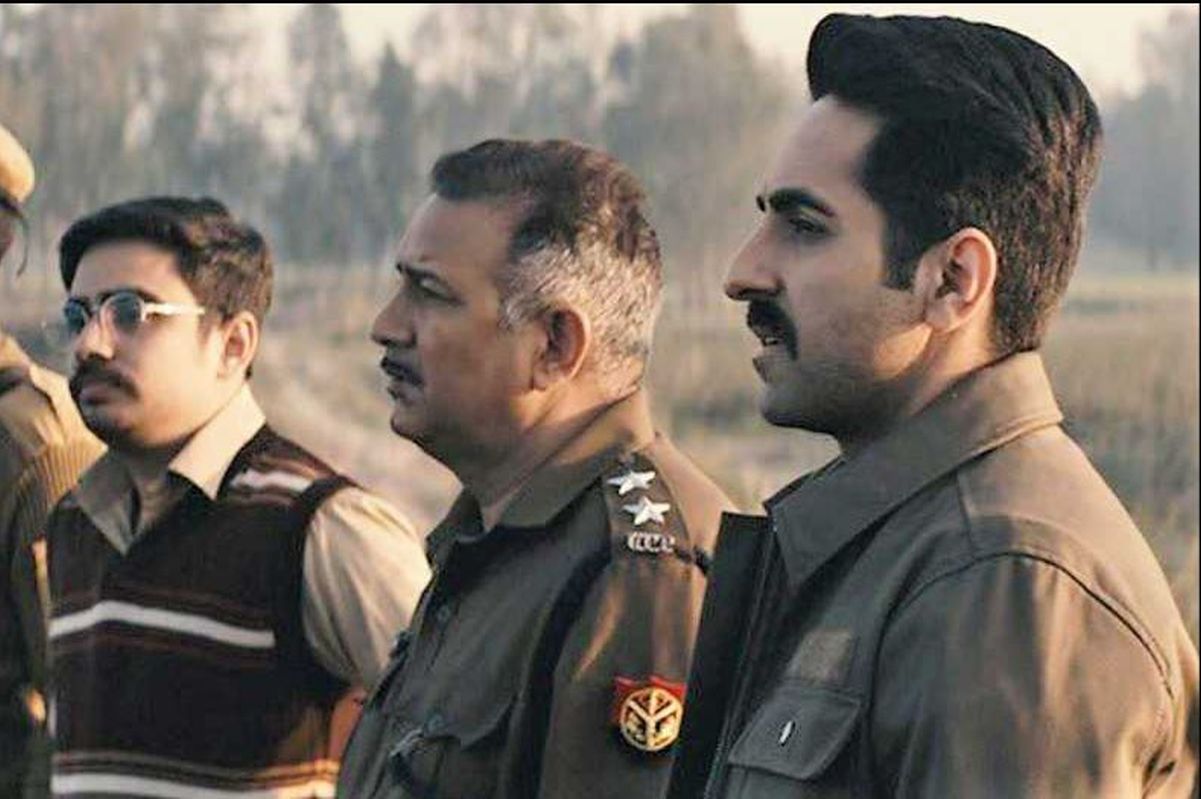

Ayushmann’s character, though new-school, has the Hindi film hero vibe stamped all over him, especially the modern Dev Anand-style slick hair look and the mustache (Neeraj Pandey’s contribution to serious action flicks starring Akshay Kumar).

Amandeep Narang | New Delhi | June 28, 2019 6:46 pm

( Photo: IMDb)

Film: Article 15

Director: Anubhav Sinha

Advertisement

Cast: Ayushmann Khurrana, Isha Talwar, Sayani Gupta, Kumud Mishra, Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub, Manoj Pahwa

Advertisement

Rating: 3

The setting is Lal Gaon, Harimanpur where Ayushmann Khurrana is a posted IPS officer. The opening sequence of the film does one striking thing; apart from just introducing the narrative, it lends two different colour palettes to the setting. Ayushmann Khurrana’s part is shown in shades of brown, mustard, black, grey and blue. The setting with Isha Talwar has bright sunny days and is also imbued with vibrant colours.

Until the later part of the film when she joins Ayushmann, the colour palette becomes one, also suggesting that the narratorial distance that had been there in the first place has been completely dissolved. The fight has now become personal.

In the initial part, the colour palette suggested the difference as Ayushmann says that this (setting of the village) feels like an 80’s film. The difference in the time zones and space through colour, suggested and established a lot of things, apart from the intellectual sensibilities, also the difference in ideologies of the urban and the rural, us and them.

Article 15 is inspired by the Badaon gang rape case where two young girls were found hanging from a tree. In the film, there are three Dalit girls who are gangraped and two of them are killed while one runs away. Through a police procedural set up, the film tries to explore caste-based violence and the larger ideological prejudices associated with it in the rural UP.

