BJP MLA Accuses Munde Of Rs 300-Crore Agri Scam And Transfer For Cash Racket

BJP MLA Suresh Dhas also produced a "bribe rate card" which Munde had allegedly charged to give favourable transfers to officials in the Maharashtra Agriculture ministry.

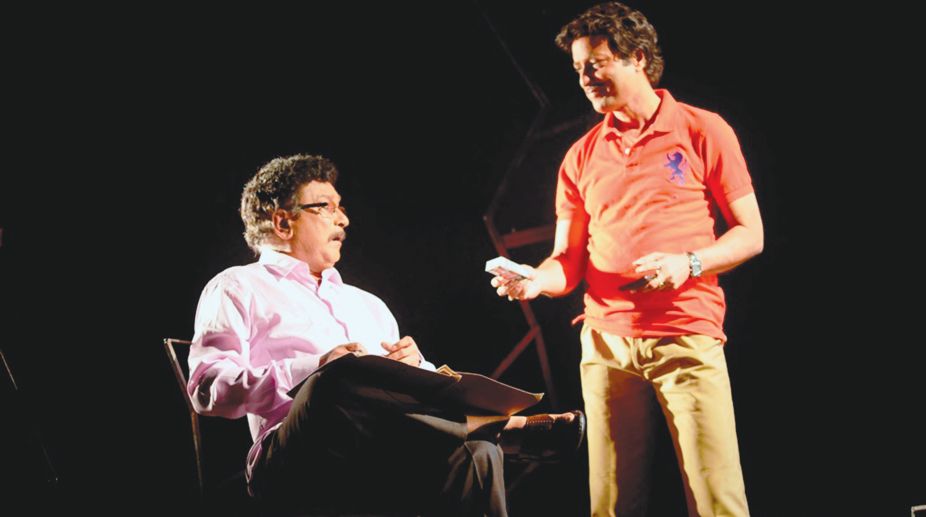

Sayak’s latest play Punoruthhan could not have been better-timed and more contextual in its political and ideological appeal.

The two banks of the river Damodar in West Bengal, spanning Asansol and Ranigunge are spread out over a large area filled with illegal coal mines. The land above the mines is peopled by really poor local Adivasis. But the land beneath defines a different world that promises massive quantities of gold in a metaphorical sense — spun out of the selling of coal and the blood of the miners who die in the pits.

Though in official and legal terms, these mines are the property of the government, it continues to be illegally mined by private and illegal owners known as the khadan maliks with the collusion of the mafia that keeps the exploited labours’ complaints at bay and also the police and the district magistrate who look the other way when their palms are greased. The khadan malik thus, with impunity, violates all safety rules, never mind the loss of life of the poor mining labour.

Advertisement

Sayak’s latest play Punoruthhan based on a novel by Amit Mitra, one of the most outstanding litterateurs in contemporary Bengali literature, could not have been better-timed and more contextual in its political and ideological appeal. Rich in content, it makes very creative use of three deaths of coal miners in an illegal coal-mining spot as the platform and the setting for establishing the endless conflict between honesty and corruption within the police fraternity that is historical in its origins but is escalating at a jet pace in contemporary India.

Advertisement

It also shed light on the discriminations that exist within the police force, the wrongly transfers of honest inspectors to remote areas, death in police custody of an innocent tribal, the oppression of the adivasis and the arrogance and supreme confidence of the bribe taking officers of the police and the government machinery.

The play opens on a coal mine placed imaginatively in the centre of the stage. There is an accident in which three labourers are sucked into the coal pit while working and their dead bodies are not brought up at all. This sets the tone of the play. But this is just the surface of the story which slowly, steadily and very determinedly shifts its focus on the constant exploitation by the powerful of the weak presented in different forms.

Among these are the police force, the khadan owner, and the mafia that threatens the local adivasis. At the other end of the spectrum are the adivasis —poor, unlettered and unprotected against danger of any kind. The adivasi mothers sing their own local songs as they work and march and try to get justice for their dead sons. These two polarities are microcosms of the world beyond these khadans where such exploitation sustains and is encouraged by dishonest administrative forces.

The bodies of these workers are never recovered and their extremely impoverished families are denied both justice from the powers-that-be and compensation from the coal miner who is busy making huge profits by paying the coal miners a pittance. Within this debris of their lives, a voice of protest was once raised by Bharat Kuilya, the young son of the 70-year-old farmer Paban Baran who keeps insisting that his son did not die but will come back, again, maybe in the form of another young man prepared to fight for the downtrodden, the marginalised, oppressed and the tortured.

Kuilya had opened a school for the Adivasi children of Rangamati village under Naw Pahari Police station so that these children could be blessed with education to lead a respectful life in the future and rise against injustice and exploitation. He was the only educated young man among the Adivasis.

He filed a petition through a letter to the home ministry drawing attention to the sudden death of the three coal mine workers which remained out of official records and no compensation was given to the surviving families. Kuilya was arrested on trumped up charges and beaten to death in custody. With the silencing of this radical voice, the Adivasis are stifled. But for how long?

It is a dynamic play that is full of action and dialogue though one wishes that as the action was very well orchestrated and choreographed, the overload of dialogue could have been lessened. The three surviving women — mothers of the three miners who died keep dotting the scenario with their pathos without reducing the scene into tears of melodrama. Theatre is a three-dimensional performance that invites audience participation.

If the performance is ideal, the audience gets absorbed in the play and begins to imbibe the values it projects and propounds. Punorutthan is an example of this participation. The light effects, vacillating constantly between light and brightness with the faded greys in between fit into the volatile mood-swings that characterise the play. Kuilya appears in the first scene spelling out the details of his petition and then disappears while the story unfolds the constant clash between the proud and arrogant additional superintendent of police Anindya Talukdar and the honest officer-in-charge Golok Bihari Kundu over Kuilya’s murder in police custody.

The play is not just about the unfairness of the murder of Kuilya whose peasant and forthright father demands justice but also knows it will never be there. It is also about the conflict between corruption and integrity where corruption always seems to get the upper hand because Talukdar comes from a family lineage of IAS officers and so his action cannot be questioned.

Kundu is a metaphor for honesty. Though he discovers that he is trapped in the murder of Kuilya though he was sent away on another duty and is forced to run away, he comes back. Is he the new Kuilya in a different persona? Will Kuilya rise again from his ashes and raise his voice, collective this time with the Adivasis, be able to get fair justice for the poor and the deprived? Kundu is perhaps, Kuilya resurrected again to raise his voice and force the culprits to surrender. That is what Punarutthan means, right?

The district magistrate Sandip Ghosh’s righteous daughter, Sambita is the sole voice of protest who rises against her own father and demands justice for Kuilya and people of his ilk. This is the only character that strikes a discordant note. But why “discordant?” Can’t the capitalist father’s daughter, studying and living away from her family, have questions about the injustice that defines the world she lives in?

Excellent performances enriched by brilliant production design which makes the stage a fluid space that changes from a coal mine to a village to a small town to Talukdar’s quarters to the jail where Kuilya is kept and then killed, established only through sound effects, music and lighting, makes Punorutthan one of the most powerful performances from Sayak in recent times.

Advertisement