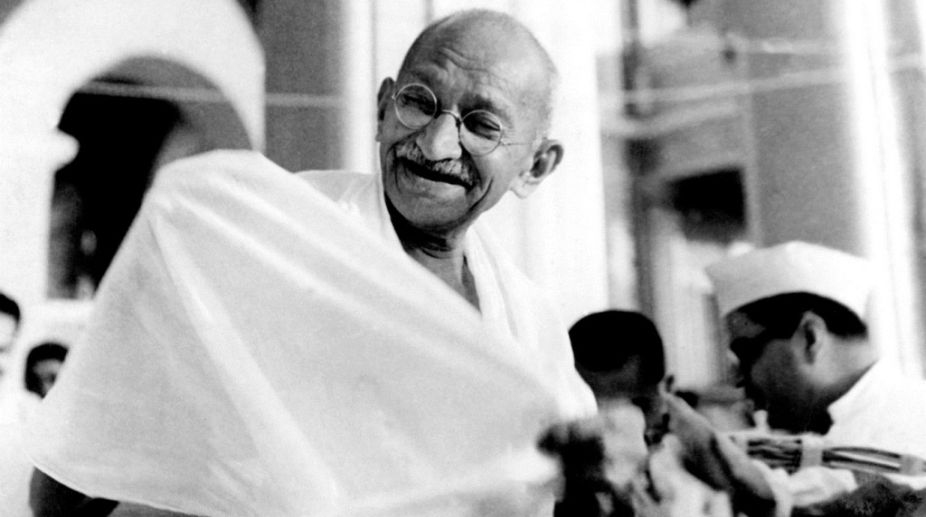

Creativity and inspiration are the two defining factors for most writers and their craft. But while creativity is largely the process of generating original ideas, inspiration is random. Sometimes it comes from the simplest of things. Like the life of Mahatma Gandhi. Poetry, prose or drama; fiction or nonfiction — Gandhi is everywhere.

There are indeed only a handful of iconic personalities who have caught the imaginations of as many writers as Gandhi has. And one is wonderstruck at the diverse set of books that have been written on him or are inspired by him. Even 70 years after his death, the process has not stopped, but only gained momentum.

Advertisement

From Mulk Raj Anand to Sarojini Naidu, Dominique Lapierre to George Orwell and Khuswant Singh to V.S. Naipaul, almost all “during-Gandhi”, “post-Gandhi” and contemporary writers have somewhere referred to the life of “Bapu” in their works. Thus, they have brought different interpretations to his sayings, sketched fictional characters on his principles and composed verses on his thoughts.

Sarojini Naidu, in her sonnet on Gandhi, describes him as an eternal lotus who is a source of guidance and strength for billions: “O mystic Lotus, sacred and sublime/ In myriad-petalled grace inviolate/ Supreme o’er transient storms of tragic Fate/ Deep-rooted in the waters of all Time…”

But Indian writing on Gandhi and Gandhism has also undergone tremendous change during this process. From the almost mystical being of the during-Gandhi era to a historical being with human vulnerabilities.

Gandhian scholar Vashist Bhardwaj finds the works of R.K. Narayan critical for his exploration of Gandhi as subject. “Known for his direct approach in handling his subjects, in Gandhi’s case too, Narayan has used his wit at its best to ‘demahatmise’ Gandhism. For instance, Gandhi is seen as an oblivious yet dominating character in ‘Waiting for Mahatma’ with eyes closed to what is around and busy playing the dynamics of ‘self’. In Narayan’s ‘The Vendor of Sweets’ too, Jagan, the protagonist, comes across a hypocrite Gandhian, symbolising Gandhi’s failure to reach the masses,” Bhardwaj noted.

The post-1990s’ writings have seen greater concentration on Gandhian politics in writings on him. If B.R. Nanda is all praise for Gandhi’s politics, Sunil Khilnani is just the opposite.

Early foreign writings on Gandhi include the works of French writer Rolland Romain, Danish writer Ellen Horrup, American and English writers like George Orwell and Edmud Jones, among others. Romain, in “The Man who Became One with the Universal Being”, saw Gandhi as an ideal nationalist and called upon him to enlighten the youth of Europe. Similarly, Pearl S. Buck warned: “Oh, India, dare to be worthy of your Gandhi.”

On the other hand, George Orwell puts Gandhi to trial, describing him as a “humble, naked old saint sitting on a prayer mat, attempting to shake the British Empire by utter spiritual power”. Orwell refers to him as the “shrewd person beneath the saint” and asserts that his ideals of spirituality, spinning wheel and vegetarianism had narcissist undertones. However, Orwell also recognises the praiseworthy elements in Gandhi and writes: “Even Gandhi’s worst enemies would admit that he was an interesting and unusual man who enriched the world simply by being alive.”

In poetry, it is Herrymon Maurer’s reflections that have attracted most attention. “During a second period of pause/Gandhi went on with his teaching/East and West looked at him/Followed him, and yet misunderstood him,” Maurer famously wrote to summarise Gandhi’s life.

To note the rising presence of Mahatma Gandhi in the world of words, an extensive literary survey titled “Gandhi in Creative and Critical Imagination” was conducted in 2012 and published in the International Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities by Sandhya Saxena, vice-principal of Bikaner’s Jain Girls College.

“India in contemporary times is a stage set for Gandhi and Gandhigiri. Mahatma Gandhi permeates fiction as well as non-fiction in Indian writings, both in English and other languages. Gandhi is redefined in ways that are quite contemporary. Whereas in some cases there is an attempt to grapple with Gandhi and ultimately accommodate him, in other instances nothing of Gandhism remains unchallenged. Whatever be the case, in creative writings there is a sense of strong involvement as the writers pen Gandhi and Gandhism,” Saxena maintained.

At a time when a considerable part of Bapu’s presence is contrary to what he stood for — roads named after him serve as begging tracks for starving men, women and children while his fabric and quotes are mere means to woo votes — it is perhaps in these pages of Gandhian literature that Bapu and his ideals are still alive.