In Ayushmann Khurrana’s search for the real culprits and delivery of justice, the film brought in and tried to address too many issues. Despite that, the layers did not feel forced or added, all happened as a consequence of one another, very natural though not subtle.

The drama and the crux are revealed in the first fifteen minutes of the film, heightened and established by the way music, colour and cinematography are used. What keeps the audiences hooked is as to how will justice prevail and the mystery surrounding the case that gets complex and problematic in the second half.

The dialogue of the film is commendable at some places while in some, it felt like translation from English. There are puns on online activism, indirect political commentary, metaphors, poetry and some understated comments that play with the tension of scenes they are used in.

Dialogue is one of the many features and devices of the film that remind one of this year’s Abhishek Chaubey’s Sonchiriya. Both films have a lot of depth, too many ideological clashes, and most of all, existential dilemma explored in varying degrees in multiple characters.

Kumud Mishra and Manoj Pahwa deserve a special mention. Both play cops, though on the caste ladder, Mishra is a Dalit from the Chamar sub caste while Pahwa, is a Kshatriya.

The cop-duo is a Sutradhar figure device that has developed from Vishal Bhardwaj’s Maqbool to Chaubey’s Sonchiriya. In Article 15, the duo ( have come a long way from there) instead of sticking through thick and thin like in other films , here, one participates in the questioning of the social order while the other does so to maintain the ‘santulan’ ( balance).

Just like Ayushmann Khuraana says towards the end of the film, “Haan ya Na ki probability 50-50 hoti hai, aur han bolne wale bohot hai…”, the ‘Na’ is epitomized by Kumud, a dalit policeman and ‘Han’ by Manoj Pahwa.

Manoj Pahwa, by far, has most usually been seen in comedy roles. The figure of a man who feeds dogs, treats them better than humans with a name as ironical as Brahmadutt is played really well by the actor. He is the arbiter of ‘santulan’ of caste system in the small village where the entire film unfolds and goes to great lengths to keep the order in place. Despite having no emotional depth as a character, he delivers lines that are ‘universally acknowledged truths’ and performs in a way that is refreshing. It is only until the latter part of the film that it is revealed he is an equal participant in the crime, and the battle is not just about caste exploitation but also about seamless power abuse.

Kumud Mishra plays a cop called Jatav whose struggle against the system has been a rebellion of a kind where merit wins over favour. In the film, we are repeatedly told, his father worked as a janitor in a local school and Jatav worked his way up the ladder to come at par with others – economically and socially. But as he becomes part of the system he dissociates himself from his caste – calling ‘them’ repeatedly ‘ye log’, ‘inka toh chalta rehta hai’ etc etc.

If the film raises questions on the white-supremacy-complex personified in the figure of upper caste Brahmin, Ayushmann Khurrana, who belongs to the system and poses as a savior figure; it also tries to address questions of a Dalit cop who is psychologically marred and yet has an innocence of a kind that keeps him from trying to explore the larger social, existential corruption of the world around him.

Another interesting feature of the film is how the resistance against social order and establishment is shown. The film personifies all phases of dissent; through violence, non-violence and mediation. As ways of rebelling are personified through different characters on the caste ladder, those who shine most are Kumud Mishra, Ayushmann Khurrana in varying parts, and Mohammad Zeeshan Ayyub.

Ayushmann’s character, though new-school, has the Hindi film hero vibe stamped all over him, especially the modern Dev Anand-style slick hair look and the mustache (Neeraj Pandey’s contribution to serious action flicks starring Akshay Kumar).

His performance shines in some areas, as does in the part where it is revealed to him that two of his fellow-workers are also____ or where he looks at the breakdown of Sayani Gupta and Kumud Mishra when Zeeshan Ayyub _____.

Ayushmann, though is a generous actor and lets his co-stars shine in various scenes. Perhaps, seeing him in a serious role like this, a new thing, makes it a little difficult to dissociate his personality with the role he has been playing, although he tries his best. On the scale of nonconformity he represents the one of mediation, of an enlightened individual of the system that tries to change it by being a part of it.

Zeeshan Ayyub is the poet-narrator of the film, who is a Dalit genius, a fire-brand fighter fighting for the cause of a community he was accidentally born to. His character could have been more worked upon in terms of screen space; a struggle from him and his Robin Hood gang could have taken the film to another angle, had that option been explored.

Let alone that part, he performs well and his poetic narration and humanizing of a fighter who never had five minutes of his life to watch the stars or swing his legs in the river with the love of his life, remind one of Kay Kay Menon from Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi.

In fact, the Gaura (Sayani Gupta) and Nishad ( Zeeshan Ayyub) angle reminds one of the iconic pair Geeta (Chitrangada Singh) and Siddharth (Kay Kay Menon) from Sudhir Mishra’s film.

The difference in both films is that in Article 15, the revolt is coming from that section of the society that is affected by it — a sub culture that explodes throughout the film with the gang of Dalit rebels going on strikes and rallies to establish that they do not support the state and the religious nexus espoused by the local neta — while in Sudhir Mishra’s Hazaaron Khwaishein the educated, urban people moved base during the Emergency in 1970’s to protest for the cause of the oppressed.

