Who was Dr S M Mohnot, renowned primatologist and environmentalist?

Dr S M Mohnot who was World’s renowned Primatologist and Environmentalist Professor passed away yesterday. He died after a prolong…

The vibrant field of culinary literature involving Kolkata’s food history has been further enriched and expanded by this masterpiece… A review.

The Spanish proverb that the belly rules the mind is a solid vindication of the fact that food provides nourishment not only to the body but also the soul. No social, political or economic past of a region is complete without its food history. To go by the words of American economist and environmentalist Winona LaDuke, “Food for us comes from our relatives, whether they have wings, fins or roots. That is how we consider food. Food has a culture. It has a history. It has a story. It has relationships.”

We all need food to survive, but when the element of choice and innovation entered the evolutionary process of food preparation and consumption, penchant for more sumptuous, soul-stirring food varieties in their multiple hues, tastes and flavours began to grow in all societies and climes. Bengalis are traditionally held to be food-loving people. They have forged an inextricable bond with numerous savoury servings of diverse origins over a long period of time. Food is everything — culture, habit, craving and identity.

Advertisement

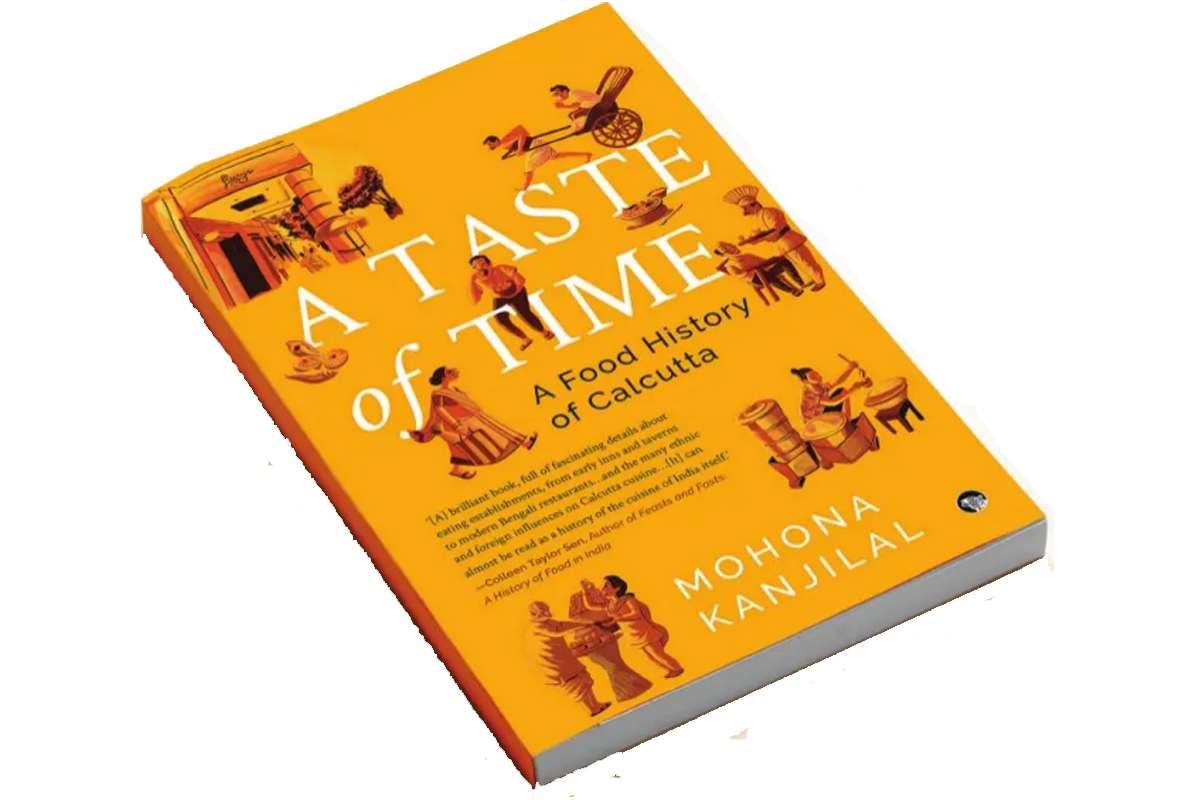

As more communities began to arrive and settle in the City of Joy, Calcutta, or today’s Kolkata, evolved as a melting pot of diverse cultures that also brought in a trail of varied culinary customs and recipes to give a unique dimension to the city’s food profile. Mohona Kanjilal’s extensively researched book, A Taste of Time: A Food History of Calcutta, quite appreciably captures that aspect of Kolkata’s colourful culinary world over the decades. With delectable narration bolstered by facts and pleasant stories, the book is never allowed to be relegated to the level of dry culinary dissertations, cookbooks or food guides found aplenty in the market.

