Eloped with boyfriend from Kurukshetra, teenager rescued in North East Delhi

However, according to the police, the girl denied that she was kidnapped and clarified that she checked in at the hotel of her own accord.

The book, written by Mumbai-based journalist Arita Sarkar, includes some cases in which the victims never returned home.

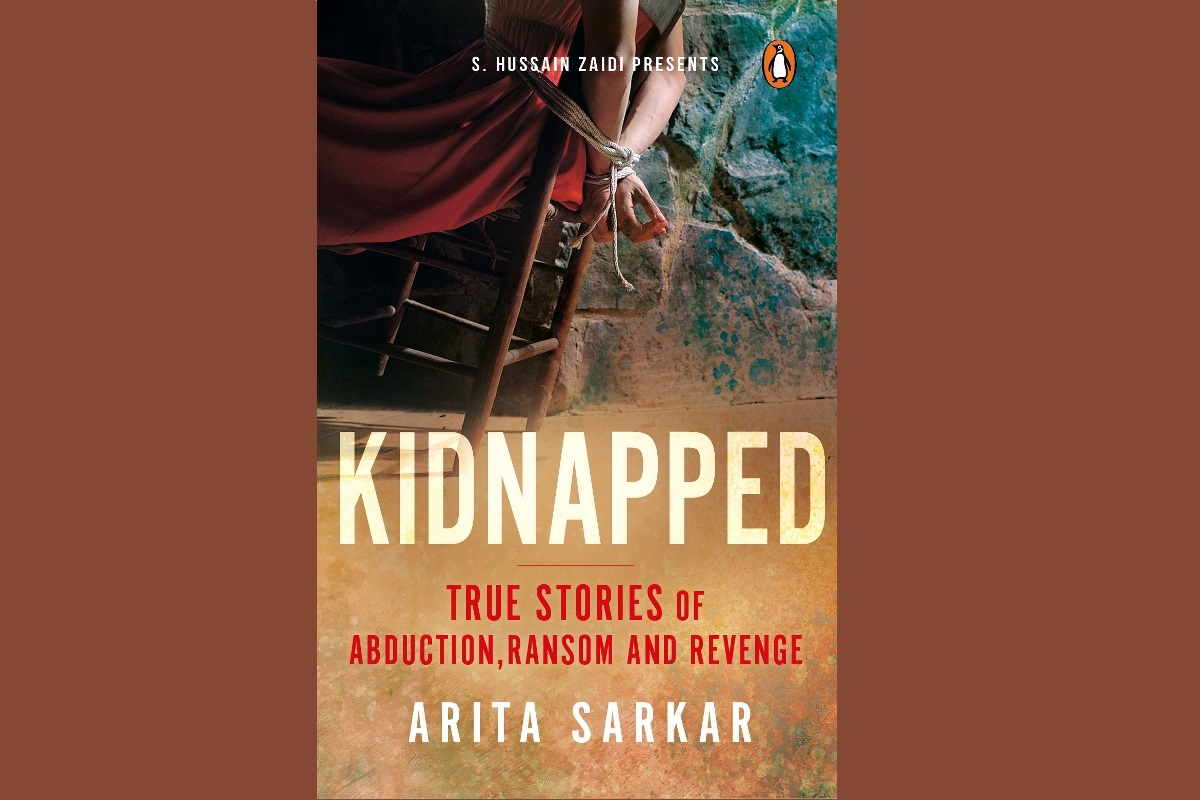

(Photo: Penguin/SNS)

‘Kidnapped: True Stories of Abduction Ransom and Revenge’ documents 10 cases of child kidnappings from across the country. The book, written by Mumbai-based journalist Arita Sarkar, includes some cases in which the victims never returned home.

Why children? Because approximately ten people were abducted every hour in India in 2016. Of them, six were children.

Advertisement

Besides investigating the details of the disappearance of each child, the stories also delve into the trauma that the victims’ families went through, as they waited in the hope that their children would return.

Advertisement

The book has been praised by former Delhi Police Commissioner Neeraj Kumar and former Mumbai Police Commissioner Julio Ribeiro.

Sarkar has been a reporter at The Hindu, Mumbai Mirror, the Indian Express and Mid-Day. Her interest in cases concerning the Juvenile Justice Act, the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act and child rehabilitation led her to research and write a book about the widespread kidnapping of children in India.

Published by Penguin Books, the 234-page ‘Kidnapped’ is priced at Rs 299.

Chapter 10: Anant Gupta, Noida

On 19 November 2006, twenty-year-old Chhatrapal Singh, who had dreamt of being an actor, found himself in a police lock-up, being interrogated by Sub-Inspector Sushil Kumar Dubey over the kidnapping of a three-year-old boy from Noida on 13 November.

