Special court grants bail to Ayan Sil in Bengal school job case

A special court in Kolkata on Friday granted bail to private promoter Ayan Sil in the cash-for-school job case.

The reviewer is the principal of Women’s Christian College, Kolkata, India.

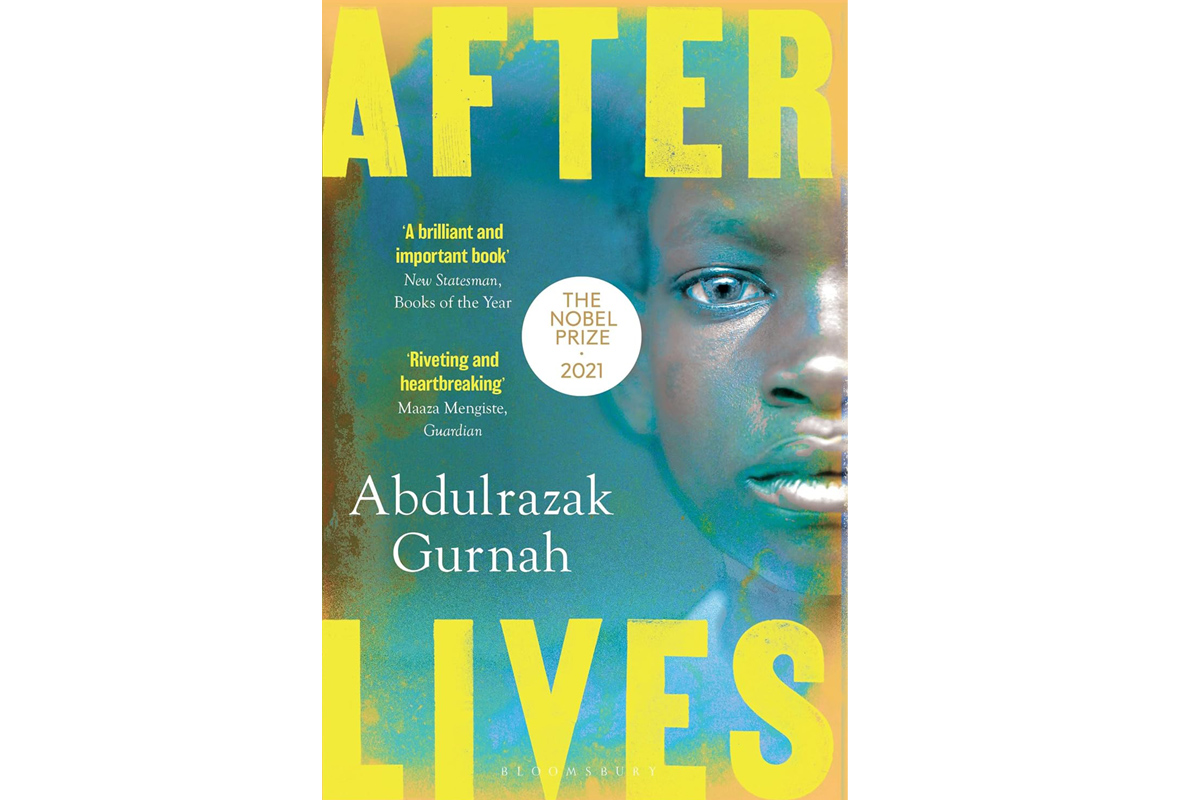

Nobel Prize winning author Abdulrazak Gurnah’s novel Afterlives is a tale told by a master, full of silences and synapses, signifying much. His characters are outliers caught on the underside of things, suspended as they are, in the precarious penumbra of the periphery, being for the most part, subalterns on the sidelines of major historical phenomena such as colonialism, migrations, revolutions and wars.

The novel accomplishes a powerful convergence of several narratives, linked in terms of time, place and relationships. Khalifa, the first protagonist to be introduced, takes in Ilyas’ sister, Afiya who, in turn marries Hamza, these four characters being the focal figures in the novel. Interestingly, each of these four protagonists trails a complex history wrought through centuries of racial, tribal, commercial and cultural intermingling amongst the peoples of the Indian Ocean and East African coasts.

Advertisement

Afterlives is a novel about choices, or the lack thereof; of loss, abandonment and identity; of forced labour, and of great spasms of movement across the globe. Ilyas, for instance, is lost to his family twice. The first time, he is stolen by the German Schutztruppe, (the army of African mercenaries known as askari), though he’s freed subsequently and sent to live on a farm where its owner had him educated at the mission school; and the second time around, he voluntarily joins the same outfit as an askari. Ilyas is never heard from again, and his family learns of his death decades later when Afiya’s son (and Ilyas’ namesake) researches the truth about his uncle’s end in a concentration camp in World War II. Ilyas’ absence, which haunts Afiya throughout her life, enacts the epistemological ellipsis that is at the heart of Gurnah’s storytelling.