Advertisement

Kanjilal’s maiden venture into the culinary field is a veritable tome of 488 pages with 28 of them devoted to an exhaustive bibliography and a detailed index. It is a culinary tour de force aiming to journey through the different periods of time in search of origin, evolution and tantalising diversity of innumerable food items, ingredients, food habits and hangouts in, around and beyond Kolkata. The author amasses and analyses a great number of pleasant food anecdotes, culture-cuisine interactions and numerous social and political happenings across different periods of history that have a powerful imprint on the colourful culinary tapestry of the city.

A great number of immigrant communities settled in Kolkata and left an indelible mark on its culinary tradition. While many dishes of those expatriate communities have fallen out of favour in course of time, some have lasted, often in modified forms. The Armenian dolma, which required grape leaves and ground meat in Europe, has instead seen the use of cabbage leaves, tomatoes, onions and vegetables like patol or pointed gourd for stuffing, and consequently, gave birth to an item like patoler dolma.

Many exclusive immigrant dishes and delicacies are now a thing of the past in Kolkata, but some have survived the vagaries of time. Armenian lavash bread, Anglo-Indian dak bungalow curry and Jewish alu makallah have faded, but the warm smell of baked breads and cakes from Flurys and Nahoum’s still keeps nostalgia alive.

A host of posh hotels, restaurants and guesthouses are also traced to their antiquity as evolution in the hospitality industry is directly related to the changing culinary culture of a city. Their signature dishes and celebrity clientele are also brought into focus. As one goes through thought-provoking material from one page to another, they realise how complex, diverse and unique Kolkata’s cuisine is, and its long and rambling history, presented as a sumptuous narrative. In exploring the culinary evolution specific to the city across a great variety of cuisines and time periods, the book dexterously dovetails history, stories and recipes, relating to numerous dishes, desserts and drinks. It traverses continents, dynasties and centuries in a time machine to explore the origins of umpteen food varieties or customs of immigrant communities, and how they have formed, adapted or altered the city’s food habits.

Pages devoted to tea, engrossing albeit a bit digressive, take one first to China where the brew originated as a medicinal drink around 1600 BCE and was popularised afterwards as a recreational drink during the Tang dynasty from 618 CE. It then travelled to Europe and from there to India, thanks to the culinary predilections of colonial rulers.

Like fruit juice, tea was also introduced to the Bengali palate by the British. In the early days of tea in Kolkata, British companies like Brooke Bond (founded in 1869) and Lipton (1888), and the Indian firm A Tosh and Sons (founded by Ashutosh Ghosh and his eldest son Prabhash Ghosh in 1897), ventured into the tea business. While Brooke Bond carts would travel around the city and make free tea for the public and aficionados, Tosh capitalised on the “Be Indian, Buy Indian” sentiment and sold their tea as a swadeshi product.

Kanjilal describes elaborately how cha, coffee which arrived later, chops, cutlets and other fried snacks have become an indispensable part of Bengali adda culture, and how food joints serving them became favourite haunts of litterateurs, academicians, freedom fighters, filmmakers, students and the hoi polloi. They engage in intellectual interactions on diverse matters over steaming cups of tea or coffee with heart-warming accompaniments like fish fry, chicken pakora and other crispy or fluffy fritters.

While external influences have played a part in shaping Kolkata’s food culture, a host of Bengal’s very own delicacies and food customs have steadily held their ground. Bengali sweets such as sandesh and rosogolla, and prominent food items like shukto, fish curry, kosha mangho, bhoger khichuri (devotional food offering of lentil and rice), lau chingri, neem begun, telebhaja or fritters, and customs like eating meals by sitting cross-legged on the floor, chewing paan after meals, have remained irreplaceable things in the collective consciousness of Bengalis.

The great metropolis, as a culinary melting pot, has in the same breath included in its platter colonial desserts and confectioneries like puddings, cakes and pastries, Gujarati dhokla, Bihari sattu sherbet, filling food varieties like Awadhi biryani, Chinese hakka noodles, Punjabi dal makhani, Marwari dal baati churma and South Indian dishes like idli, dosa, upma and utthapam. The engrossing stories of some iconic food joints like Bhim Chandra Nag, Kim Ling, Tung Fong, Calcutta Stories, Magnolia and Nizam’s add to the sumptuous array.

Distinguished by noted authors like Minakshie Das Gupta, Bunny Gupta, Jaya Chaliha and Chitrita Banerji, the vibrant field of culinary literature involving Kolkata’s food history has been further enriched and expanded by Kanjilal’s masterpiece. After partaking of the rich and palatable fare purveyed in A Taste of Time through its ringside view of Kolkata’s culinary diversity, relishing food in the city will surely be a happier and tastier experience.

The reviewer is a freelance contributor and teaches English at Sailendra Sircar Vidyalaya, Kolkata.

Advertisement