Francis Ford Coppola: “I started Hollywood’s sequel obsession and I’m sorry”

Francis Ford Coppola reflects on how 'The Godfather Part II' fueled Hollywood's sequel obsession, calling it an unintended legacy.

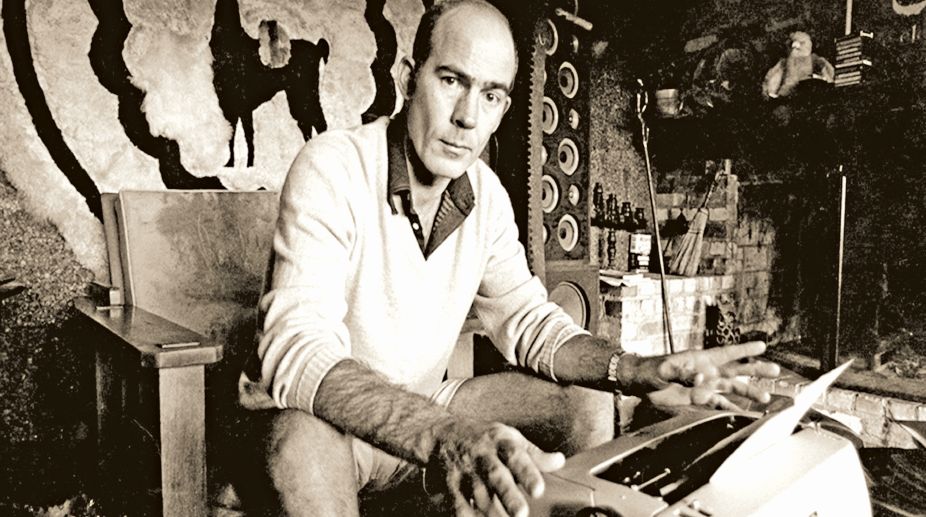

Journalist Hunter S. Thompson sits at his typewriter at his ranch circa 1976 near Aspen Colorado. (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

Who killed Hunter S Thompson? Nobody killed Hunter S Thompson, nobody but himself. At 5.42pm on Sunday 20 February 2005, he shot himself with a gun at his home of Owl Farm, near Woody Creek in Colorado, US.

Thompson was 67 when he died, with his son Juan, who was visiting with his wife and son for the weekend, in the next room. That was 17 years too long, according to the note Thompson left for his wife Anita, who was out that day.

Advertisement

Thompson had phoned her to ask if she’d come home to help him write the column he did every week for the sports channel ESPN. He’d already written what Rolling Stone magazine later published as his “suicide note” — a few short, terse sentences including “No more games. No more bombs. No more walking. No more fun”.

Advertisement

Anita heard what she thought was the rattle of the typewriter keys as she killed the call. From the police and pathology reports and the witness statements of his son as to the time of the suicide, it was determined that this wasn’t Thompson’s typewriter at all. It was the sound of him cocking his gun.

But, who killed Hunter S Thompson? And why do we ask? Because that’s the title of a new book from US publisher Last Gasp, edited by Warren Hinckle, the former editor of the now-defunct Ramparts magazine, who shared an office with Thompson during the 1970s and 1980s.

Except it isn’t just a book. It’s a testament, an appreciation, a homage that’s as crazy and dangerous as the man himself, the size of a headstone and with a kick like a semi-automatic.

Never mind who killed Hunter S Thompson, who was he, anyway? He was a journalist, mainly, with a side order of guns, booze and drugs. Or maybe that was the other way round.

He was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in July 1937, to a family that was middle-class but plunged into poverty by the death of Thompson’s father. The young Thompson never made it through high school, due to being banged up in prison for his involvement in a robbery, and after that he joined the United States Air Force.

Thompson wanted to fly, but they wouldn’t let him, so he moved around from base to base, Texas to Illinois to Florida, and started moonlighting as the sports editor of a local paper, sans byline as military rules forbade servicemen holding another job.

Eventually, in 1957, he left early with an honourable discharge, in which his commanding officer observed, “Sometimes his rebel and superior attitude seems to rub off on other airmen staff members.”