Advertisement

Afiya is abandoned twice, first by her father, (“he gave her away,”) and then by her brother. There are characters in the novel who are jettisoned by the system – some stranded in the sands left behind by colonialism; others (like Ilyas) tossed into the faultlines between ideologies and affiliations; and yet others, like the askari released abruptly in the middle of nowhere and left to fend for themselves. The unimaginable hardships endured by the latter, and their casual abandonment by European officers in the event of injury or incapacitation in combat, as also their desertion of the Schutztruppe when they could no longer take it, are all examples of kinds and degrees of abandonment.

While Afiya had been treated like an indentured labourer by the family which had taken her in, Hamza, too, had been practically sold into slavery to a merchant as collateral for his father’s accumulated debts. When Khalifa associated shame with such servitude, saying, “To be bonded to another, to have your body and spirit owned by another human being,” and asking if there was “a greater shame than that?” Hamza demonstrated the nobility and resilience of the human spirit affirming, “The merchant did not own me body and spirit.” Through chinks such as these the light shines through, illuminating the recesses and resources of man’s infinite capacity for suffering and transcendence.

Afterlives is literally about life-changing developments in the lives of its protagonists, and how these contribute to rebirths of the same. It is as though the characters have several lifetimes packed into a single time span, so varied and incredible are their experiences.

The German colonial presence in the part of East Africa known as Deutsch Ostafrika – the repeated rebellions by local groups and different ethnic communities there, the war of attrition between the colonial powers, the defeat of Germany by Britain in World War I, and the introduction of British colonialism in these parts followed by the formation of independent Tanzania out of Tanganyika and Zanzibar constitute, in part, the seething scenarios of this compelling novel with its welter of travels, trades, and traumas.

Africa is a brooding presence in the novel, haunting it like the breezes of the kaskazi drawing stories to its shores; inhabiting it like a riff which resonates with its variations of pain and loss; it is, at the same time, the lingering perfume of the shekhiya as she tries to exorcise what she believes to be a spirit in the boy Ilyas. Africa is also the “grieving woman” who weeps and whispers through a bewildered and “possessed” child; the babel of the bazaars with their bewitching alchemy of accents – Arabic, Persian, Swahili, and Kiswahili, along with a host of other languages; and the primordial drumbeats of the heart.

“You want me to tell you about myself as if I have a complete story but all I have are fragments snagged by troubling gaps, things I would have asked about if I could, moments that ended too soon or were inconclusive,” says Hamza to Afiya when she desires to learn more about his past. This “complete story,” is what Gurnah sets out to tell like all good storytellers, but the fallible narrator of the novel is constrained by a lack of omniscience.

Such gaps are common in Gurnah’s writing; they bear testimony to his aesthetic detachment from his characters, his historical objectivity with regard to their position in the larger unfolding of events, and his methodological honesty in allowing the tale to do the telling rather than assuming a magisterial familiarity with the totality of his fictional representation.

This should not come as a surprise as the reader has been prepared for such ideological inversions through earlier references to some of the African soldiers’ strong sense of affiliation with the European colonisers. The askari were, in fact, so merciless in pursuing their white master’s cause that they “left the land devastated, its people starving and dying in the hundreds of thousands…” They fought for the imperialists with a “blind and murderous embrace of a cause whose origins they did not know and whose ambitions were vain and ultimately intended for their domination.”

An attitude which is inexplicable under the circumstances gains a particular intensity during the Battle of Mahiwa fought between the imperial German and British forces in 1917 in the East African Campaign of World War 1. “At this stage of the war, most of the soldiers involved in combat were Africans and Indians: troops from Nyasaland and Uganda, from Nigeria and the Gold Coast, from the Congo and from India, and on the other side, the African schutztruppe.” The askari, their wives, children and carriers died of blackwater fever, crocodile attacks, malaria, dysentery and exhaustion when they were not killed in battle and yet, there was scarcely any recognition of their extraordinary contribution. The narrator observes ironically, “Later these events would be turned into stories of absurd and nonchalant heroics, a sideshow to the great tragedies in Europe but for those who lived through it, this was a time when their land was soaked in blood and littered with corpses.”

Afterlives is history, drama, political critique and social ethnography in the form of literature written in the most lucid and luminous prose. It shows how cataclysms at the centre of things convulse the margins in far-reaching seismic waves – causing movements that uproot and transplant characters in different quarters of the globe. And through it all, one sees among other tendencies, the quest for survival, and in that context is reminded of William Faulkner’s Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech which attests that “man will not merely endure: he will prevail.”

Advertisement