This book describes the swings in Indian policy towards the various contesting factions in Afghanistan between 1979 and 2015, as hard and soft liners in turn gained ascendency in New Delhi. Morality often took second place, since India did not desist from contacts when it served its interest, despite ideological and human rights considerations.

Afghanistan is no easy country to fathom; it has seen the rise and fall of communism, radical Islam and liberal democracy over the last 50 years, and India was inevitably a player there — “Afghanistan is of critical strategic interest for India,” writes Paliwal, the first frontier of the war on terror, and “imagining India without Afghanistan and Afghanistan without India is impossible.”

Advertisement

India needs to have good ties with Kabul irrespective of Afghanistan’s political and economic woes. From 1996 to 2001 when the Taliban were in power, India gave support to the Northern Alliance; from 2001 it concentrated on reconstruction and infrastructure development in that country, and from 2011 it supported an Afghanled reconciliation between all parties.

In the foreground was always the quadrilateral of conflicting interests of the Afghan government, the US, Pakistan and India. India’s main handicap is the lack of geographical contiguity, while Pakistan’s biggest advantage is precisely that —a 2200 km border. Karachi port is landlocked Afghanistan’s lifeline.

All friendships fostered by India in Afghanistan indicate an anti-Pakistan bias, although India maintains “a studious silence …over the legitimacy of the Durand Line” that is bitterly contested between Afghanistan and Pakistan. India will react to any step that gives excessive strategic weight to Pakistan and Pakistan’s efforts to push India out of Afghanistan will only increase India’s determination to deepen its footprint. “Any attempt” writes Paliwal, “to exclude India would be counterproductive if the aim was to stabilise Afghanistan,” and there is abundant goodwill for India in that country.

Yet, the West, anxious to mollify Pakistan, is wary of the Indian presence. Despite this, and what comes as a surprise, is that India often kept its ties with Pakistan in consideration; Foreign Minister Narasimha Rao in 1981 said, “we have an abiding interest, even a vested interest, in the stability of Pakistan,” and Manmohan Singh was anxious to preserve the halting peace process. While India seems to avoid measures that complicate relations with Pakistan, there seems to be no reciprocal sensitivity from Pakistan.

There are immense complications for India in contacting Afghan factions. India keeps in mind three vectors — the balance between Afghanistan and Pakistan to prevent an Afghanistan that is dependent on Pakistan; to support the Afghan state, knowing that whichever international actor plays the biggest role has the greatest leverage, and after 9/11 Afghanistan is dependent on US support, which India has to take note of.

Finally, the degree to which the political factions in Afghanistan themselves wish to engage with India, since it is difficult to have cordial ties with all. In its search for friendships, after the Taliban regime’s fall in 2001, India is engaging widely. Karzai after 2004 was considered a friend, and Abdul Ghani is supported after his outreach to Pakistan failed. There is natural convergence of interest between India and Afghanistan on Baluchistan and Pashtunistan, and on separating the Taliban from Pakistan.

Afghan friends make demands to neutralise their political rivals — the same feature in our other neighbours like Nepal and Bangladesh — but the rub is that if India does not seek alliances, another country, like Pakistan, will step into the breach. India has also to consider the security of Indian residents there, the patronage network and the gross venality which are a fact of life. Despite $2.3 billion in aid, “India remains politically marginalised if not inconsequential,” whereas Pakistan, despite its gross interference, is considered indispensable for bringing peace. Contacts with the Taliban are a debated issue in Delhi since 1980.

The author strongly favours such contacts, and notes that the Taliban were keen on connections with India even when in power, but the Indian Airlines hijack was hardly a good portent. Paliwal writes, “India’s ‘national allergy’ to Muslim fundamentalism seemed misplaced” at a time when even the Kabul government was engaging with Taliban. The Afghan Taliban did not attack India though the Pakistan-based Taliban did, and the Taliban want to engage with India because it gives them credibility in Afghanistan and India is the only counterweight to Pakistan.

There was never a large presence of Afghan militants in Kashmir, and most were private individuals without mujahideen backing. India can never assess to what extent the Taliban were beholden to Pakistan, though the impossibility of defeating such a heterogeneous group like the Taliban makes India think again. Paliwal makes good points here, but given the Taliban’s record of human rights, the debate will continue.

With both the USSR and US, India cautioned against hasty withdrawal that would facilitate Pakistan moving into the driver’s seat. In fact, Vajpayee urged Bush to get involved in Afghanistan to pressurise Pakistan, contrary to Indian traditional policy to keep outsiders out of our region. For its part, Pakistan and its media charge India and Afghanistan of working together to catch Pakistan in a pincer movement and of funding the Afghan-based Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan. India does not mind Pakistan being part of an Afghan-led Afghan-owned peace process, provided it is not the prime mover, and if India and Pakistan ever get to discussing Afghanistan, it would give credibility to bilateral dialogue.

There is a wealth of material in this work, overwhelming at times but essential to those who wish to delve deeply into the problems faced by India, Pakistan and Afghanistan with the turmoil in Afghanistan. The book is more interesting as it draws nearer our contemporary period, with an excellent epilogue. We find repeated references to Indian espionage activity in Sind, Baluchistan and the Pashtun areas, but with no details — Paliwal assumes it exists and leaves it at that. Modi’s implied support to POK, Gilgit and Baluchistan “at a time of high toxicity in Afghan-Pakistan relations” he considers significant.

On the debit side, there are too many repetitions, the customary appalling copy-editing by HarperCollins, and demotic usages that should have been edited out in a serious book. Paliwal misinterprets Indian policy as having an “alleged aim of neutrality” on Swiss lines and “genuine neutrality”, neither of which is correct.

No foreign policy can afford to be static; therefore the author’s critique that there is “no single policy that New Delhi practices towards Afghanistan” is misplaced.

(The reviewer is India’s former foreign secretary)

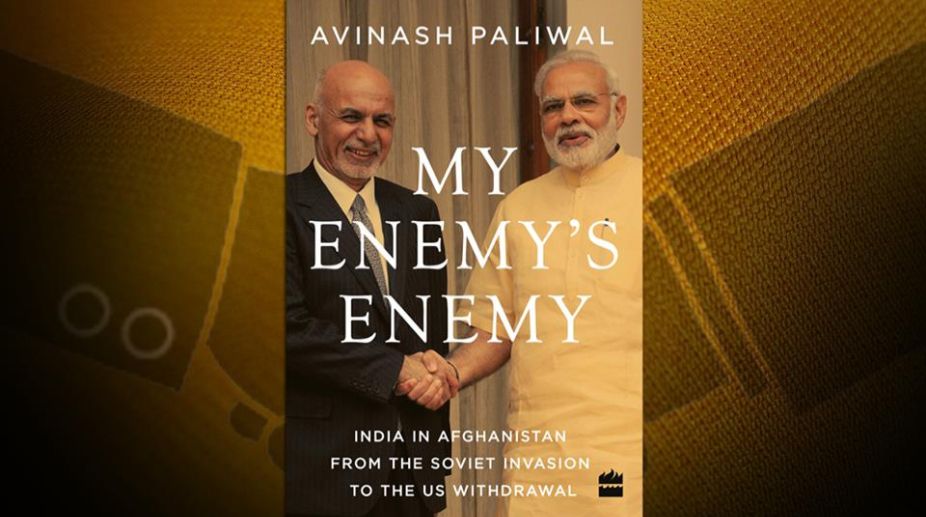

MY ENEMY’S ENEMY

By- Avinash Paliwal Harper Collins, UP India, 2017;

Rs 699