Indian democracy on its last legs: Prem Shankar Jha asks tough ques in new book

Moravia’s cynical yet supportive take on democracy is akin to Prem Shankar Jha’s latest book “The Dismantling of India's Democracy”.

“One can mull over a story idea every day after it has occurred and yet not write it. The mind keeps going to it and working on it and then one day when one sits down it is ready to become a story. It is only a question of recognising that moment when it can become a story,”

IANS | New Delhi | March 22, 2021 1:04 pm

'Sometimes, stories lie dormant in the mind for years'.

An idea, an experience or even a fleeting moment can become a story. But the story does not get written immediately after you think of it. Sometimes the story ideas live dormant in the mind for years and then one day become stories, says the multifaceted Dr C.S. Lakshmi.

Lakshmi, an independent researcher and archivist in Women’s Studies for more than 40 years and who, writing under the pseudonym Ambai, has been a significant voice in Tamil literature for the past four decades with her stories about love, relationships, quests and journeys.

Advertisement

“One can mull over a story idea every day after it has occurred and yet not write it. The mind keeps going to it and working on it and then one day when one sits down it is ready to become a story. It is only a question of recognising that moment when it can become a story,” Ambai said in an interview.

Advertisement

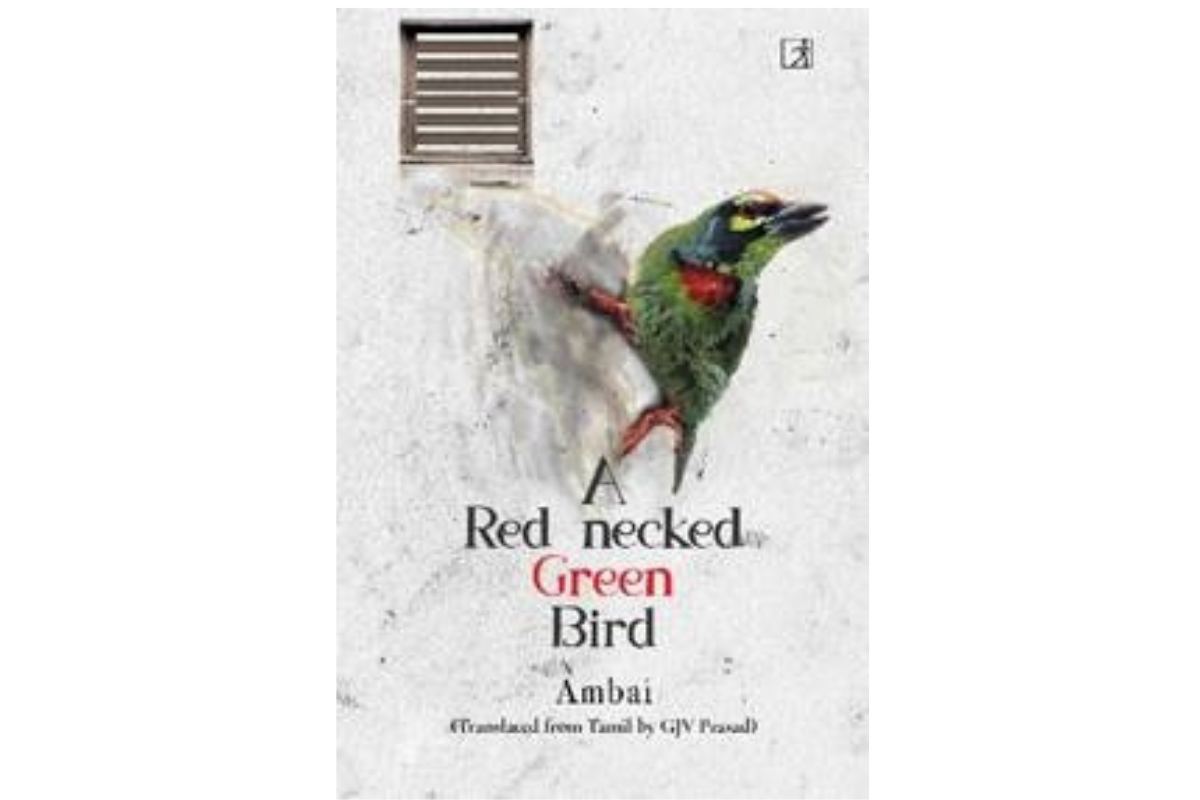

“A Red-necked Green Bird”, her seventh collection of short stories, translated from Tamil by G.J.V. Prasad, a former Professor of English at JNU, has just been published by Simon & Schuster.