For the next seven or eight years Thompson shinned up the greasy journalism pole, working his way around the States, getting as far as Puerto Rico. He hitchhiked across the US, ending up in bohemian Big Sur in 1961.

The following year Beat founding father Jack Kerouac would publish his novel about fire-watching up in the Californian mountains at Big Sur, but Thompson had already blown through it like a Santa Ana wind, writing his first magazine feature on Big Sur’s artsy liberal culture and in the process pissing off the residents no end.

He married his long-time girlfriend Sandy Dawn Conklin in 1963, and they had Juan. They divorced 17 years later. They moved to San Francisco, which was growing its hair and loosening its belt and turning on to hippy drug culture, and Thompson found this mighty appealing.

After years of writing straight news stuff for the big papers, he turned his attention to the burgeoning underground press movement, and began to write for the likes of the Berkeley-based independent paper Spider.

Hunter S Thompson perhaps didn’t know it then, but he was about to get the shit beaten out of him by a bunch of Hell’s Angels and, in the process, invent a whole new form of journalism.

Warren Hinckle’s introduction to Who Killed Hunter S Thompson runs to almost 200 pages. It is, as the cover trumpets, a book in itself. It opens with a scene set in the office of Hinckle’s magazine, Ramparts, in San Francisco’s North Beach. Hinckle had a pet monkey in his office, called Henry Luce, which was also, not coincidentally at all, the name of the founder of the twin colossi of American mainstream magazine publishing, TIME and Life magazines.

Thompson rocked up at the office one day, dumped his bag, and went out with Hinckle for dinner. When they got back, poor old Henry Luce was off his nut. He’d burgled Thompson’s rucksack and imbibed what he found there. “No one could pacify him,” writes Hinckle. “It took a day and a half for him to slow down. ‘Goddam monkey stole my pills,’ Hunter said.”

This is the legend of Hunter S Thompson. The gun nut who smoked with a cigarette holder, who casually carried around enough drugs to send a monkey insane.

The man who opened his perhaps most famous book, 1972’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, with the lines, “We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold. I remember saying something like ‘I feel a bit light-headed; maybe you should drive’… And suddenly there was a terrible roar all around us and the sky was full of what looked like huge bats.”

Fear and Loathing, first published in 1971 in Rolling Stone magazine, was the thing that brought Thompson to public attention, probably made him public enemy number one in a lot of households, the epitome of the man that mothers warned their daughters about.

It was the insane account of invading a police drugs convention while armed with enough drugs to send an infinite number of monkeys batshit crazy. It wasn’t all fun and games, though; it was about how, in Thompson’s eyes, the hippy dream had failed and died. It was about the dark heart of America.

Johnny Depp made a movie of it in 1998, taking the role of Thompson’s alter ego, Raoul Duke. In 2005, Depp would finance Thompson’s dying wish; for his remains to be shot out of a cannon at his funeral.

Fear and Loathing was gonzo journalism. But what is that? Hinckle says, “Gonzo journalism is the unedifying concept of the reporter as a proactive part of the story with proportionate emphasis on the imaginative and comics as the real.” In other words, to do what is hammered out of every reporter at every journalism school. You are not the story. You are an invisible witness, a bystander, and an observer of events and an imparter of facts.

Hunter S Thompson first properly broke journalism in 1965 when he was hired by The Nation magazine to write about outlaw motorcycle gangs such as the Hell’s Angels.

Thompson turned in the piece and it generated a flurry of interest from book publishers wondering if he could sustain this topic over the length of a book.

So for the next year Thompson got in with the Oakland chapter of the Angels, in particular their president Ralph “Sonny” Barger. He drinks booze with them, takes drugs with them, rides with them, and invites them back to his house, to the dismay of his wife and neighbours.

He felt at enough ease with them to berate one of the members who Thompson had been told was beating his wife. That earned him a “stomping” from several Hell’s Angels, and effectively brought his association with them to an end.

But it opened the doors for Thompson, despite the fact that he’d stomped on the rules of journalism just like the Angels had stomped him, and put himself front and centre in the story.

Suddenly people wanted more of this journalism. It didn’t have a name, though, until 1970, when Scanlan’s Monthly, edited by Warren Hinckle, ran a piece written by Thompson and illustrated by the man who would become his long-term friend and collaborator, the artist Ralph Steadman.

