Balmiki Pratibha takes the final bow with its 100th act

On Sunday, 17 November, Rabindra Sadan witnessed the 100th and final staging of Balmiki Pratibha, Rabindranath Tagore’s timeless tale of redemption.

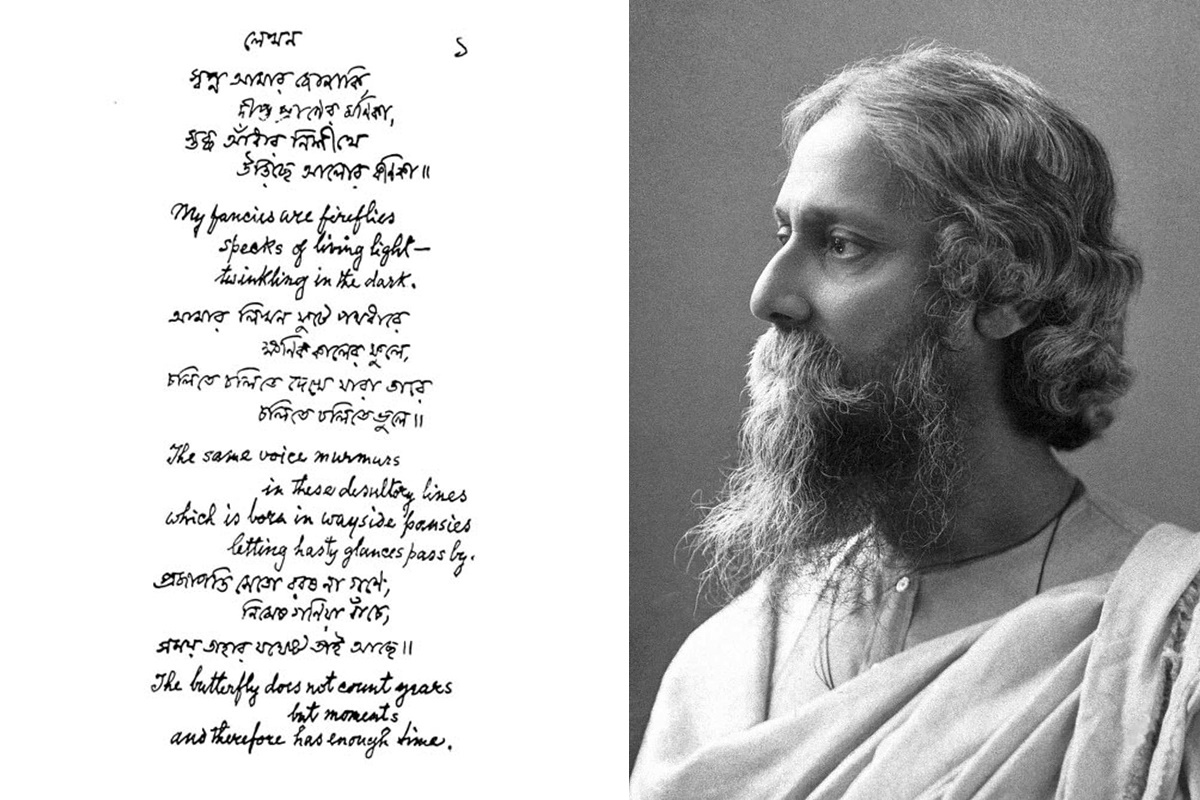

Rabindranath Tagore created special talas or taals — musical meters or rhythm patterns — to suit the specific poetic meters of his verses

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

That Rabindranath Tagore was a multi-faceted personality is known to all. Besides being a poet who was revered by the entire world, he was an author, a playwright, a novelist, an essayist and also an artist too. Tagore acted in plays, was actively involved in the making of some films during his time, and was a music composer too. And he did not stop at writing poems and setting them to tune, he even created specific talas or taals — musical meters or rhythm patterns — to suit his verses. These are known as Rabindrik Taal.

Indian music has a repertoire of talas or taals, a set of rhythmic beats that measure the time each note is allotted in a song. The notation of every song is woven following the set beats of a particular taal. Rabindranath Tagore too had followed taals while composing his over 2000 songs. However, while he used the conventional talas for most of his songs, he felt the need to create new talas for the rest. And we call these rhythm patterns Rabindrik Taal.

Advertisement

Rabindrik Taals follow some non-conventional patterns, which he created to match the meter of his verses. Prominent among them are Ardha Jhap, Jhampak, Sasthi, Ulto Sasthi, Rupakra, Nabataal, Ekadoshi and Nabapancha. There are also some patterns that have remained unnamed.

Advertisement

Traditionally, taals consist of meters with divisions — each starting with a taali (beats that are highly emphasised) or khaali (beat that is not very emphasised). A specialty of Rabindrik Taals is that they are all without a khaali.

It is said Tagore’s inclination towards new rhythm patterns, shorter and lighter, started at a later age.

Here is a closer look at some of the talas Rabindranath Tagore created to suit the specific poetic meters of some of his songs.

Jhampak

Set in five (3|2) matras or beats with two divisions — the first with three beats and the second with two — Jhampak is derived from the conventional Jhaptaal comprising 10 matras in Hindustani Classical music. The Jhampak tempo is generally moderate to slow.

Ardha Jhap

Ardha Jhap has striking resemblance to the first half of the traditional Jhaptaal that follows a meter of 2|3, 2|3.

Sasthi

Sasthi, as the name suggests, carries 6 matras. However, it’s different from the traditional six-beat Dadra taal. Unlike Dadra, which has the six matras uniformly distributed across the two divisions of three beats each, Sasthi follows a rhythm pattern of 2|4. The Tagore songs set to Sasthi taal are usually of moderate pace.

Like Jhampak and Ardha Jhap, Sasthi too has a mirror image tala. Ulto (opposite) Sasthi follows the pattern of 4|2.

Rupakra

Set to eight beats, Rupakra is not uniform in distribution across its three divisions. It follows a pattern on 3|2|3, and finds resemblance to Sartaal used in Carnatic music.

Nabatal

The rhythm pattern of Nabatal has nine beats. While the original is distributed across a single division, it has many variants too. While one variant follows the pattern of 3|2|2|2, another follows 3|6. The other patterns are 5|4, 6|3 and 3|3|3.

Nabapancha

Nabapancha is a rhythm pattern consisting of 18 matras distributed, not uniformly, across five divisions. Moderately paced, the tala follows the pattern of 2|4|4|4|4.

Advertisement