‘The base of performance is acting,’ says Angad Bedi in an exclusive chat about latest show The Verdict-State vs Nanavati

There are so many films based on similar stories but are made in different forms by different people in the same space.

The author has sourced most of the information from newspaper archives and Internet sites and has painstakingly strung them together to give the readers as much authentic information about the case as possible. However, a little bit of professional editing could have increased the readability of the book … A review

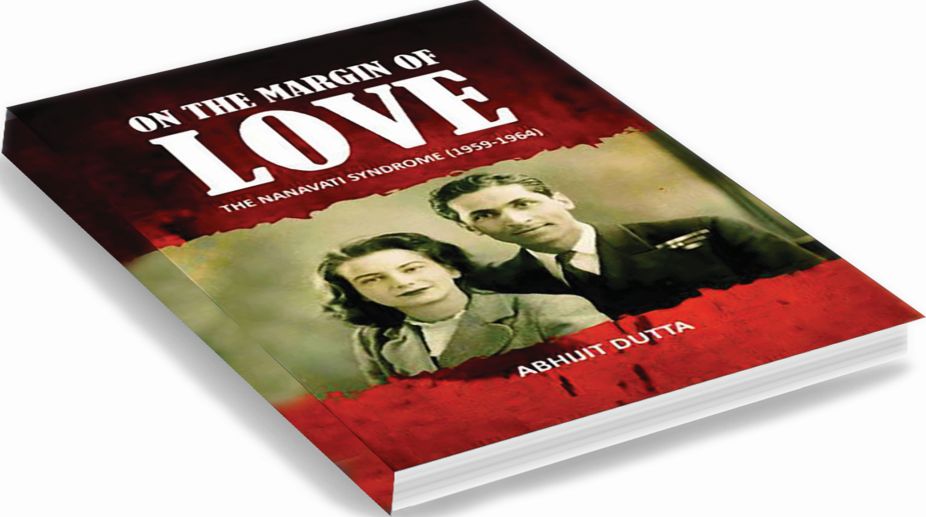

On the Margin of Love The Nanavati Syndrome (1959-1964) By Abhijit Dutta Readers Service, Kolkata, 2017

However sensational it might be, public memory is essentially very short. So remembering a particular murder case and its ramifications in court that took place several decades ago is well-nigh impossible.

The author of this book has done a lot of research and brought out the details of the sensational Ahuja murder case of 1959 that shook the conscience of the nation. The case has all the ramifications of a perfect Bollywood masala film.

Advertisement

Commander Kawas Manekshaw Nanavati who served in the Indian Navy became aware of the illicit love affair that his wife Sylvia was having with one Prem Bhagandas Ahuja, a notorious playboy-cum-businessman of Bombay of the 1950s.

Advertisement

It is said that this gentleman would target as his victims the lonesome wives of military or naval personnel on long duties away from home, or other high society women long estranged from their husbands.

When Sylvia herself confessed to her husband about the affair, the commander went and borrowed a fully loaded revolver from his ship on flimsy grounds, and headed straightway to Ahuja’s flat. After shooting Ahuja down he subsequently went and surrendered to the police.

Till now it seemed as a clear case of revenge by the forsaken husband but the interesting ramifications to the case began when Nanavai’s trial began at the Bombay Sessions Court. The moot point discussed was whether it was a premeditated murder or a case of accidental firing during a skirmish with the victim.

The chief public prosecutor stated that he would appeal to the jury to frame Nanavati under the lesser charge of culpable homicide not amounting to murder. When the nine-member jury gave a verdict of “Not Guilty” to Nanavati by a majority of eight to one, there was an uncanny feeling among many that the Jury had been unduly manipulated or influenced. As a consequence, trial by jury was stopped in India after this case.

In spite of public sloganeering for the release of the commander, the case moved to the Bombay High Court. After a lot of further proceedings when Nanavati was almost convicted for murder, an interesting turn in the case took place.

Sri Prakasa, the then Governor of Bombay, under the suggestion of the Nehru government suspended the sentence of the Bombay High Court for life imprisonment till the matter came up for hearing at the Supreme Court.

The full bench of the High Court of Bombay therefore failed to terminate the Governor’s order issued under Article 161 of the Constitution. This gave Nanavati adequate respite and he was lodged not in an ordinary jail but kept in Naval custody.

The Supreme Court judgment showed all the straits of rationality that marks an impartial hearing of facts. Later even though the Supreme Court upheld the sentence of the High Court jailing Nanavati for life, a state pardon issued after three years by the then Governor of Maharashtra and Jawaharlal Nehru’s sister, Vijaylakshmi Pandit, who was Sri Prakasa’s successor, worked wonders to bring out the criminal from jail, culminating in his eventful emigration to Canada in 1964 with his family and thereby to final freedom.

The author has sourced most of the information from newspaper archives and Internet sites and has painstakingly strung them together to give the readers as much of authentic information about the case as possible. He has also sourced information from a novel entitled The Death of Mr Love (2002) written by an Indian English novelist called Indra Sinha.

After reading the book one gets a clear picture of how powers that be or sheer good fortune or the ramifications and nitty-gritties of our legal system sometimes help an accused person on trial win undue favour and freedom from punishment.

However, according to this reviewer, a little bit of professional editing could have increased the readability of the book which at certain sections tends to get mired in repetitions. Also the random use of italicisation should have been avoided. On the whole it remains a laudable effort.

The reviewer is professor of English, Visva-Bharati University

Advertisement