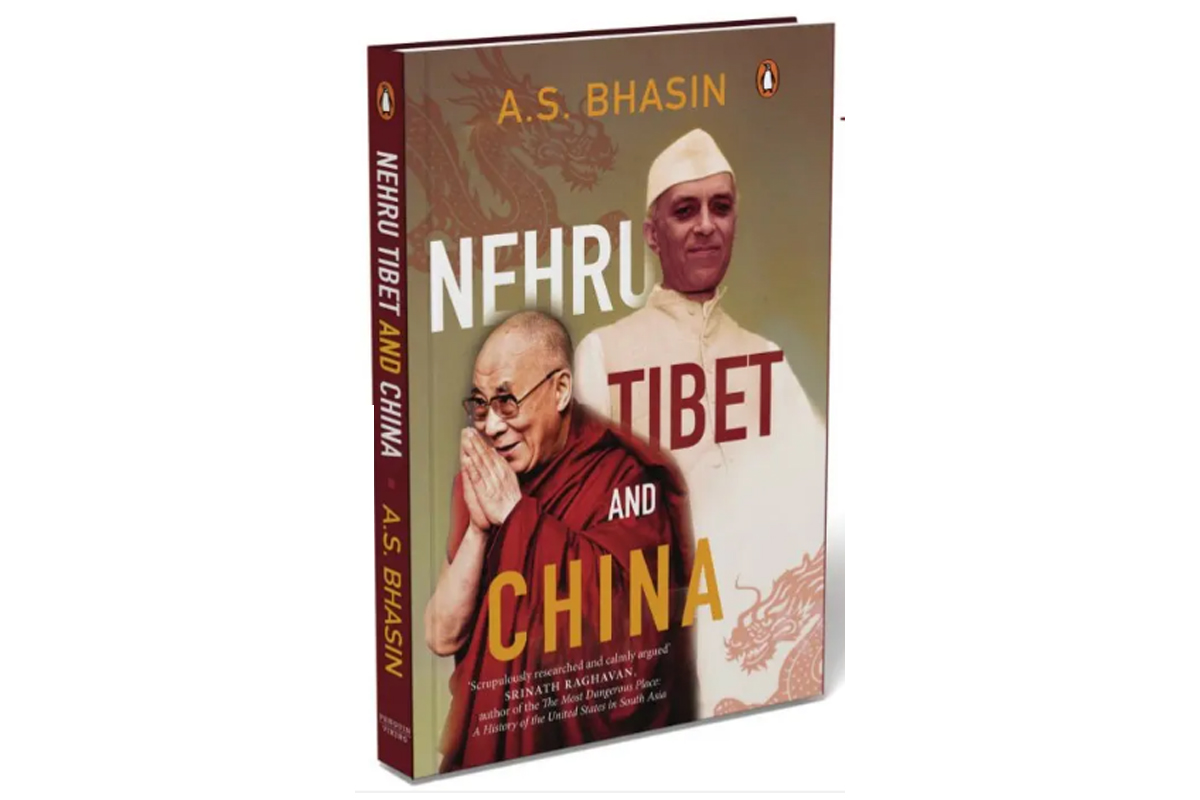

Many books have been written about Jawaharlal Nehru, the Dalai Lama and China. What is different with Avtar Singh Bhasin’s just released, Nehru, Tibet and China published by Penguin Viking, is that it has a fresh perspective on the Nehru regime and India’s relations with China, strongly supported by hitherto unpublished documents from the Union ministry of external affairs and the Nehru papers.

The book is focused on Nehru’s China policy in the context of Tibet during India’s formative years after Independence. Bhasin traces the roots of present tensions between India and China to the years soon after the two giants emerged as modern nation-states. It is challenging to comment in a few words about this 400-page book, so I will deal with three broad issues. The first is a background about Nehru’s attitude to Tibet and the Dalai Lama’s exile. In 1962, the Chinese military took complete control over the entire Tibetan plateau and Greater Tibet by humiliating India and stunning the world. Tibet left a vacuum by not occupying the areas between India’s then-existing North-eastern border and the new McMahon Line, and allowing Tibetans to settle.

Advertisement

On the other hand, Tibet claimed the return of Sikkim, Bhutan, Darjeeling, Ladakh and extensive tracts of territory that “had been gradually included in India in the past.” Beijing cites Lhasa’s demands during Sino-Indian border talks even today. It had forced an embarrassed Dalai Lama to repudiate the demands and declare that Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh was a part of India.

The second is Nehru’s foreign policy and the Sino-Indian border dispute, which has been going on for more than five decades. Records show that had Nehru listened to some of his mature advisers, the border issue would have been history. “Only if he (Nehru) had followed the advice he gave liberally to the Burmese Prime Minister to negotiate about his country’s borders with China and not adopt a rigid line, and settle them by handshake, India would have saved itself the ignominy of 1962.” Bhasin notes that “He did not even heed the advice of Khrushchev who, by his own country’s example, tried to bring home to Nehru the virtues of a tranquil border.”

Nehru guided India for a decade-and-a-half after Independence, and was unchallenged in his decisions on India’s foreign policy. By 1958, China began to make open claims and was engaged in aggressive military activity on several thousand square miles of Indian territory. The author argues that though Nehru had the stature and ability to persuade India to accept the formula suggested by Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai in 1960, he missed that opportunity.

China has border issues and territorial disputes with all its immediate neighbours and even, the far-away ones. Interestingly in 1960, China had offered to accept the McMahon Line in the North-east, provided India accepted China’s position in the Western sector. It has since withdrawn the offer and now claims Tawang while retaining Aksai Chin in the West. China’s new stand makes any settlement today more difficult than ever before. The best option is based on the status quo to the Chinese position in 1960, which Enlai repeated in 1979 to Atal Bihari Vajpayee, then Union minister of external affairs, and later in 1980 to an Indian journalist in an interview.

The third aspect is Nehru’s misconceived notions about Communist China and how he believed that it would not attack India until the end. Even after Chiang Kai-shek was deposed and the Communist China of Mao and Enlai took centre stage, Nehru continued to maintain this misguided belief. When the Chinese attack came in 1962, Nehru was devastated. He pleaded with United States President John F Kennedy for military assistance in a letter, virtually asking the U S to join the war.

The problem was that Nehru did not understand new China. “The old China was dead, but somehow Nehru insisted on building his relations with the new China on past foundations. It took some time, to his regret, to find contemporary China different from the old China he had known. In the process, he neither achieved peace nor Asian solidarity.”

Bhasin also presents a fascinating account of the negotiations that led to India becoming the first non-Communist Asian country to recognise the new government in Beijing. Documents reveal in detail the deterioration of the Sino-Indian relationship.

The author concludes that the Chinese attack was unrelated to territorial or boundary issues but rather, as Liu Shaoqi, then Chairman of the People’s Republic of China, asserted, “to demolish India’s arrogance and the illusion of grandeur”. He quotes Enlai’s explanation in 1972 to President Richard Nixon, “He (Nehru) was so discourteous; he wouldn’t even do us the courtesy of replying, so we had no choice but to drive him out. We had gone to war, justifiably in 1962, to teach India a lesson.”

The book provides rich material for scholars and researchers. A former director of the Union ministry of external affairs’ historical division, Bhasin is well-versed in the subject. It warrants mention that this is not the first book the veteran author has written. He has previously documented the relations between India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, China and Sri Lanka.

The reviewer is a senior columnist based in New Delhi.