‘Kyun, be, teri haiseeyat hai kya pachaas lakh rupaye maangne ki (So, you think you have the status to demand Rs 50 lakh)?’ Dubey thundered at the cowering man.

‘Nahi, saab, maine toh sirf paanch lakh mangi thi. Unhone pachaas lakh suna (No, sir, I had asked for only Rs 5 lakh. She heard it as Rs 50 lakh),’ replied Chhatrapal.

If it was comedy acting he aspired to, he certainly had the timing for it. The missing three-year-old boy, Anant, was the son of Naresh Gupta, then managing director of Adobe India. Around 9 a.m. on 13 November, a Monday, Anant stepped out of his home in a gated society in Noida’s Sector 15A to catch his school bus at 8.50 a.m. The bus stop was just 50 metres away and with Anant was Seema Devi, the Guptas’ domestic help. A pre-nursery student at Lotus Valley School, Anant was eager to meet his friends.

Barely forty steps from the gate, Seema noticed two men on a black Hero Honda Splendour. They stopped in front of Seema and Anant, blocking their path. In a split second, the man riding pillion grabbed Anant and the bike sped away. Instinctively, Seema screamed for help and her cries were heard by the guard, Kameshwar Ojha, and passers-by. Ojha and other people tried in vain to chase down the bike, which made a quick U-turn and disappeared through one of the society’s main gates.

Unfortunately, neither of Anant’s parents were home at the time. His mother, Nidhi, had left the house at 8.30 a.m. for Marwah Studios in Sector 16A, where she was pursuing master’s course in mass communication, while her husband, Naresh, was on his way back from a business trip to San Francisco.

Without wasting any time, Kameshwar quickly telephoned the police and told them what had happened. Within a few minutes a police team arrived at the house, and by 9.40 a.m., a kidnapping complaint had been registered at Sector 20 Noida police station.

Nidhi heard the news from a neighbour about half an hour later while she was in her class and rushed back home. By then, the police had begun questioning eyewitnesses, an Nidhi and her relatives could do little but wait anxiously.

Naresh was in Hong Kong, waiting to board a flight to Delhi, when his brother-in-law, Lalit Kumar Gupta, called to tell him what had happened. After the initial reaction of shock, he knew he had no time to waste. He began calling his friends at once, who rushed to the airport in Hong Kong.

It wasn’t long before word spread to senior police officers, politicians and even the Prime Minister’s Office. Everyone involved knew that the stakes were high. Meanwhile, with Anant sandwiched between them, the kidnappers, Chhatrapal and his accomplice, Pavan Pal, rode 400 kilometres to Hardoi. On the way, they gave Anant guavas, warning him that they wouldn’t take him back home if he cried or didn’t eat them.

They stopped at the home of Pavan Pal’s relative, Ram Dayal, and spent the night there. The next day, 14 November, they set out for Etah, a town located 180 kilometres away, where they planned to spend the day at the home of Chhatrapal’s friend, Sunil Yadav. They had decided not to spend too much time in one place, and the next day 15 November, they paid a visit to Chhatrapal’s aunt, Santosh Singh, in Nagla Kashi, Mathura. They spent two days here.

Back in Noida, the Guptas were anxiously awaiting news about their son. It was 6 p.m. when they got a call on their landline. Nidhi answered the call nervously. The man on the other end of the line was abrupt. ‘We have your son. Once we get the money, he will be returned to you,’ he said before disconnecting the call.

Nidhi waited near the phone hoping for further instructions from the kidnappers. The second call came at 8.45 p.m., and this time, Nidhi asked the man to let her speak to her son. He refused, claiming the boy was unwell.

He once again demanded a ransom but this time was more specific. Nidhi would have to pay Rs 5 lakh in bundles of 500-rupee notes if she wanted to see her son alive again.

Nidhi, however, misheard the sum. She told the police that the kidnapper had demanded a Rs 50 lakh ransom for Anant. Over the next couple of days, the kidnapper telephoned the Guptas a few more times to discuss specifics of the ransom payment.

The police, meanwhile, began following the most obvious lead that they had, the mobile number from which the ransom calls were made. They quickly learnt that the kidnappers were from Noida. A scan of the call records from that number suggested that the kidnapping wasn’t the work of organized criminals or the result of a corporate rivalry, but rather the work of amateurs. This was both good and bad news. While amateurs would be easier to deal with, Rajesh said, their inexperience made it more likely that they would panic and kill the child.

Advertisement