Education is the driving force behind the most significant transformations in society: Vice-President

Jagdeep Dhankhar was speaking at the convocation of Mata Harki Devi Educational Institute in Odhan and JCD Vidyapeeth in Sirsa.

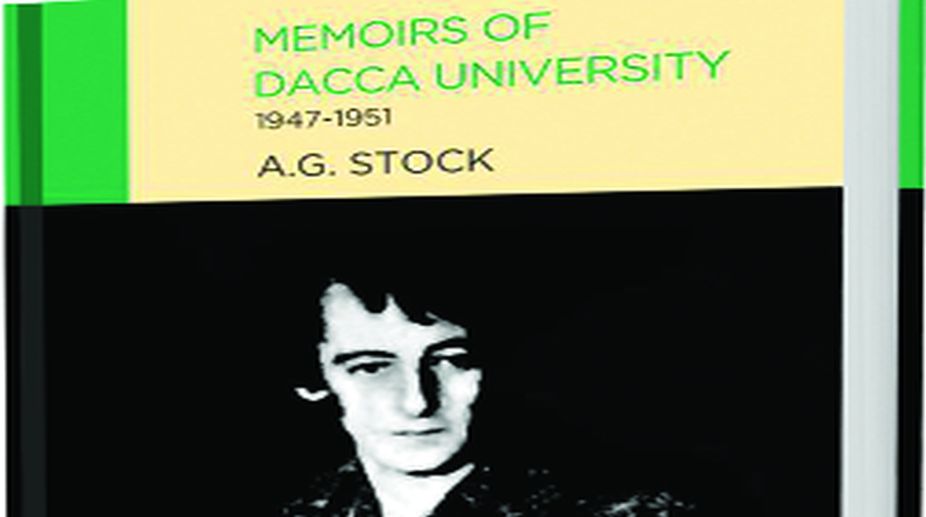

Memoirs of Dacca University 1947 - 1951 By AG Stock Edited by Khademul Islam Dhaka: Bengal Light Books, 2017

A young student studying English Honours at Oxford got herself hard at work in colonial freedom movements and was at that time the only European student interested enough in India to go fairly to the Oxford Majlis (the anti-colonial student forum) debates on Sunday evenings, and venture to speak there sometimes.

She had friends in common, and had told some of them that she wanted to teach in India but not till it was a free country. Her sympathies extended to others besides colonial subjects who were targets of the state’s repressive apparatus.

Advertisement

So, when in early 1947 two vacancies were advertised in The Times Educational Supplement, one for a lecturer in English at Makerere College, Uganda, and the other for a professor of English at the University of Dacca in East Bengal, she applied for both.

Advertisement

She decided on teaching “literature in one of the emerging countries”. At that time she was 45 and teaching as a part-time lecturer in English in a London training college and she finally accepted to teach in East Pakistan.

Soon we find Amy Geraldine Stock, or Miss AG Stock as she was popularly known, on board the SS Franconia bound for Bombay and arriving in Dhaka. As head of the English department she taught there at the university from 1947 to 1951.

After Dhaka she taught in India, for five years at Punjab University, at the University of Rajasthan, Jaipur from 1961to 1965, at Calcutta University, and at Makerere University in Uganda.

After 20 years as a post-colonial professor in English, she retired to a quiet English village and there in 1970, began writing her reminiscences for the pleasure of remembering how Dacca University, with its exasperations and good company and indescribable charm, had welcomed her so unexpectedly and taught her so much a quarter of a century ago.

The result of her effort was a book, Memoirs of Dacca University 1947-1951, published originally in Dhaka in 1973 by Green Book House (now defunct). A few years ago the editor of Bengal Light Books chanced to pick up the paperback volume from a second-hand book shop in Dhaka, a volume that had been ravaged by time and spilled tea.

It was a product of the era of letterpress and manual typesetting and realising its worth soon decided to republish it. So in 2017, the memoir has now come out in its new avatar with a foreword by Kaiser Haq. The publisher also notes that this memoir is no lacy tale of a memsahib embarking on a last fling with the vanishing colonies.