The feature was called “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved” and is widely accepted to be the piece that gave birth to gonzo journalism.

The phrase was coined by the writer Bill Cardoso, who recalls the moment in Hinckle’s book. He had just read the Kentucky Derby piece and hadn’t seen anything like it before, the way the journalist swaggered into the narrative, waved at the reader from the middle of it all, even changed the way things would have, should have, gone.

“I was in awe at this pioneering accomplishment and said so in a note, telling him, ‘I don’t know what the f**k you’re doing, but you’ve changed everything. It’s totally gonzo.’ Hunter ran with it. That’s how the word was coined.”

Thompson’s star flared brightly after that, but it was an intense, arguably short-lived supernova. After Hell’s Angels he was in great demand, and did a lot of work for Rolling Stone, huge rambling political pieces on the election campaigns of Richard Nixon and his rival, George McGovern.

He was sent to Africa to cover the famous Rumble in the Jungle world title fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in Zaire in 1974. Thompson stayed drinking in the bar of his hotel with Ralph Steadman, and missed the fight.

Certainly, his star seemed to have faded at Rolling Stone, and assignments became fewer, and those that he did get were often cancelled… one time Thompson had gone to Saigon to report on the closing days of the Vietnam war, but his commission was scrapped while he was there, leaving him high and dry.

Probably by the 1980s he had become a little more reclusive, after his divorce in 1980, and Owl Farm began to resemble a compound where he was gearing up to sit out some apocalypse or other.

The writer E Jean Carroll visited him in the early 1990s, which resulted in the 1993 book Hunter. It details then incident a couple of years earlier when former porn queen Gail Palmer, after visiting Thompson, filed a complaint of sexual assault. She also said there’d been copious cocaine use.

The police visited and found cocaine, and plenty more drugs. Enough to send a monkey crazy. They also found dynamite. The charges were dismissed after a pre-trial hearing.

Thompson was beginning to claw his way back into the limelight, helped five years later by the movie version of Fear and Loathing. Thompson had also regularly “appeared” in the long-running newspaper strip Doonesbury, styled as “Duke” by creator Garry Trudeau. There’s a Trudeau strip in Hinckle’s book, a psychedelic, psychotic tribute drawn in the days after Thompson died.

Maybe it was a mistake, Thompson shooting himself. A grandstanding stunt, gone wrong. An accident. In the seven years between Depp’s portrayal of him on screen and his death, his star began to rise and burn brightly again.

New Rolling Stone commissions, new books, a publication for his novel The Rum Diary (and subsequent movie adaptation) which he’d written in his younger days. He’d married his assistant, Anita Bejmuk, in 2003. Maybe he never meant to kill himself.

No. In a piece entitled I Knew He Meant It in the new book, his long-time friend Ralph Steadman writes, “Hunter said these words to me many years ago. ‘I would feel real trapped in this life if I didn’t know I could commit suicide at any time’. I knew he meant it. It wasn’t a case of if, but when. He didn’t reckon he would make it beyond 30 anyway, so he lived it all in the fast lane. There was no first, second, third or top gear in the car — just overdrive.”

Who killed Hunter S Thompson? Sure, he pulled the trigger himself, but maybe it’s not right to say nobody did it. Perhaps when you’ve lived your life staring down the American Dream and unflinchingly seeing it for the twisted, scabrous thing it is, or can become, then maybe you let a part of it into you. The abyss gazes also.

Maybe America killed Hunter S Thompson. It’s a shame that he didn’t stick around, though. He might have lived a life brimming with fear and loathing, but can you just imagine what the godfather of gonzo, 80, and cranky and unrelenting, would have made of Donald Trump’s America?

Come back, Hunter S Thompson. We’ve never needed you more.

The Independent

Advertisement

Francis Ford Coppola reflects on how 'The Godfather Part II' fueled Hollywood's sequel obsession, calling it an unintended legacy.

Johnny Depp makes a comeback in the historical drama "Jeanne du Barry," captivating audiences with his stellar performance.

The band eventually decided to postpone their show because of the gravity of the whole situation and out of concern for Johnny Depp’s health and safety.

Advertisement