Myths and legends jostle with the contemporary in these stories where social issues of our times resonate with the inevitability of the past.

The lyricism of Carnatic ragas permeate the pages of this quiet and powerful book in which love is rendered in all its immeasurable avatars – parental, carnal, platonic, romantic, divine. There is the woman who reinvents the notion of love in a unique way that amalgamates technology and spirituality through the internet; a man full of love who can sing Bulleh Shah and the woman who has lost her all in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots; the woman in the title story who stands by her deaf daughter but understands why her husband must leave the home they have built with love all these years; the man who finds out what it is to be a woman after a dip in the pond. These are stories shorn of sentimentality but have a deep understanding of what it means to live, to love and to die.

How did she come to adopt the short story format?

“That is the only format that worked for me. When I was young I tried writing poetry but they were really bad poems! I have kept them for myself. Even now occasionally I may write something like a poem but I know it is it is not a poem. I wrote an adventure novel for children when I was 16 and another �adult’ novel when I was about 19. Both of them won prizes. The adventure novel is fine considering I was only 16. But the other one on platonic love is a very immature novel written when I knew nothing about either love or the body. Since then the novel format has not worked for me. I enjoy writing short stories and I find the short story format quite challenging,” Ambai explained.

To that extent, her writing blends seamlessly with her work in the sphere of Women’s Studies over the past 40 years. How has the scenario evolved, what are the deficiencies that remain and how can they be resolved?

“I have done work on Tamil women writers and their writing and have also done work on women musicians, dancers and painters. The work done on writers, musicians and dancers has come out as books. Women’s Studies came out of the women’s movement and it took time for it to evolve as a discipline and get due recognition.

“It is an interdisciplinary area of studies and a lot of work has been done and a lot remains to be done like in any other discipline. There will always be lacunas in any area of studies which keep getting pointed out and then new studies come up to fill the lacunas. Considering the vast area Women’s Studies covers, I think a lot of good work has been done taking into consideration many different aspects that cover women’s lives in their varied identities and activities and women’s history,” Ambai elaborated.

How does she balance these two activities?

“Whatever activities one takes up they are what one’s life is all about. And don’t remain separate. They have a way of blending into one another. One can’t make out where one ends and the other begins, the borders are very blurred. It is like not knowing where the river ends and the sea begins. One does not really have to make an effort. I do research because I am interested in the human condition with gender as a factor and I write for the same reason,” Ambai maintained.

Her third avatar is as Director of SPARROW. What does this entail?

“This is a very difficult question to be answered briefly. Like someone once asked me to speak about Tamil literature in five minutes! To put it briefly, in SPARROW, which is an acronym for Sound & Picture Archives for Research on Women, we collect oral history and visual material on the life and history of women. We do this in many different formats like books, journals, films, visual material like photographs.

“It is an archives registered as a trust and we feel that archiving is also being actively engaged in bringing about change. We have also made documentaries and published books. We take up many activities like workshops, writers’ meets, photo exhibitions and so on basically because we believe that positive change is possible only when we understand women’s lives, history and struggles for self-respect and human dignity,” Ambai said.

What next? Is she working on a new collection of short stories?

“I am eternally working on a new collection of stories. That is something I will never cease to do I think,” Ambai concluded.

Advertisement

Moravia’s cynical yet supportive take on democracy is akin to Prem Shankar Jha’s latest book “The Dismantling of India's Democracy”.

The stories are rooted in the joys and sorrows of poor villagers as they face nature’s fury or revel in her bounty.

Raids coincided with a CPM protest against central agencies’ delay in ongoing probe

Advertisement