It was an account of Miss Stock’s stay from 1947 to 1951 at the University of Dacca. Bangladesh then was the newly-born East Pakistan, where conditions in the immediate aftermath of the Partition were very unsettled. All around her swirled an intellectual and political ferment that inevitably drew her in, resulting in a book, without peer, about those days by a remarkable woman.

Pakistan was born as the homeland for the Muslims of the subcontinent but very soon there was trouble in paradise. The central government based in West Pakistan began to impose a rigid Islamic identity on the Bengalis of East Pakistan by launching frontal assaults on their language and culture, sparking a fierce resistance.

Dhaka University was the site of the initial battles as well as the primary centre of the opposition. Professor Stock, driven in her radical political temperaments and beliefs, threw her lot in with the underdogs. It is this close engagement that drives her narrative at every instance.

As, say, when the Pakistan state sought to Islamicise schools and college syllabuses and curricula, otherwise arid educational board meetings turned into battlegrounds over secularism, minority right and academic standards, Professor Stock’s awareness of the undercurrents gives her accounts of those meetings startling colour and movement.

She clearly assesses the situation when she writes, “As a way of consolidating the new state, nothing could have been more stupidly inept than West Pakistan’s attempt to make Bengali take second place in their lives to Urdu.” By the end of August 1948 she felt that the Intermediate had become in her jaundiced imagination “the symbol of the vast practical joke that human society plays on itself.”

Passages from her memoir recount the marches, demos and protests of students. Whole sections are lit from within fellow feeling for her colleagues, students, acquaintances, and even university sweepers on strike over better pay. Her cook Abdul Huq and Kalipada, the departmental chaprasi and his son do not inhabit the margins of the book but live as fully-defined figures in their own right.

She visits a colleague in jail, arrested on flimsy charges, to try to free him; she stands guard in the women’s hostel during communal riots. She fulminates, as is her right, against certain Bengali ways and habits of mind. And she bores deep into the issues of poverty, identity and religion of a deeply traditional social order. “Imperceptibly, one grows used to the East,” she writes in her memoir and states that when she went to visit her mother in New Zealand, she did not find herself hankering to stay on there. Bengal, where she would always be half a stranger, still had hold of her.

In the introduction to her book Miss Stock clearly mentions that it is a memoir, not a history, and makes no claim to a historian’s detachment or research. But she clearly mentions that however patchy and impressionistic, the story in her journal and the memories it evoked were, as far as they went, authentic, and “might throw at least a sidelight on the way the catastrophe started.” She decided to carry it on to the moment when she left the scene, living as far as possible in memory and trying to keep hindsight distinct from what she had seen and thought at the time.

The book is also valuable and historically significant because it gives an insight into the causes leading to the Liberation movement. There is much of interest in what one could call the ethnographic aspect of the book. Soon after she realised that she was under surveillance and that her private correspondence was being read with disapproval by intelligence agencies, Miss Stock decided to apply to Punjab University, taking care to have her application posted in Calcutta by a friend going there.

She describes her departure thus, “Like Abdul, colleagues and students seemed to know what I had vaguely surmised, that the stars were against my staying, but they made me feel that I would be missed from their world. It is the way with departures — I was going of my own choice, but it began to seem incredible that I had chosen to leave so much good comradeship, so many shared enthusiasms. But the train screamed, shuddered and moved, and the fading crowd on the platform faded out of sight.”

Miss Stock heard of the Ekushey killings in 1952 soon after she moved to Punjab University. She visited Dhaka later that year, and again a few years later when she was teaching in Calcutta. Incidentally, she came to Dhaka for a second stint around the middle of 1972 and left in mid-1973.

Unlike her earlier visit, this time it was the new country of Bangladesh. But unfortunately student agitation was still rife and it seemed that independence had not altered the adversarial stance of students towards authority. As an outsider, she was not in a position to pass judgment on the issues, but she did know that the university as an institution was meant to concern itself with something else.

This volume will interest readers who want to get a slice of history of our subcontinent from an objective outsider’s point of view. The impeccable English of Miss Stock is an added attraction. What strikes one after going through this memoir is how much of her observations about the educational system then is still extant now on both sides of the border.

The reviewer is Professor of English, Visva-Bharati University

Advertisement