Even the encounter scene is classic and reminded of the Rang De Basanti shootout. “Mucho Ko Tau’ Aamir Khan style, and the Bhagat Singh reference was definitive but the backstory of the real hero -savior figure through why-he- began-his-guerilla warfare narration, was one of the best moments of the film.

Sayani Gupta played a courageous Dalit woman whose sister is missing and goes to extreme length to save her and bring justice to her community. Her relationship arch with Nishad could have been explored.

The rugged look for a Dalit, or any person for that matter from the lower classes, can now be changed. The stereotype has been established and a category, also marked. The costumes of the film was otherwise to the point, hero was always best dressed, ‘blue gamcha’ reference on Ayyub’s clothing stood out and suggested the literal and metaphorical weight of the resistance that he carried on his shoulders. And the rest of the cast in the clothing assigned to them fit in the set up of the landscape.

Ideological apparatus’ and dichotomies surrounding the caste system are also explored in varying degrees in the film.

“Agar sab barabar ho jayenge toh raja kaun banega” , “ lekin raja banana kyun hai” – this Brahmanical slate of ideology is questioned and asserted, but only as a passable mention. There is no talk around it; there is show around the same. In that regard, the show and tell does achieve some sort of balance in the film; that which is shown is also told in parts to establish the impact of the action.

When Article 15 of the Indian Constitution is shown in its entirety through a new rendition of “Vande Mataram”, and the film closes for an interval it is a reminder that the social realism of 70s parallel cinema is back if only for a moment.

Despite the gruesome crime and the state of affairs in the heartland, the film never moves towards utter nihilism or pessimism that nothing will change. Despite everything, there is always hope that the social order will and should change for good. Existentialist references, then that are dropped here and there, are finally overtaken by the reality of hope, through an ending of catharsis and relief.

The music of the film is of another genre; murder and mystery are part of the plot of the film but the use of music most commonly used for horror films was out of place at times. The audience is aligned for the cause of justice, but the horror music, if one were to say so, did not fit, though it did keep us on the edge always.

The film is beautiful with the way it’s been shot. Heightened tension and drama in monotone shades go well with the setting of the film. So does colour blue and smoke that almost always precede the announcement of death.

The camera does not really invest in close-ups except in exceptional moments where the tension of the face is required to reveal all, which too are very few and always at the mid-shot level. Thankfully, the camera always follows Ayushmann Khurrana from a distance never staging a set up so that he looked too emotionally vested or prejudiced towards any party.

Another commendable mention in the film is that the hero has no personal battle, or a back-story of a kind that sees him fighting his demons. There is the outsider, educated, urban narrative obviously but never a kind, that justice needs validation from his own personal struggle or understanding.

The film in this regard also does not use Ayushmann as an authorial intervention or narrator which could have made the story’s narration more heroic and personalized. The use of phone conversations between two outsiders, Aditi and Ayan Ranjan (Isha Talwar and Ayushmann Khurrana) to comment and narrate the sequencing of the film kept it outside their domain and yet allowed them to touch and observe it.

Ayushmann does not try to fit in, he observes and performs in a distanced way, so as to do his job and never over-dramatize it.

There is power exploitation too that the film deals with, people in position of higher power will most likely have transfers but those in the middle or at the lower end of the structure will be shot to death. And that is better than facing the court or the political powers; the middle men and those with some power are also grappling with these fears. As did, Nihaal Singh, another culprit who realizes his mistake and atones for it by walking in front of a speeding truck so that his sister does not find out about his crime.

In that regard Article 15 refers to the fact that everyone is a victim of their situations, social background and the baggage they carry from it. The redemption will come only if you are a ‘self-realized’ soul like Nishad, Ayan and Jatav.

There is also a lot of meta-referencing in the film. The bus sequence will remind audiences of the Nirbhaya gang rape case, which is also mentioned in the film. A mention of the Punjabi revolutionary poet of the 70’s, Pash, in Nishad’s poetic renditions, and Bhim Rao Ambedkar’s work and ideological stance also find reference.

The catharsis, achieved with the ending, after that ride of the film for a mainstream movie is a debatable question. If cinema’s primary motive is to entertain, then the end was suitable so as to have the film going in theatres and if it is much beyond that, an alternative ending could have been chosen. But that is not for me to decide. Discretion on this part by the filmmaker for whatever reasons, balanced the film to a large extent.

Advertisement

Released back in 2012, the film explored the taboo topic of sperm donation in a way that was bold, hilarious, and deeply heartfelt.

As Tahira Kashyap once again gets ready to brave breast cancer, she notes how Bollywood music is deeply intertwined with hospitals.

Actor Ayushmann Khurrana has teamed up with Mumbai Police for their latest cybersecurity initiative to raise awareness about the rising threat of cybercrime.

Advertisement