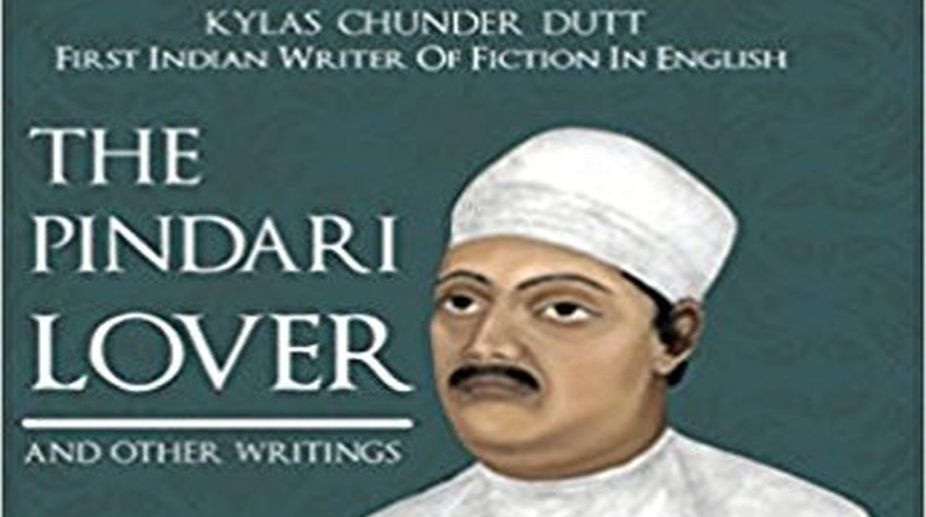

Students of Indian English literature have routinely regarded Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s debut novel, Rajmohan’s Wife, to be the first fictional narrative written in English, in colonial India. Rajmohan’s Wife was serialised in 1864 and published in book-form in 1935. Kalyan Chunder Dutt, the editor and great great grandson of Kylas Chunder Dutt (1817-1859), in his compilation of the literary writings of the distinguished Dutt family informs us that “A Journal of Forty-Eight Hours in the year 1945” was the first published fictional narrative by an Indian.

Son of Russomoy Dutt who was a member of the Managing Committee of Hindu college, the writer Kylas Chunder was then 18 years old and a student of Hindu College. This short fiction was published in The Calcutta Literary Gazette on 6 June 1835 and the editor of the literary magazine was the distinguished litterateur, Captain David Lester Richardson. Within four days of the publication of this futuristic journal, the author was faced with the charge of sedition and the editor accused of serious indiscretion.

Advertisement

So what did the teenager Kylas Chunder write to attract the ire of the formidable East India Company? Of course it would be sheer fancy to think that the journal could have inspired the Sepoy Uprising against the East India Company in 1857. But then this is what 18-year-old Kylas wrote in the very first paragraph of the journal, “The People of India and particularly those of the metropolis had been subject for the last 50 years to every species of subaltern oppression.

The dagger and the bowl were dealt out with a merciless hand, and age, sex or condition could not repress the rage of the British barbarians. These events, together with the recollection of the grievances suffered by their ancestors, roused the dormant spirit of the generally considered timid Indian”. It would not have been surprising if the East India Company had transported the daring Kylas to the Cellular jail branding him a terrorist. Thankfully that abominable prison house was constructed in 1906, long after the death of Kylas Chunder Dutt.

However, not all the fictional writings of Kylas Chunder Dutt were so intense and patriotic. Instead in the romantic short story The Pindari Lover, the purple passages and florid descriptions seem to be a replication of early 19th century British fictional narrative, with overt influence of Walter Scott and others, including fantasies, romantic dreams and desires, damsels in distress and exhibitions of virile violence and valour.

Understandably therefore the leader of the horde of intruders into the bedchamber of the beautiful Lachhmi is Zalim Khan and members of his Pindari horde. Breaking into Lachhmi’s room he carries her off in well-known classic gesture as he declares proudly, “‘Thou art mine, fair flower of India’, said Zalim Khan, and lifting up in his arms ran downstairs.” As the short story ends Lachhmi is re-united with her true love Anand Sing for a brief period. The description of the togetherness of the lovers can compete with contemporary chick lit and stag lit, “A thousand burning kisses were implanted on her delicately parted lips, which were answered only by the heaving of her bosom…Oh, tell me my love where am I.” Like in the earlier tale, this one too ends in tragedy.

Some of the other short stories too such as “An Oriental Tale” and “The Crusader” among others are remarkable for their use of medieval rhetorical ploys and plots and are illustrative of the immersion mode in which the colonised imbibed the domineering thrust of the coloniser’s culture and linguistic imperialism, so well analysed by Franz Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth.

Yet what truly distinguish the young Kylas’s fictional and non-fictional writing are a rational critique of his times and the exploitation of the natives by the East India Company. History can only reiterate that business corporations and multinational companies have profit by hook or crook as their sole objective and so Kylas in his essay “India under Foreigners” praises the Mughal Empire and its administrative efficiency and interest in settling in India and treating the conquered terrain as homeland.

While lauding the British for building roads, canals, bridges and formal education by setting up schools and colleges, Kylas rips off the mask of imperial pretensions as he writes, “The violent means by which Foreign Supremacy has been established and the entire alienation of the people of the soil from any share in the Government, nay, even from all offices of trust and power, are circumstances which humanity must ever regret…”

Also, a riveting essay is the one titled “Scenes in Calcutta”. The lament of the male middle-aged Brahmin bhadralok may remind readers of the fact that culture may often be interpreted as a process of cyclical progression and sometimes the past and contemporary times seem to replicate each other, “The age in which we live, is infected with the spirit of infidelity — high and low are deserting the standard of Hindooism.

But the cause of this is, the communication of European learning to the children of the East…But I predict those who have tampered with the wine cup and danced with the fair haired, blue-eyed light-footed damsels of the West will repent their folly, will be happy to undergo every penance to be considered hereafter a member of the Hindoo community.”

The Pindari Lover is not just about the writings of Kylas Chunder Dutt. The book is a rich memoir and a memorabilia. It includes illustrations and photographic reproductions of the pages and cover of the Dutt Family Album. It also includes poems by many members of the Dutt family from Govin and Greece Chunder Dutt to the poems by Aru and Toru Dutt among others, including the poems of Kalyan Chunder Dutt who has carefully researched and compiled the resources of the illustrious Dutt family. On one level the book is a document of the inherited legacy of an educated, cultured bourgeois family that had converted to Christianity, on another level the book exudes the editor Kalyan Chunder Dutt’s tender affection, love and family pride.

Kalyan Chunder Dutt has now gifted not only to his son Ishan Chunder Dutt but to the world a fascinating volume of collected and selected “Indian” writings in English, replete with vivid images and vibrant words that the members of the Dutt family of Rambagan, Calcutta, use with exemplary skill in sketching the cultural history of Bengal and Calcutta during colonial times.

The reviewer is former professor, department of English, Calcutta University