‘L2: Empuraan’ teaser: Mohanlal’s power-packed return ignites massive hype!

'L2: Empuraan' is the highly anticipated sequel to 'Lucifer', continuing the saga of power, politics, and betrayal with Mohanlal’s explosive return in dual roles.

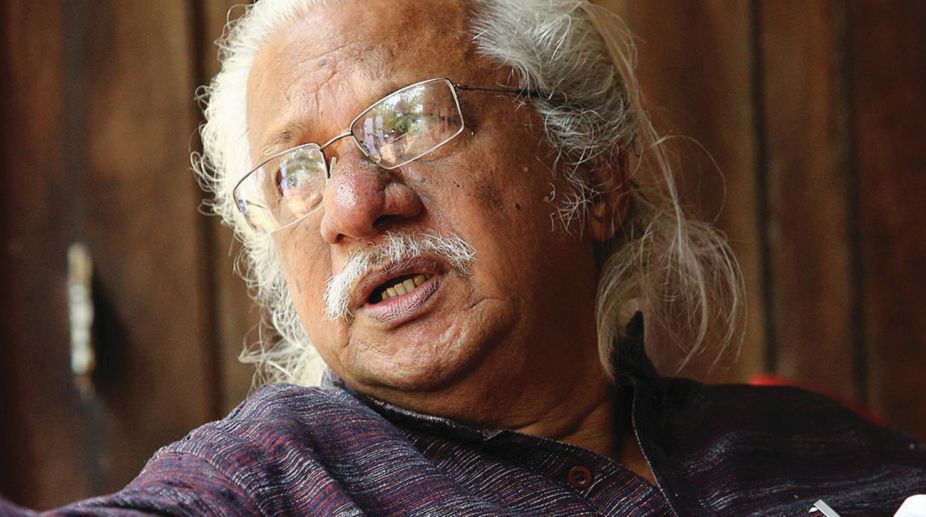

Adoor Gopalakrishnan

It has been more than 45 years since Adoor Gopalakrishnan appeared on the scene with his brand of alternative cinema that took him to festivals round the world. That may not have fetched him the success more prolific directors can claim in the Malayalam cinema.

But if there is one name from Kerala that stands for uncompromising principles of pure cinema, it is this product of the film institute who set the standards for a sustained exploration of the world of the common man. This was reflected in the films selected for a mini retrospective on the occasion of the Kalpanirjhar annual lecture.

Advertisement

It was the tenth lecture in the series and the Kalpanirjhar Foundation couldn’t have chosen a better person to interact with the audience. It was also a homecoming for the filmmaker who had launched the Chitralekha film society in Kerala and had established a bond with his counterparts in Kolkata. T

Advertisement

hat was before the Film Finance Corporation had supported him in his first venture, Swayamvaram, a landmark film that exposes the moral and spiritual crisis of the middle class.

It is the section that has cropped up repeatedly in Adoor’s work. It was not included in the session but the films shown — Nizhalkkuthu, Naalu Pennungal and Pinneyum — reflected his concentration on the social and economic realities in Kerala.

Elippathayam and Kathapurushan are regarded as his most powerful works that used the language of images rather than dialogue to explore the plight of individuals in specific social contexts. The three films selected confirmed the cinematic and human appeal that has been the most enduring aspect of Adoor’s work.

The fact that the lecture was organised by those who have their roots in the film society movement made it comfortable for a filmmaker who has consciously distanced himself from the mainstream. His interaction with the audience at Nandan suggested that he had no regrets about making just about 11 films.

He had confessed at one point that while he appreciated the skills of prolific directors, he himself was never drawn towards films that were “made in the name of entertainment for the masses and designed solely to suit the market”.

He had made fewer films driven by a different agenda — to make audiences more cinema-literate. Even at the level of internal conflicts with which his films are generally concerned, he believes there is enough scope for reaching out to average minds that could eventually develop into perceptive debates.

All this has resulted in the growing popularity of the Kerala international film festival. Adoor is no longer directly associated with the festival that sees a rich harvest of contemporary films from around the world and the presence of international delegates that can rival the arrangements at Goa, which has the support of both the Union government and the Entertainment Society of Goa.

The film festival at Thiruvananthapuram is driven by the enthusiasm of audiences that engage in animated discussions and make the best use of the occasion to enrich themselves. Adoor had provided the impetus in the early days when he spearheaded the work of the Chitralekha film society. The festival remains one of the most favourite destinations of film lovers.

All this has had a positive influence on the Malayalam cinema as a whole. To be sure, there is a popular stream that accounts for the dramatic growth of the industry in the region. But what has really changed the face of Malayalam cinema is the arrival of a new school of filmmakers who have mastered the craft in a manner that has embraced both popular and serious classes.

Malayalam now accounts for a large number of films in all categories and, in quite a few cases, the technical skills that have impressed viewers in other parts of the country. The new trends may not have grown out of the cinematic style that has distinguished Adoor’s work.

It was only natural that the new generation would discover new forms of expression. But what mattered was the creative urge to strike an alternative to mainstream traditions that Adoor had repeatedly emphasised.

What emerged through the latest encounter with one of the leading lights of the New Indian Cinema was the unmistakable humanism that, like the films of Satyajit Ray, had a universal appeal. Nizhalkkuthu speaks of the hangman as a normal human being by cutting across cultural barriers.

Naalu Pennungal strays away from Adoor’s concern with male protagonists for whom women become the strongest source of moral support. Here there are four women drawn from different sections of society in separate stories where the audience finds a common thread in their plight that drives them into a new kind of self-awareness.

Pinneyum has had mixed reactions but sustains the tone and texture that have put Adoor’s work in a class of its own. Seeing a selection of his films and listening to the filmmaker is a rewarding experience in itself.

The question remains how much he can still do in the rapidly changing climate in both his region and the world. In any case, what he has offered in the last 45 years will remain a model of enduring excellence.

Advertisement