Jahangir, the least known of the Great Mughals, was a fascinating person. Mirza Nur-ud-din Beig Mohammad Khan Salim, who took the name Jahangir after accessing the Mughal throne, is most known as the son of Akbar the Great. Mostly remembered for his personal life, rather than his professional achievements, Salim, which means ‘undamaged’ or ‘whole’, was an enigma, according to a new book.

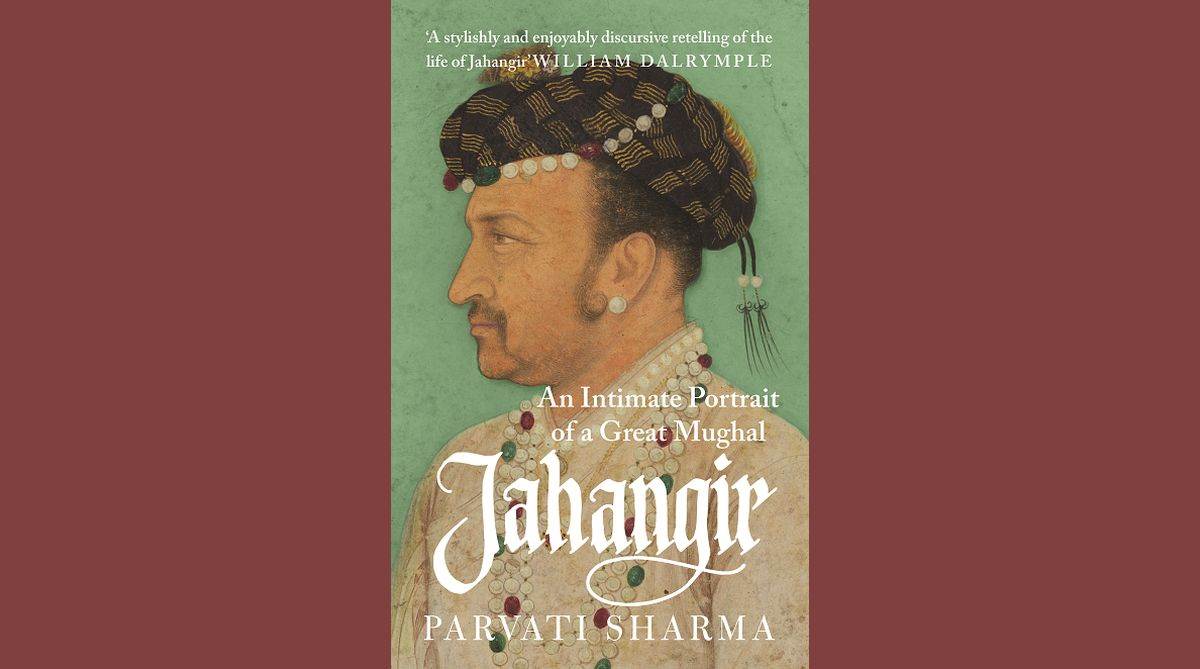

An Intimate Portrait of a Great Mughal Jahangir, by Parvati Sharma, tells the story of a man more famously known for his relations to others. Not as Akbar’s son or Noor Jahan’s husband, the book tries to show him as Jahangir, the fourth Mughal emperor.

Advertisement

Excerpts from the book:

When Akbar’s nameless Rajput wife-eldest daughter of Raja Bihari Mal Kachhwaha of Amer, called Jodha Bai (incorrectly) and Mary of the Ages, Mariam-uz-Zamani (formally), whom Akbar had married seven long years ago in the manner of kings, en route from a hunt-became pregnant, he took her to live in the Sheikh’s home. Partly of course, this was so that the queen and her unborn child might be as close as possible to the Sheikh’s protective blessings; but partly, also, it was to keep the pregnancy far from gossiping streets and stem the tide of ‘curious stories’ that had begun to dog the emperor’s childlessness.

So it was that the Rajput queen of a Mughal monarch moved from the royal fortress of Agra into the hillside home of a Sufi saint. These new arrangements were not, as one can imagine, without their challenges. A bit of gossip from the time suggests that the Sheikh’s daughters-in-law were particularly unhappy by the sudden-and seemingly constant-presence of an anxious emperor in their midst. When the Sheikh’s sons and daughters brought up the marital strife they were having to endure at the hands of their flustered wives, they received little redress. After all, now that Akbar’s own wife was lodged in his zenana, the Sheikh could hardly deny the emperor access to it; and Akbar himself just laughed off at their complaints. ‘There is no dearth of women in the world…seek other wives!’

The exigencies of propriety would not stand between the emperor and his heir, nor would the dark designs of fate. One day, the baby stopped kicking. At first, perhaps, the queen felt only a nagging strangeness, a sense of something missing; then, as it dawned on her, her mind fell numb and her body shivered under its skin; she could not speak and she clutched for her nurses. ‘In a dither’ writes Salim, ‘the nurses reported the situation to His Majesty’

What could Akbar do? He’d promised a pilgrimage to Ajmer, he’d submitted to the protection of the Sheikh, why now this final test? Perhaps he was meant to give something up, something he loved for something he craved-perhaps it was a sacrifice that was demanded of him.

Like most royals, Akbar loved to hunt, and the kind of hunting he loved most was that rare and spectacular sport of hunting with cheetahs. Cheetahs, tame and trained, were among the jewels of Akbar’s menagerie, riding in stately array into hunts, sitting straight-backed and alert upon carts from which they would spring after their prey when released, padding softly within striking distance to make their final, lethal leap. Much like their emperor, they rarely missed.

What did it matter now, though, the thrill of the hunt? This was time for new life, not death! As it happened, the day was a Friday, and Akbar vowed that if only his baby would move again, never on a Friday would he hunt with cheetahs.

And never again he did: mid-morning on a Wednesday, in the monsoon of 1569, Akbar’s nameless queen delivered the boy who would, one day, sit on Akbar’s throne; half-Mughal, half-Rajput, they named him Salim- intact, unblemished and whole.

An Intimate Portrait of a Great Mughal Jahangir will be released on November 6.